What do you think when you imagine Hawaii? Most of us envision heaven of shores of volcanic sand, stunning mountainscapes of the forest, and softly swinging palm trees. These are the sights that have drawn tourists for the past eight hundred years, from the early Polynesian explorers to your Aunt Helen, who last season went on a trip there. Maybe your aunt doesn’t know very much about the background of Hawaii, but she isn’t the only one. Up until very recently, even historians knew almost nothing about Hawaii’s history. That’s because Hawaii had no written language until it was absorbed in the early nineteenth century into the global marketplace.

Yet there is something we can study from its centuries of background. For instance, the geological documentation can be questioned and contrasted with the mo’olelo, Hawaiian folk tales, and stories handed down verbally for centuries. As a result, we can obtain a fresh understanding of how what it now comes to be this special Pacific culture. But only if we understand economics can we completely comprehend this past. In this island heavens tale, wealth, commerce, and compensation politics have played an enormous, unpredictable part.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks

Chapter 1 – When Hawaii was first inhabited by people, it gave them a rural, culturally inclusive heaven.

The last big area of land on earth to be inhabited was Hawaii. Twelfth-century Polynesian explorers, who had migrated about two thousand miles in pursuit of new territory, became the first people to reside there.

In the eighteenth century, Captain James Cook was the first European to lay his sights on the islands. He believed that the Polynesians had come to Hawaii because their canoes had been swept off the route by the storm. But later study has shown this to be highly improbable scientifically. Such expeditions were deliberate.

Then why did Polynesian small groups plan to abandon their homes in canoes and head out for the next world? Maybe they were motivated by the opportunity to explore, or maybe they wished to pursue options they didn’t have at home.

It is, of course, dangerous to head out for a journey of thousands of miles in an outrigger canoe. In the open sea, all kinds of things could occur, or you could simply run out of resources. Yet for over three centuries, Polynesians have been wandering like this. They learned to mitigate the dangers.

They examined the planets, the sun, the ocean, the waves, and the marine animals to plot a route. They were bearing sturdy cream of breadfruit and a single giant taro root that would survive for months. A properly built canoe will be able to move about 100 miles a day.

At the moment, no one resided on the islands, so occupying them was easy. For one thing, Polynesians didn’t have to deal with aboriginal people’s backlash. The settlers also committed their efforts to the implementation of irrigation as well as other structures. They constructed canoes for fishing, made fish hooks, and established enormous communities, as we’ll discover in the upcoming section.

Economic background tells us that, huge land endowments are normal when land is mildly populated. The islands of O’ahu and Kaua’i are convenient for cultivation, with their rain-fed, covered valleys. So, with elaborate irrigation technologies borrowed from Polynesia, the inhabitants established massive taro fields. Everybody was working for themselves, for the majority of the time, and there was no major difference in income.

Historians agree that throughout the first century or so of colonization, Hawaii’s original inhabitants had an inclusive culture. There was more than enough of an agricultural field for everybody, so there was no need to fight with each other at all.

Chapter 2 – The initial population increase rendered the social structure of Hawaii more complicated.

We don’t know if the Polynesians were the greatest farmers on the planet, or if the soil was simply extremely nice. What we can tell is that the taro farms of Hawaii in the thirteenth century created immense agricultural excesses; those excesses were larger than those created by American farmers as late as the nineteenth century. But the prosperous days did not last; certain lasting improvements in the Hawaiian socioeconomic order was created by excesses.

Firstly, an extremely high population increase happened. Academics report that women have given birth to four children on average, based on the approximate settlement date and Hawaii’s current population. Despite heatwaves, tsunamis, floods, earthquakes, and even throughout the conflicts that would become a daily event, the colonists kept this going. It is believed that these fertility rates would be some of the largest ever.

Two classes have arisen in the increasing population: the elites, known as the ali’i, and the farmworkers, known as the maka’āinana. The variations between the ali’i and the maka’āinana were not very significant at first. The elites had to offer resources for the workforce to stick with them because there was more soil than labor.

Thus, as long as vacant land of top quality was accessible, the community remained largely egalitarian. The workforce could just migrate to the next abundant field or another island if they felt robbed by the elites. But Hawaii sold out of vacant land in the fifteenth century. Now, further power over their subjects may be exerted by crafty chiefs. A confusing constitutional order evolved.

Mandated taxation and consolidated authority were among the new democratic regimes. Such approaches have expanded from island to island. Ali’i from the Hawai’i and Maui Islands paid a visit to the governor of O’ahu Island during the fifteenth century, where Honolulu is now. They were afraid of the resources that they had. They were presumably trying to imitate his system on their islands.

The situation on O’ahu Island was a significant breaking point. In the chaos, a single leader, Haka, conquered another island and came to rule the whole island of O’ahu. To solidify his control, he delegated ali’i and maka’āinana to separate divisions of territory.

Even though there was no personal land, these land allocations were significant. To boost his influence, it was the first time a Hawaiian chief had reallocated land; it wouldn’t be the final.

Chapter 3 – Hawaii’s politics and culture were rapidly changed by the first encounter of Europeans and Native Hawaiians.

The white-sailed ships of Captain Cook landed off the shore of the island of Kaua’i in 1778. Everything was bound to transform forever in Hawaii.

Three following incidents were crucial to Hawaii’s future. First, a market launch. Second, a significant decrease in the number of Native Hawaiians. Finally, under King Kamehameha I, the more accumulation of authority. Eventually, these occurrences lead to shifts in socioeconomic systems and the Māhele, a massive transfer of land that for the first time would establish property rights in Hawaii.

Further unification of political power was the first significant reform that occurred from the alleged “discovery” of Hawaii by Cook. On the island of Hawaii, Kamehameha I, the ruling leader, collaborated with Europeans to procure firearms, cannons, and Western ships. He secured his power over six of the eight main islands in this manner.

A resource increase was one significant modification. China wanted tons of sandalwood oil, which was harvested from trees on the abundant islands. A whaling boom soon preceded the sandalwood boom. They needed workers for these new factories, so people started to migrate to towns. The job market that was historically focused on agriculture was hindered.

A significant demographic loss has intensified the rural population decline. The Europeans carried bacteria, as with many initial encounters between individuals from the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. This ended in a disastrous amount of lives lost. Between 1778 and 1831, unnatural deaths killed as many as 75 to 80 percent of the Native Hawaiian people.

The conventional distinction between the ali’i – the agricultural owners – and the peasant maka’āinana community was weakened by the demographic decline. Native Hawaiians started migrating to the new cities of Honolulu, Lahaina, and Hilo in search of jobs and Western consumer goods. They left the ali’i with vacant farmland and no revenue.

Hawaiians have become less related to their land. Around the same time, outsiders stared at what they considered as valuable vacant land hungrily. The Māhele was authorized by King Kamehameha III in 1848 to resolve this new truth.

A major restructuring of land rights was the Māhele. Between the empire, the ali’i, and the maka’āinana it divided land. This laid the foundation for the problems that would tend to define political and economic life in the twentieth century: the dispossession of Native Hawaiians and the domination of Big Sugar.

Chapter 4 – The Māhele laid the foundations for Big Sugar’s ultimate domination.

The ruler, the ali’i, and the maka’āinana could now possess their land, in the European sense, with the creation of the Māhele. In return for a label, all the ali’i and the maka’āinana had to do was file an official statement. But this was not achieved by any of the lower-class maka’āinana, possibly because there was no correspondence, but also because the notion of land was also a completely new thing. Most of the land allotted to the maka’āinana eventually went uncollected. Then the state sold it.

On the other hand, the ali’i not only demanded their land but used it quickly to obtain access to a lucrative new world market: sugar. And the increasing trade in sugar would ultimately lead to the invasion of Hawaii by America.

Many ali’i rented or sold their fields to enterprising Americans and Europeans who knew Hawaii’s rich soil’s sugar-growing capacity. These initial sugar plantations were the most frequently state-licensed collaborations between international investors and owners of ali’i.

Growing international sugarcane investment could challenge the independence of Hawaii. There was also a low risk that the new plantations would become so financially powerful that, for now, political interference could be applied. In the meantime, Hawaii and the United States have been getting pretty close politically. Commerce between the two nations grew quickly; over half of Hawaii’s exports went to the United States by 1850.

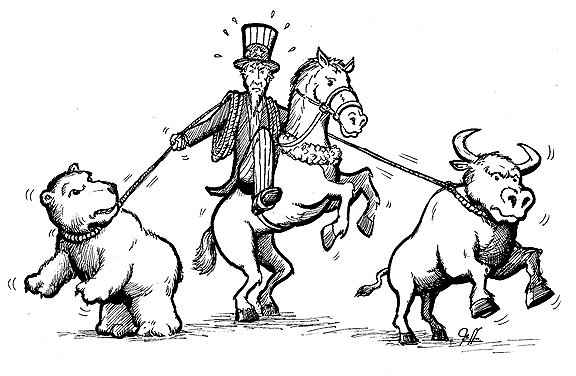

A free trade treaty was adopted in 1876 by the US Congress. For both Hawaiian sugar farmers and their American customers, this was meant to ease out commerce. Yet evidence reveals that the United States is potentially losing cash on the contract. The agreement seems to have been more about the United States holding Hawaii under its influence than making commerce affordable. In fact, President Tyler had proclaimed Hawaii part of the formal zone of power of the United States back in 1842. Today, rumors of annexation have gotten stronger and stronger.

For the sugar corporations known as the” Big Five”, this new deal induced tremendous development in the 1880s. Hawaiian sugar shipments to the United States grew from 21 million pounds in 1876 to over 220 million pounds in 1890. Over thousands of Chinese and Japanese workforce were also brought on indented contracts for the sugar fields. Jobs in farms grew from just under 4,000 in 1872 to over 20,000 in 1892.

The Ali’i and the King had decided that to manipulate Hawaiian affairs, sugar would not become strong enough. They’ve been mistaken.

Chapter 5 – To undermine the Hawaiian empire, the US government and sugar tycoons worked together.

The negotiating role of the Hawaiian king deteriorated as the sugar lobby expanded. So the US government sought to obtain more ideal conditions when it came time to renegotiate the free trade deal in 1883. This succeeded. King Kalākaua had offered the US government a new prerogative when the treaty was renewed again: an American military base at Pearl Harbor.

At the very same period, with the Hawaiian administration, the sugar tycoons were becoming extremely dissatisfied. They needed higher capital investment to help the production of sugar. The role of the king appeared far more unstable.

In 1887, the crisis reached a climax. King Kalākaua was captured at gunpoint by government enemies, including a small army of white individuals. They pressured him to approve a new council and issue a new regulation, weakening the control of the king seriously. The new constitution came to be known as the Constitution of the Bayonet. It presented the empire with a strike that eventually proved lethal.

The United States passed another customs duty pact in 1890 to further weaken the Hawaiian empire. The freedoms Hawaiian sugar industries had cherished were abruptly gone.

Hawaii has sunk into an economic crisis as a result. In one day, sugar prices dropped 38 percent. Today, the sugar farmers in Hawaii have a new objective: to merge Hawaii into the United States. They’d have lower-cost access to US consumers that way.

In 1893, a team of influential white citizens toppled Queen Lili’uokalani with the help of the US delegate to Hawaii. The USS Boston forces landed to “protect American lives and property.” Lili’uokalani surrendered the crown against her own free will.

Hawaii formally became a United States territory in 1900. The US Congress, with no support from the Hawaiian people, made the announcement. The US government dispossessed all of the territories of Queen Lili’uokalani as part of the agreement, about 24 percent of the total land of Hawaii. She didn’t get any reimbursement.

Clearly, the US government was the major winner in the colonization process. It relocated rapidly to create a network of army bases in the Pacific to reflect its strength. Sugar plantations have also had immense advantages; their political impact has strengthened and their land rights have become more protected.

Local Hawaiians, on the other hand, have come up short. The Hawaiians were stuck with less wealth than their own when the kingdom lost its territory and authority was shifted to Washington.

Chapter 6 – The Big Five continued to control the islands even as Hawaiians won democratic privileges.

The Hawaiian Organic Act was passed by the US Congress in 1900. This created a regional government and granted Hawaii residents U.S. citizenship, including Native Hawaiians, the majority of white people, and Hawaiian-born children of Asians. They were eligible to join political and social organizations, print journals, and set up schools. In the end, people unhappy with the existing order had the means to advocate for reform.

Moreover, the Act created a two-house legislature put in office by men over the age of 21 who were able to read Hawaiian or English.

The state of Hawaii was not autonomous; Congress could at any point change the Organic Act. And within Hawaii, there were no city councils, which made it simpler for the US government to track regional authorities.

Besides, the sugar and pineapple farms served as a form of regional authority in essence. They offer their staff medical treatment, lodging, accommodation, and other facilities. Yet there was no actual leverage for workers to reform the political structure.

The legislation was largely in the interests of the Big Five during this time. Countrified areas were, for one aspect, well served in the parliament, but little Hawaiian people were residing there. Asian farmworkers who were denied from nationality by discriminatory naturalization laws became the majority of rural inhabitants. So, white plantation owners and farmers were the key electors in rural counties. A ton of importance was borne by their ballots. In the meantime, with Hawaiian natives who were US citizens, cities soared, but the portion of those regions in the parliament did not rise.

So, white voters dominated the politics of Hawaii. By incentives given to the Big Five companies, they were paid for their elections, as many white people just so happened to be working as professional employees, supervisors, and proprietors.

A strong elite has formed. The board members of the Big Five came to control the same interest groups, neighborhoods, and even households. Besides controlling transport, retail, and banking, these organizations dominated the sugar and pineapple economic sectors.

But the constitutional order of Hawaii was about to change, forever.

Chapter 7 – Most of its citizens got better to reach the political structure when Hawaii became a state.

Throughout much of the colonial period, statehood for Hawaii was a popular issue. But it scared Legislative leaders, mostly white senators from the Jim Crow-era South. In Washington, they dreaded the specter of “Mao-suited Chinese representatives,” supposedly “communist” trade unions, and the effect Hawaiian lawmakers may have on the pending discussion on human rights.

For years, since it wouldn’t change their result, the Big Five were resistant to statehood. Why deal with a mess like that if there wasn’t too much to benefit?

But in 1934, when Congress prohibited immigration for the Filipino workers they depended on, Hawaii’s sugar planters observed desperately. Another strike came when Congress passed a customs tax law that favored the growers of homeland cane and beet sugar over their equivalents in Hawaii. It became obvious that Hawaiian sugar farmers would never be on secure ground in the American sector until Hawaii was included in the US Congress.

Statehood supporters had to deal with skepticism from Congress. Because they wanted to show forthrightly that the people of Hawaii were willing to accept the duties of governance. To be accepted by Congress and the president, pioneering legislators appointed a constitutional convention to draft a highly praised state constitution.

Moreover, Hawaii had obtained a strong new ally: the Republican national party. Republicans controlled Hawaii at the time, and so statehood would improve their Congressional stronghold. Eventually, Hawaii became the 50th US state in 1959.

Hawaii is estimated to account for 2 percent of the Senate in a single stroke, from fewer than 1 percent of the American population. The first Asian-American to be voted to the US Congress was Hawaiian Daniel Inouye, a Japanese-American hero of World War II. In the Senate, he continued to serve nine terms, shaping laws to represent the needs of Hawaii and having greater access to federal stimulus programs.

In certain aspects, statehood changed Hawaii from an elite-dominated colonial community to a wealthy, thriving democratic country. But this came at a cost: the loss of independence by Native Hawaiians was never discussed adequately. Neither was the expropriation of Queen Lili’uokalani ‘s crown estate.

Chapter 8 – Electors exercised their new authority after statehood to divide territory more evenly.

Native Hawaiians held off behind all other ethnic groups in jobs, schooling, and cultural life in the twentieth century. For them, the imperial period was a tragedy. Statehood hasn’t fixed that. Another issue was also not addressed: the overwhelming amount of Native Hawaiians and Hawaiians of the lower classes did not expect to afford to purchase land in their lifespan.

In the United States, outside of Hawaii, the proprietor of a house nearly invariably owns the property on which it sits, too.

Instead of selling the property, several large estates in Hawaii switched to leasing activities. That’s because purchases, dependent on years of possession, may have caused massive federal tax obligations. 26 percent of residential property was rented by 1967. 68 percent of these contracts were given by three major landlords.

Property owners treated large leasing arrangements as a legacy of the colonial era in a fairway. These arrangements were designed to assign taxes to companies, landlords, and the state.

There have been some efforts to allocate land to native Hawaiians. The Hawaiian Homes Commission, an old project, is generally viewed as a failure; much of the land in question ends up in government possession.

When all the people of Hawaii became residents, they campaigned in 1967 to adopt the even more effective Land Reform Act or the LRA. Via the LRA, major landlords will be obliged to sell the property to people who owned houses on that property at a judicially prescribed amount. The financial influence of the Big Five and supporters of the Republican alliance would be limited by this. The LRA would also ensure leaseholders with economic incentives, allowing them the opportunity to purchase the property when they are ready.

More than 23,000 homeowners acquired the property under their houses, beginning in 1991, following litigation that went all the way to the US Supreme Court. Yet many problems still exist.

Some claim that the LRA’s main aim could not have simply been to regulate the big landowners’ market force. Instead, it largely helped to improve Hawaii’s citizens’ role in the democratic political layout.

For example, land reform has not necessarily lowered land prices. Yet it accomplished a more equitable arrangement with its fair transfer of land. With more citizens buying land, they have an opportunity to promote legislation and regulations to promote property rights. This increased the prosperity of the new political system.

This was just one more way for the old imperial system to brush out its remains.

Hawai’i: Eight Hundred Years of Political and Economic Change (Markets and Governments in Economic History) by Sumner La Croix Book Review

Hawaii’s journey is one that we can only fully grasp by researching the economic factors that created it. In the past of this island heaven, wealth, exchange, and resettlement have played an enormous, unforeseen part, from the early days of taro farming transported from Polynesia to the soaring heights of the Big Five sugar planters, to the continuing fight for Native Hawaiians to gain their equal share of expropriated property.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks