Some people have been crucial in the development of their areas of knowledge over history. The industry was reinvented by Henry Ford; Albert Einstein opened new fields of physics; Ted Turner helped to create mass media.

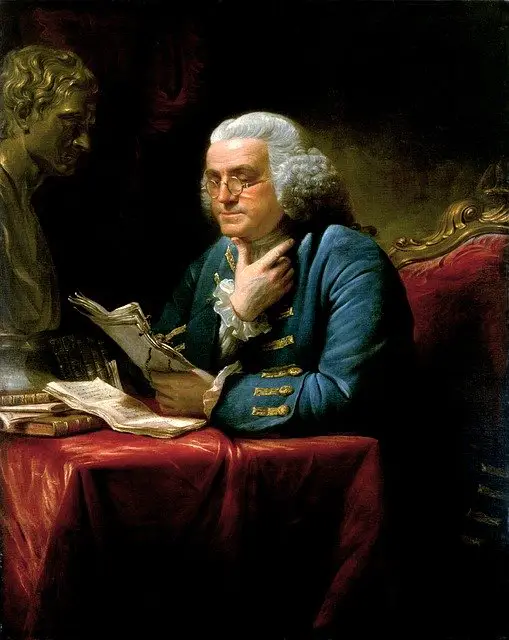

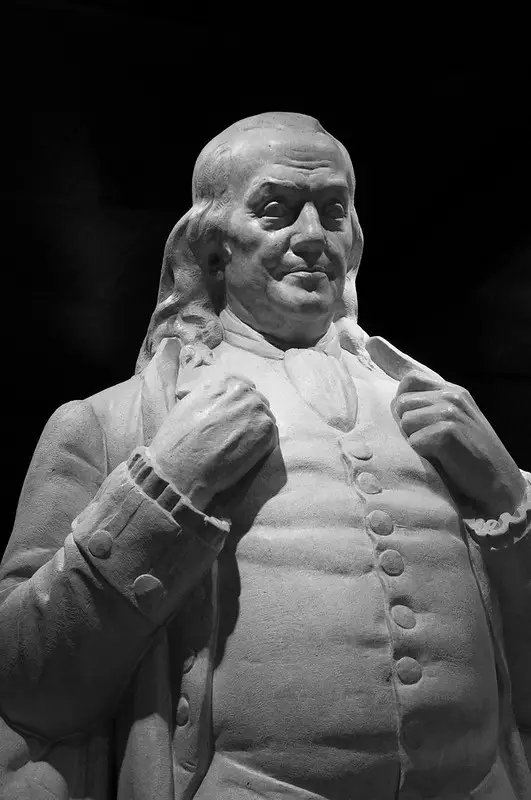

And still, there are so few people, who have reached and changed so many diverse disciplines and fields of research, like the American hero Benjamin Franklin.

Over his lengthy, famous life, with his initial observations about the existence of electricity, Franklin mesmerized the scientific society; he was an early innovator in the American printing industry; moreover, he was one of the key persons responsible for creating the political foundations of the United States.

This overview takes you through the impressive life of this man, from his initial years as a bright yet energetic kid to his eventual transformation into the most powerful politician in America. There is a lot that you will learn from such an inspirational person if you think of making an impression on the world.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks

Chapter 1 – Adolescent Benjamin Franklin, despite having had limited proper education, was outspoken and incredibly smart.

On January 17, 1705, Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston. Franklin has also displayed signs of individuality and creativeness as a young child, noticeable for instance in how he treated swimming.

Wanting to swim faster but noticing that his fingers and toes were stopping him from doing so, Franklin started to tweak the contraptions to help move him across the water more easily. His quick fix? Combining his hands with paddles and his feet with flippers!

His parents considered education for Franklin, and then for him to join the church. But Josiah, his father, quickly realized that his youngest son was not fit for the priesthood. There are several anecdotes discussing the mischievous ways of young Benjamin, and nobody depicts him as overly religious.

Franklin, for instance, felt that the prayer that his father chanted before every supper was boring. So after the meat was salted and packed in a barrel for that upcoming period, Franklin asked his father if he would instead say a prayer over the barrel, as it would be a time-saver!

Franklin was educated at a nearby school for just two years, where he was taught writing and mathematics. Then he got to work as an apprentice at just 10 years of age. First, he partnered with his father, and then with his older brother, James, who founded the first independent newspaper in Boston, the New England Courant.

Franklin gradually became weary of working with his brother, chopping over his assistant position as an apprentice – particularly when he had handled the paper on his own while James was away in England.

Thus, though still a teenager, Franklin opted instead to set out on his own.

Chapter 2 – The roamings of Benjamin Franklin brought him back and forth to London but his goal was to write above everything else.

He boarded a sailboat bound for Philadelphia in 1723 when Franklin was just 17 years old.

He got a job there with a publisher, Samuel Keimer, whom Franklin felt was “a strange fish,” but stuck with him because he liked their long intellectual debates. It was at this period that Franklin sharpened the debate skills that would later turn out to be so valuable in his life.

After being acquainted with Governor Sir William Keith of Pennsylvania, Franklin was given the chance to fly to London. He remained there working as an assistant to a publisher for nearly two years. Still, Franklin took the job and returned to America when a Quaker merchant offered him a job as a cashier in his convenience store back in Philadelphia.

Despite rising in the industry, his true love remained elsewhere – in literature.

Franklin realized he wanted to write and, while working at his brother’s printing business, he read constantly. He was greatly influenced by John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and the concepts of progress and self-development from the book stuck with him for the remainder of his life.

Another favorite book was the An Essay Upon Projects, by Daniel Defoe. Defoe’s book concluded that barring women from schooling and the rights which men openly enjoyed was cruel.

Franklin started regularly reading articles written in The Spectator, a British daily publication, often trying to improve himself and improve his writing ability. He would rewrite the essays he’d read in his own terms several days later, and then compare his writing to the first one.

The very first efforts of Franklin to compose were initially printed in the newspaper of his brother. Under the feminine pseudonym, Mrs. Silence Dogood, these satirical writings were published unnamed. Franklin’s early work demonstrated an extraordinary level of ingenuity for anyone of his generation!

Chapter 3 – Franklin’s theories about society and politics took shape after forming a network of like-minded people.

As a cashier, Franklin’s life was brief, and he quickly returned to his old work at the printing place of Samuel Keimer. Yet his increasing enthusiasm and determination could not be sated by anything.

Franklin established a club called the Leather Apron Club in 1727, later became known as the Junto. In comparison to older men’s clubs at the time, affiliates of Junto were aspiring business people and artisans who gathered to debate ongoing affairs.

The Junto turned into a stepping stone for many of Franklin’s community-development proposals, such as a subscription library, a levy on area constables, a voluntary fire department, and a school – which eventually became Pennsylvania University.

For the moment, Franklin’s views on politics and defense were controversial. He thought of a concept in 1747 to create a volunteer force, separate from the colonial government of Pennsylvania. Given the colony’s incompetent management of the threat from France and its Indian allies, he felt such a corps was needed.

Many citizens backed the effort – about 10,000 people signed up to enter the corps and wanted to appoint Franklin as their colonel even though he refused the role. Franklin subsequently wrote the slogan for the corps and designed insignia for its units. However, the corps dispersed in 1748, when the prospect of war had disappeared.

It is likely that Franklin did not know how controversial it was for a private group to take on the role of the state. The owner of the colony, Thomas Penn, did, however. He denounced the actions of Franklin as disrespect for the colonial government and pronounced Franklin a threatening man.

Of course, the true battle for dominance was only 20 years out. Meanwhile, Franklin wasn’t too obsessed about government issues yet – instead, he was focused on the world of nature.

Chapter 4 – The interest of Franklin led him to make important scientific explorations, especially with respect to electricity.

The Greek philosopher Plato said it was not worth pursuing the unquestioned life – and no one reflected this assertion more than Benjamin Franklin.

The irresistible interest that Franklin has would make him popular. Franklin witnessed a presentation during a visit to Boston in 1743 which included some tricks using electricity. Nobody at the time completely understood how electricity really worked.

Fascinated by what he witnessed at the show, Franklin began tests of his own. He soon noticed out there was a correlation between electricity and lightning, a phenomenon that was then regarded as mystical by most individuals.

He devised an experiment in which, during a thunderstorm, a person would keep an iron baton on a clear top of a hill with the intention of attracting a lightning strike – thus demonstrating not only that something made out of metal could attract an electrical charge, but also that lightning was actually electric.

In a message to the Royal Society in London, Franklin identified the pioneering experiment. Word spread quickly. A group of French scientists was able to reproduce Franklin’s experiment with success in May 1752.

In the meantime, Franklin wanted to do the experiment himself, using a metal key tied to a kite rope instead of a baton. Flying the kite in a hurricane, Franklin proved his hypothesis was right – lightning hit the key! He was then able to move the charge from the key to a special container called a Leyden container that held energy.

The development by Franklin contributed to the lightning rod invention. Yet his further discoveries into electricity received further praise; for instance, Franklin was the first one to name attached Leyden jars a “battery.”

But Franklin’s effort earned him disapproval and acclaim. His work was denounced as an insult to God by religious figures such as Abbé Nollet, while the German philosopher Immanuel Kant called him a “modern Prometheus,” having taken fire “from the gods.” But his career was on a rise. He has been honored with titular degrees both from Harvard and Yale.

Chapter 5 – An original proposal to bring together the American colonies was formulated by Franklin, but the time was not ideal yet.

Franklin turned his attention to the political sphere, after progress in science fields. But, as he would speedily discover, doing so was much more dangerous than lightning sparring.

Since 1747, when Franklin formed a volunteer militia, the issue of who was to fund the war against the French and native tribes has continued to intensify conflicts between the owners and inhabitants of the colonies.

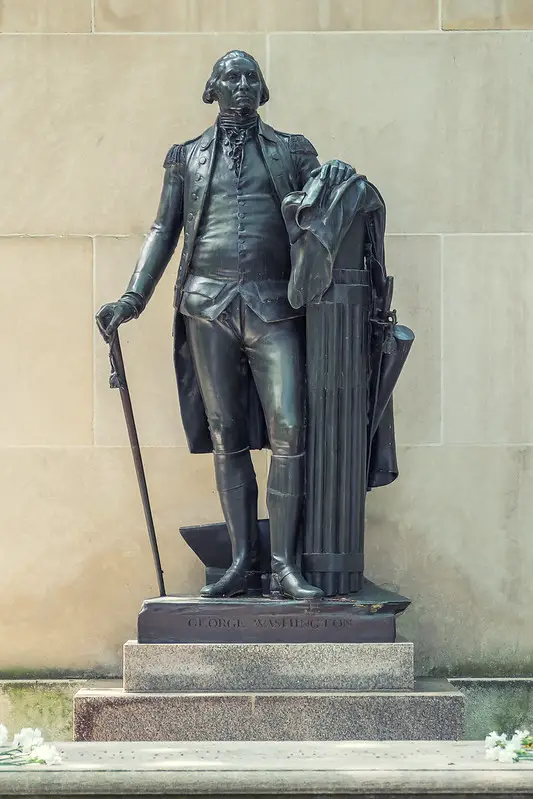

The British colonial government invited representatives from every colony to be a guest at a forum in Alban, New York after George Washington had been dispatched to the Ohio Valley in 1753 in a futile effort to expel the French from the region.

Franklin was now a vigorous foe of the colony owners and, together with the wealthy shipping merchant Thomas Hutchinson from Massachusetts, formulated a blueprint for a colonial union that he intended to propose in Albany.

Although the notion of imperial collaboration did not come up immediately. In a message to his friend James Parker from 1751, Franklin described how strange it was that six “savage” nations, talking about the Iroquois native peoples, could unify when a dozen English colonies could not.

Franklin’s proposal specified a national congress consisting of delegates chosen from each region, and ahead or “President General,” named by the king.

The proposal also described a new constitutional theory that was later to be called federalism. The “General Government” would rule on subjects such as the defense of the nation and growth to the West, while each colony would retain its own territorial governing authority and rule.

Franklin’s Albany proposal, however, was turned down; colonial assemblies argued it violated their authority.

In the words of Franklin, the proposal was “perceived to be very much of the democratic” as it was seen in England. While Franklin was suspicious of those who were in charge of the colonies, he also viewed the colonies of the United States as British. Yet this, too, will change quickly.

Chapter 6 – Franklin took the battle of the colonies to the coasts of Britain, but could not make the owners submit.

The Pennsylvania assembly addressed the issue again in 1757, three years after the Albany Conference and Franklin’s unsuccessful unity proposal.

It sent Franklin to London to express the problem with the big British families who had been given exclusive rights over the colonies, that is, possession. Failing this, he was to communicate straight with the British government. Franklin ended up in negotiation for five years.

In 1757 a series of meetings between Franklin and Pennsylvania’s owner, Thomas Penn, started. The main annoyance of the council was the desire of the owners to be excluded from taxation needed by the French and the native tribes to protect colonial property. This was considered by the council to be ‘unfair and barbaric.’

A jibe was inserted by Franklin in the legal charge. He failed to identify the Penn family as Pennsylvania’s “real and utter founders” – a small thing the Penn family didn’t like.

The topic of political influence then came up. The council had chosen a committee of administrators to meet with the native tribes, and Thomas Penn argued that he was within his rights to veto the resolution of the council.

Franklin protested, stating that in the 1701 Charter of Privileges, the former owner of the colony, Thomas Penn’s father William Penn, had granted the assembly precisely this authority. Thomas Penn aggressively cut off all contact with Franklin in retaliation, and it was a year before he actually replied to Franklin’s concerns.

Penn was unyielding in constitutional decision-making, claiming that the Pennsylvania assembly should only provide “advice and permission.” At this point, Franklin was persuaded that it was futile to attempt and charge the owners for the sake of the colonies.

Franklin made friendship with several leading British thinkers, especially the philosopher David Hume, after this failure, and discussed extensively on colonial topics. Franklin went back to America in 1762 and found that the political condition there had changed dramatically.

Chapter 7 – The final stroke for the colonies was the Stamp Act; Franklin felt the obligation for the British to leave.

Franklin was surprised back in Philadelphia by what he witnessed. Relationships have taken a severe shift for the worse between colonial residents and local tribes. The Paxton Boys were intimidating to come to Philadelphia and murder native Indians there, as well as any colonial citizens who were discovered hiding from them.

For Franklin it was clear that the colonial proprietary government would not be able to manage the crisis – so Franklin took off for London once again. He’d been gone for ten years this time.

In 1765, the British placed a levy on stamps to fund the war against the French and their native Indian allies, as Franklin had already set off. The “Stamp Act” would irreversibly shift the political viewpoint of both the colonies and Franklin.

The levy was really the final stroke for many colonial officials. A new generation of men, among them Thomas Jefferson, agreed that it was time to take the British away for good.

Members from 9 colonies came together to address the situation in October 1765. The discussion focused on unifying against the British imperial interests for the first time since the Albany meeting.

While the Stamp Act was initially sponsored by Franklin as a required, constructive measure, he soon realized how much colonial attitudes had shifted, and the reaction was intense against him. An angry crowd attacked Franklin’s house in Philadelphia, where his wife had barricaded herself alone, armed with a gun.

Franklin continued to hang on to the notion of colonial independence and quickly discovered that either the British Parliament had to extend all legislation to the colonies, or none. There was simply no place for agreement.

When Franklin eventually came back with his fresh viewpoint to Philadelphia in 1775 he was welcomed as a hero.

Chapter 8 – The discussion that led to the Declaration of Independence commenced with the essay of Franklin.

Franklin knew that if the colonists were to assert independence from British control they would have to rely on one another.

Franklin expressed his theories with the Continental Congress, an assembly of men advocating on behalf of the colonies against Britain, on July 21, 1775. The contents of Franklin’s draft of the “Confederation and Perpetual Union Articles” were closely examined and comprehensive.

The premise of Franklin was that a single-chamber congress would be created, with its members distributed proportionally depending on the population of each colony. Plus, Congress will designate a managerial council of 12 members rather than a single president.

Oddly, Franklin also stated that if Britain were to agree to the appeals of the colonists and capitalize restitution, the coalition would be disbanded. Franklin also regarded the conflict as an altercation, like many colonial officials, with individual British cabinet ministers and not with the Crown itself.

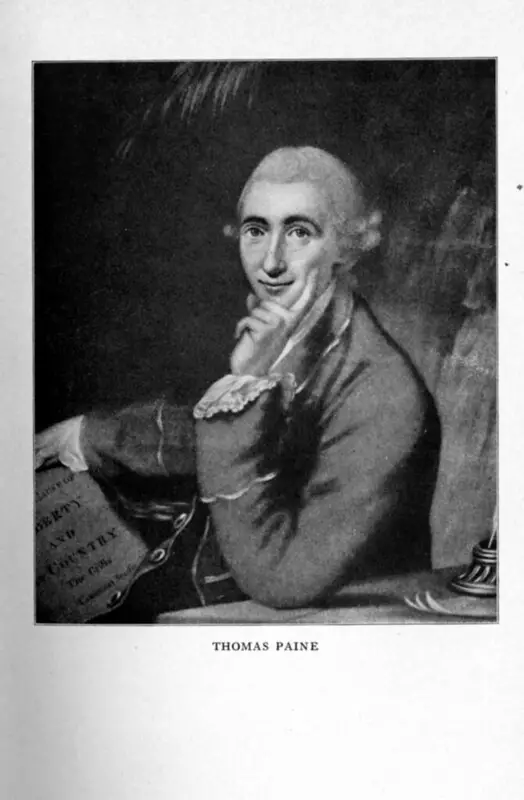

Yet a pamphlet was written in 1776 that would modify many minds and drive the colonies to war for independence.

Thomas Paine wrote Common Sense, while many at the time believed it had been written by Franklin. (Before publishing, Franklin had read it and recommended revisions to Paine.) Paine advocated strongly for the colonies’ complete freedom from Britain, focusing on the premise that there were no social or religious reasons for classifying citizens as rulers or subjects.

The pamphlet sold more than 120,000 copies – an unprecedented amount for that time – and it helped mobilize support for an imperial control movement.

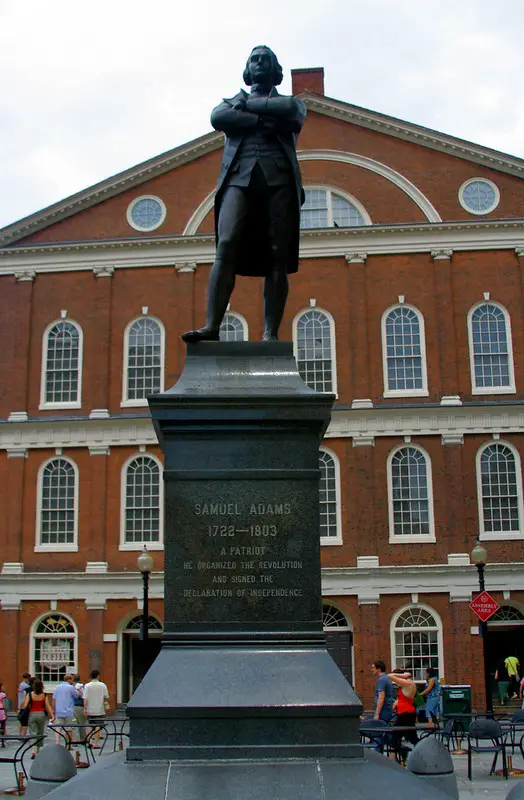

The Continental Congress voted for freedom on 4 July 1776. Although the declaration was ultimately published by Thomas Jefferson, Franklin proposed edits to the text, the most notable being modifying Jefferson’s “We hold these truths to be holy and conclusive,” to “We hold these truths to be self-evident.

This move demonstrates the impact on Franklin that humanist thinkers had at the moment. He claimed that human rights were not conferred on a few selected by God but were enjoyed equally in essence by all.

Chapter 9 – In establishing France as an ally in the American fight against Britain, Franklin played a crucial part.

Now, with their declaration of independence from Britain, America’s 13 colonies faced a very powerful opponent. The colonies will need an ally, namely the French, to have a possibility of victory in the war.

So who will be persuading the French to back their cause? Of course, Benjamin Franklin. The American Revolution’s progress still relied on him.

Franklin traveled to Paris in late 1776 to visit the French foreign minister, Comte de Vergennes.

He emphasized the precarious equilibrium of power between a newly independent America, Britain, and France in Franklin’s pitch to Vergennes – a matter he knew Vergennes would look favorably upon.

It would be a major loss for Britain if France were to help the Americans, who would lose all its American colonies and properties in the West Indies.

Franklin said that they agreed that the French should hold the islands in the West Indies if the Americans were triumphant. But if France pulled away from the cause, the Americans would have to satisfy the needs of Britain, which was, of course, in contrast with those of France.

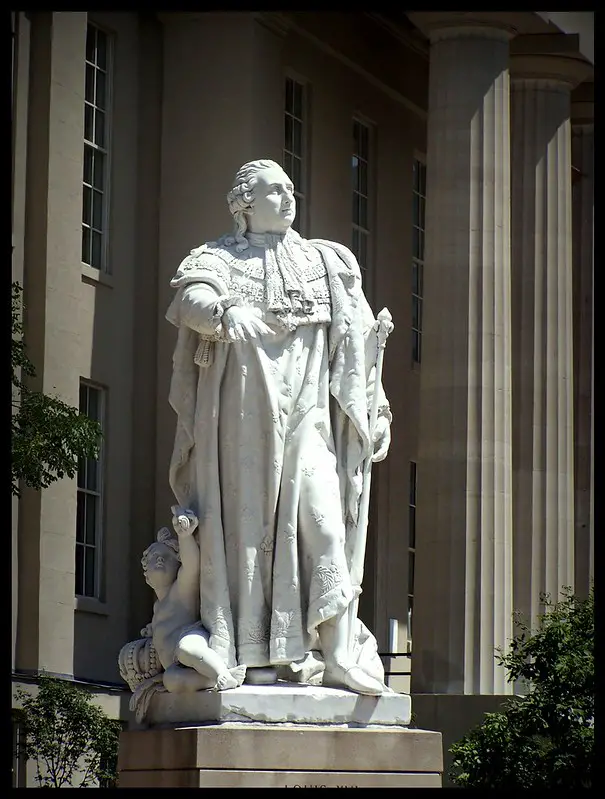

Vergennes finally promised to support the American cause, but the French procrastinated, and Louis XVI declared the coalition formal only in March 1778.

When this happened, thousands of people assembled outside the gates of the royal palace to see the iconic American, greeted with shouts of “Vive Franklin!” ” as his coach was pulling north. The coalition Franklin ended up achieving meant that the Americans had a chance to beat the British!

Chapter 10 – The skill of Franklin in negotiation benefited the young United States of America greatly after the Revolution.

It was time to fix up ties with Britain after the battle was over. Franklin’s calm and personality played a crucial part once again.

Franklin had placed himself as an isolationist early on in the war for democracy, claiming America should stop finding assistance from other nations. He later changed his stance, however, and believed that the States needed to be thankful for the assistance of France.

A disparity between Franklin and John Adams was created by this situation. Adams believed the French had committed to an alliance focused on national interests alone. America had not owed anything to France in his opinion.

Though, towards the end of the 1770s, the desperate need for funds for the war by America boosted the value of the alliance with France. The Americans couldn’t win without adequate financial support; and without an American battlefield victory, the British wouldn’t even consider treaties.

American forces continued to fight with France’s financial assistance, due to Franklin’s tactful diplomacy. In Yorktown, Virginia, British General Lord Cornwallis was defeated in 1781. This represented a triumph for independence and the start of the British peace negotiations.

Franklin faced a dilemma as one of five peace representatives after the war was over. America had already agreed with the French to arrange negotiations, but the British leaders decided to communicate with the Americans individually.

Franklin played a dangerous game in the following months by communicating with British leaders without letting the French know. He recommended to the British in those meetings that they transfer control of Canada to America, recognizing that this was something France did not want, since it would make America stronger and less reliant on France.

The sides concluded a peace treaty on November 30, 1782, whose opening words proclaimed America to be “free, sovereign, and independent.” The French were angered by this declaration.

But the excellent negotiating qualities of Franklin come into action once again. He not only soothed but persuaded Vergennes of the current autonomous direction of America.

Chapter 11 – Franklin left an unerasable impression on history, as a co-author of the American constitution and a civil leader.

The money was so tight in the treasury as the news of the British defeat reached Congress in 1781, that congressional representatives had to pay the courier out of their own pockets.

Congress had very little functional powers, as laid out in the Articles of Confederation, and did not levy taxes. There was a desire for democratic reform now that the war was over.

With the Constitutional Convention, of which Franklin was a key figure, the reform came in 1787.

A main topic during the conference was how to represent US states in Congress. Franklin observed that, with proportional representation, smaller states were afraid of losing their freedom; with an equivalent amount of ballots, bigger states worried that their resources would be at stake.

Franklin requested that the gap be divided. Congress would contain a lower house, for which delegates would be chosen on a proportionate basis, and an upper house, for which an equivalent number of senators would be named from each state.

Taxes and expenditures would be controlled by the lower house (House of Representatives); executive officials would be approved and all questions of jurisdiction would be dealt with by the upper house (Senate). Finally, Franklin’s suggestion was approved.

But there was no halting Franklin’s mission. His last assignment in life was to try to abolish slavery.

In 1760 about 10 percent of the citizens of Philadelphia were slaves. Over the years, Franklin’s thoughts on slavery had grown such that he was firmly abolitionist by 1787 and became the secretary of the Pennsylvania Society to Promote the Abolition of Slavery.

Franklin sent a letter to Congress in 1790, which stated that its duty was to preserve equality for the American people “without distinction of color.”

But, amid Franklin’s attempts, those who were in favor of slavery opposed the petition; they claimed that it was explicitly approved by the Bible.

Benjamin Franklin died at the age of 84 on 17 April 1790. Franklin made an everlasting impression on American history from his early curious years through to his renowned career as a statesman. More than 20,000 people participated in his funeral ceremony, to commemorate the great American.

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life by Walter Isaacson Book Review

Benjamin Franklin’s life reveals how one person can change the trajectory of history through his infinite imagination and caring involvement in human development and freedom.