As all of us are cognizant of them, there are subjects of conversation that may result in a heated debate due to people siding with two rigid views: Who do you cast a ballot for, and what is the reason for voting that person? Do you think people should be allowed to get an abortion or not? Does God exist? Or instead of one, are there several gods? Or is there no God at all?

How we respond to these important questions and what we think politically, morally, and with regard to religion shape our identities. So, it is not surprising that there is a sense of upset arising in us when we encounter a person not thinking in the same way as we do. The decision may be difficult to make: are we going to fight for what we stand for, or will we let it slide and tense, irritating silence fill the atmosphere?

However, the decisions you must make don’t need to be limited to two avenues. You can talk about emotive and contentious matters without fists taking action. How would it be if we prepared our indisputable facts and numbers and began talking with people rather than talking at them? How would it be if we were considerate of the questions we direct at people and truly paid heed to their responses, rather than trying to alter their views by use of sheer force? How would it be if we instead attempted to assist people to question their views?

The writers of the book, Peter Boghossian and David Lindsay discuss that such an attitude would be much more efficient – and people would be closer. You’ll learn how to adopt this attitude via this summary.

Chapter 1 – It is possible to convert ”impossible” conversations into an efficient one by working together on that.

Our views play an important role in our lives. However insignificant or important they can be, they influence how people act. Is it freezing? Then we put on a jacket. What is the reason? Your opinion is that the jacket will protect you from coldness. There are other views that can have more solemn ramifications. Voters who believe that the citizens of their country are dying in the hands of immigrants, for instance, may cast their ballot for a leader who swears to take any action that’ll preserve the safety of his citizens.

As the importance of a topic increases, so does the possibility of you coming to blows with people whose beliefs are in contrast with those of yours. When either of you assumes that what you believe is correct, then it isn’t probable to have a smooth conversation. However, you can actually hold fruitful conversations regarding polarizing topics.

Let’s define the ”impossible conversation. It is a type of discussion that is believed to be had in vain – a discussion where the difference between opinions, assumptions, and worldviews seems to be impossible to eliminate.

A vital factor that is usually absent in these conversations is give-and-take. Instead of talking with each other, you alternately talk at each other. None of you actually hears what the other side says. Rather, you just bombard your opponent with what you believe is right, or graver, you get into an altercation.

However, it is good news when a person wants to converse, as it is likely to possibly hold a fruitful discussion. Ideas aren’t rigid and we can change them, however, we can either do it in a bad way or a good one.

Putting pressure on someone is the wrong approach to alter another person’s beliefs. Leaving aside its unethical side, we can just reject this on the basis of one reason: it isn’t functional. There is no person who has genuinely reconsidered their views upon being hit in the face. You might hear them saying that their opinions have transformed, however, it is nothing but a fake statement usually.

But, many people’s views have undergone a transformation after having a conversation.

The reason for this stems from the collaborative aspect of conversations. When you manage to perceive things in a different way, it results partially from the fact that you produced the views that assisted you to alter your way of thinking. Therefore, one reason why people end up reconsidering their views is conversations, this feature of which we will discuss in the following chapters

If you collaborate with another person, the outcome will be more favorable than if you just speak at them that their beliefs are incorrect and, most likely, foolish as well.

Do you think this is very Heidi-view in an age divided and polarized? No need to fret about it – in the subsequent chapters, you’ll see concrete methods to assist you to have these sorts of discussions!

Chapter 2 – Do you aim to alter the beliefs of another person? Then you need to pay attention to their words.

Think about a dancer putting on a series of pirouette on the stage, or a surgeon performing a dexterous incision using her scalpel. Their actions are quite intricate, however, it is based on simple foundations. Should dancers and surgeons not grasp the fundamentals of their professions, neither ballets nor operations could be probable. The same thing goes for productive conversations as well. The conversation is an ability, and if you want to hone it, you need to start with its basics. What is the way of doing it?

Rather than listening, first, let’s examine the other facet of the equation, which is ”talking”. What is the reason for people not caring about arguments that are forcefully persuasive? This has a rather easy answer: people don’t take kindly when we argue as if we are lecturing them.

Lecturing another person resembles conveying a note. After having uttered what you wanted to say, you’ve got no business left; people that listen to you have to decide to agree or disagree with the message. It is very functional in some cases – such as in lecture halls – however, this may rebound in conversations had by people who are equals.

However, one other cause of lectures being unproductive also exists. Let’s examine some research done in the first years of the 1940s by psychologist Kurt Lewin.

The US government employed Lewin to convince housewives to use internal organs of animals more often. What they were anticipating is this would be helpful in mitigating the lack of meat during the WW II.

Lewin experimented with two strategies on two groups of women. He lectured the first group and provided a lot of facts about the war effort. He directed this question at the second group: According to them, what is the reason for this policy to be sensible.

Merely three-hundredth of women from the first group decided to change their behavior. As for the second group, this figure was almost forty-hundredth of women. What was the outcome of this experiment according to Lewing? It is more probable that people will hold true ideas that are the product of their own minds rather than ones given to them by others.

Now, we can move on to listening. What’s the way of realizing that you actually lecture people rather than having a conversation? You can understand it by asking this question, “Did the person ask me to share this?” Is your response negative? Then, what you’re doing is most probably lecturing, which indicates now’s a good time to adopt a different approach.

Consider the events you’ve gone through. Which people would you prefer to invite to dinner: The authoritative person who has an opinion about everything and who acts like you are his pupil? Or the person posing questions to you and paying heed to your words? Well, there is no need to think much about it, is it?

Don’t forget, it is a nice thing that people know others pay attention to what they say. Let these psychological insights be the foundations of your conversations, and it’ll benefit you a lot.

Chapter 3 – If there is harmony between people having a conversation, people can discuss their opinions candidly and point out to the things they disagree with

What follows after falling into a dispute with our friends? For much of the time, people ignore their differences, don’t they? Well, friendship matters a lot more than making rhetorical points or triumphing in discussions. However, naturally, there is no way one can befriend every person. However, there is something we can deduce from friendship with regard to the talent of having fruitful conversations.

Psychologists say that between friends, rapport builds up. Rapport refers to the feeling of being relaxed and being on good terms with others, of putting confidence in them and their motivations. Rapport is the explanation as to why friendships are able to endure when there are conflicts stemming from differences in opinions.

Think about two friends getting along very well with each other but having completely conflicting opinions about a topic. The friends will most likely think that each has good reasons for being so attached to their opinions. Accordingly, the friends will show more tolerance to advice and lower their defenses.

This doesn’t mean that it is better to think of strangers as if they were friends and to try to establish a great level of harmony with people you are unfamiliar with. However, it is possible to build some rapport before talking about other topics. “Street epistemologists” apply this tactic each day.

It is possible to see street epistemologists talk about contentious topics – such as whether there is a God or not – with people they are totally unfamiliar with. As we can deduce from their name, they talk about such subjects on the street, and the technique employed by them was created by ancient Greek philosophers. For them, a conversation is a way of assisting people to reconsider their views. The sole thing that assists them to do it and not to hurt other people’s feelings is to build rapport.

It is possible to make a valuable deduction from conversations like these. Initially, you should get closer by posing general questions regarding names, professions, etc. Your goal is to detect a point of intersection. Possibly, you’ll notice you share a lot of things with this person. Perhaps you’re both going to be parents, or you dwell in the same apartment. Remember these things that you both share if the conversation turns into a heated debate, and you’ll never forget that the person you’re talking to isn’t an enemy of your mind’s creation but a person very similar to you.

One other thing you should adopt is to stay away from the parallel talk. The parallel talk means that, for example, your conversation partner starts talking about his holiday in Cuba, and you see it as a signal to begin recounting your days in Cuba. Posing questions to your conversation partner about their vacation is a straightforward and efficient method to build rapport. However, taking advantage of their stories to share your experiences, on the contrary, is a perfect way to impair this rapport!

Chapter 4 – In order to alter the beliefs of another person, you have to initially present them something that’ll make them dubious of their beliefs.

Could you tell us the way a toilet functions? Two psychologists posed this question as part of one research published in Cognitive Science. They asked participants to give a number of their level of understanding of the way a toilet works. The participants had to answer this question twice – The first time was before they told researchers the way a toilet functions and the second time was after talking about it.

What was the outcome? Many participants began talking about their knowledge about toilets rather assuredly, however, they had in fact no idea with regard to fill valves and overflow pipes.

Such a misconception that is done by many people is a sign for us to understand the way that can make people reassess their views.

According to what philosopher Robert Wilson proposes, we usually exaggerate our knowledge about the world since we put faith in the knowledge of other people. We can make an analogy to taking books from the library to return later; however, they remain on the table with no one reading them. Then people believe they’ve absorbed all the information – these unread books could offer.

This effect that is known as the unread library effect has repercussions in reality outside. Take, for instance, one research from 2013 published in Psychological Science. The researchers discovered that political extremism in the United States had very close links to a misconception of understanding. As research has shown, people were talking in a very extremist way about policies – despite the fact that they didn’t seem to know actually anything about these policies.

You can take advantage of this knowledge and use it your discussions. Do you remember that we told you to keep in mind that giving a lecture about something to people is not as productive as asking them to make up their own opinions? So, should you want to alter another person’s opinions, they should be the ones that make up their own doubts as well.

Initially, you have to apply something called modeling ignorance. Should you want a person to realize the boundaries of their information, act as if you were ignorant. Ask them to explain things. Posing open questions to people works perfectly. First, utter a sentence like this, for instance, “I’ve no clue as to the way these mass expulsions of illicit immigrants would affect things.” Let them respond to you, and later start asking other questions. Be bold while doing this. Go deeper and ask more fundamental questions with regard to the topic, and keep pretending as if you were ignorant.

Where will this wind up eventually? There are two possibilities: First is that that person will understand that his knowledge is actually limited. Second is that you find out he actually knows a lot about the topic, you get the chance to learn a valuable lesson from that person.

Chapter 5 – So as to develop reciprocal respect and openness while arguing, apply “Rapoport’s Rules.”

When you are miscomprehended, it is very annoying, isn’t it? What’s especially worse is when people misunderstand you on purpose. After someone miscomprehends what you say intentionally, what your genuine opinions are is insignificant now. Rather, that person fights against a straw man – a deliberate misunderstanding far simpler to overcome than what you actually think. Not only does it render conversations fruitless, but it engenders profound unfairness as well. Fortunately, it is possible to avoid such things.

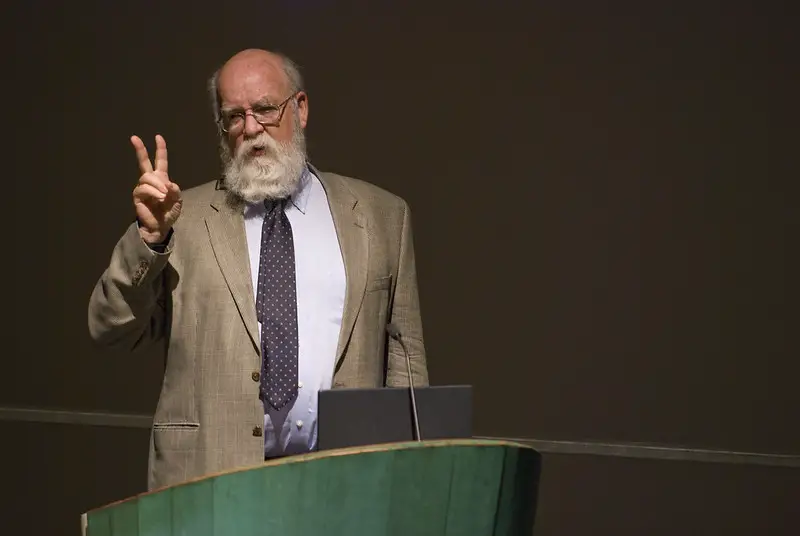

What’s the way of not turning into a barbarian while censuring someone? the American game theorist Anatol Rapoport made efforts to come up with a response to this question. Rapoport created a checklist for saying aloud points on which people cannot agree, which is known as Rapoport’s Rules. The four rules set by Rapoport were organized by Daniel C. Dennett, a philosopher who viewed them as the “best remedy” to the inclination to restate other people’s remarks.

Then, how do they function? Let’s take a look at the list, in sequence.

According to the first rule, you have to try to restate your partner’s position, using your own terms. Your rephrase should be as transparent and just as possible because the reaction you would like to hear should be “wow, I would like to explain it as well as you did.”

According to the second rule, you should write down on whichever points you and your conversation partner share the same view.

According to the third rule, you should explain to the person you’re having a conversation with the insights you gained from their point.

Ultimately, according to the fourth rule, you should express the points you are in discord with once you’ve employed the first three rules.

There is a precise explanation behind each of these rules. The first rule, for example. Restating your partner’s point shows you try to grasp their approach to the topic. Going through the points about which you share the same opinions, as required in the second rule, forms an impartial area where both of you are able to return should the conversation goes in an undesired direction.

By telling them what their argument has taught you, as stated in the third rule, you present to your partner an instance of the phenomenon known among psychologists as pro-social modeling. To explain it simply, you make them see the conduct you approve. When you submit to your partner’s knowledge, you make a good example of reciprocal respect and openness. You inspire them to take part in a cooperative effort instead of a fight. Even though they don’t take the same steps as you do, this rule proves that their argument provided valuable insight for you. Even with this, it is possible to cool down the heated atmosphere.

Sticking to Rapoport’s Rules might not be easy – particularly during the moment when the conversation gets heated – however, it’ll enhance your conversations.

Chapter 6 – Not all people make up their opinions on the basis of proof.

In 2014, Bill Nye, an American known for his science show on TV, decided to participate in a discussion with Ken Ham, a Christian fundamentalist most renowned for constructing a form of Noah’s Ark based on its qualities in the bible. Their argument centers around creationism. In this notion, God is the creator of the cosmos. Ham defended this argument; Nye thought this argument was wrong – the fundamentals of his views hinges on Darwin’s theory of evolution.

The moderator posed each of them this question: what could make them alter their views.

Nye responded to this question by saying “Evidence.” As for Ham, his response was “Nothing.” There was no way his views could transform.

For people for whom the most important thing is evidence, it is usually difficult to comprehend a person like Ham. As a result, it renders conversations difficult to have.

People who share the same view as Bill Nye care about observations and verifiable truths. They usually believe that the other group lacks a fundamental piece of evidence. Only if the other group proves their point, will they certainly alter their views abruptly, won’t they?

However, for people like Ham need no evidence, as the group that Ham represents are fully cognizant of whatever there is know about, which is in total contrast with the opinions of the group Nye represents. There is no single drop of doubt in them that what is written in the Bible is wrong. Nothing’s going to deter them from this immutable belief.

There are more people who believe in creationism than you would imagine. In spite of a great many powerful scientific proofs, a little more than a three-tenth of Americans deny evolution wholly. The reason for this doesn’t stem from them having never heard of scientific truths about evolution; they’ve heard about the facts. The reason is quite straightforward: they just use separate criteria, which have no links to evidence.

For some people, for instance, creationism is a moral issue. What they think is that being a creationist renders them better Christians. Other people believe so because of the people around them. When people in your entourage believe in creationism, believing the Bible truly makes far simpler to be part of the community. This isn’t precisely unreasonable. However, such instances reflect the way people’s moral and social mind is able to outweigh their reasonable, evidence-driven thinking.

If our views are under the sway of moral or social concerns, facts seldom can penetrate into our minds, which follows from the fact that it is very significant for us humans to be “good.” This indicates that people usually hold what the people around express about them in far higher esteem than truths.

Is the meaning we should infer from all of this is that such people as Ken Ham and Bill Nye are never going to have a productive conversation? No, surely they can. As we are going to read in the subsequent chapter, they just have to discover an unconventional way of conversation – where the focus won’t solely depend on facts.

Chapter 7 – When fact-filled remarks fail to make any changes, why not ask logical questions in place of fact-filled remarks.

Think about an atheist who believes her pious coworker’s faith in God is honest but erroneous. What she aims is to alter his idea. According to her thought, she must demonstrate to him novel proof in order to achieve her goal. Thus, she prepares her pieces of evidence smartly, and she discusses attentively. However, something strange takes place. As she continues to discuss her point more, her coworker’s belief strengthens further and believes he’s right.

Most people have crossed the same path. There are times when proof alone isn’t that helpful.

Funnily, when you present truths so as to alter another person’s beliefs, it usually rebounds. Their opinions got further ingrained and firmer. This transpires as a result of this form of discussion wherein your opponent gains a reason to underpin his stance. These people might believe that acknowledging their beliefs are incorrect will cause them to appear “stupid.” Or it might be due to much time, energy, and money put into their belief.

Then, should fact-filled arguments not function, which technique should you adopt in their place?

The important thing is to concentrate on how your opponent rationalizes its belief. At this stage, don’t think about if their opinions are reasonable or not. Rather, pose many open questions. As discussed in previous chapters, questions are perfect when it comes to revealing issues and inconsistencies.

Suppose that according to your friend Paul’s belief, the weight of a soul is equal to precisely seven pounds. You may think this is silly or senseless. Certainly, it is quite simple to refute this idea with empirical evidence. However, take a more earnest approach to Paul’s belief.

You can start by posing the question regarding the reason behind his belief in this. He responds to your question by referring to a German scientist’s renowned experiment. The scientist measured the weights of numerous bodies prior to their death and the aftermath of their death. The result was that a lifeless body’s weight is seven pounds lighter than an alive body.

At the moment, suppose this belief makes sense. However, pose some follow-up questions as well. According to his belief, then do four-pound babies also weigh seven-pound as souls? When he affirms it, ask this: does it indicate a baby’s weight would be down to minus three pounds the aftermath of death?

Ultimately, it is possible to pose questions called disconfirming questions. Such questions inquire how a view is rationalized by posing the question of what would convince them to renounce their opinions. If we continue with our case, it is possible to ask Paul what proof would have him alter his mind views regarding the weight of souls. Would he make a different inference were we to tell him that it would be impossible to rerun the same experiment?

We have examined how influential logical questions can be. In the subsequent chapter, what insights we can gain from hostage negotiators and use them.

Chapter 8 – There is a wide array of things that we can learn from hostage negotiation to enhance conversations

By now, we’ve taken help from philosophers and psychologists – two occupations that specialize in tough conversations and crafty questions. However, the final word pertains to a group, the convincing skills of whom concerns most usually the decision between life and death. This group is hostage negotiators. As we’re going to learn from this chapter, there are a lot of techniques we can make use of.

Your opponent may not want as much as a bank robber would, however, this doesn’t prevent us from utilizing a few of the tactics police negotiators apply to. You can make conversations flow more smoothly with these tactics.

Think about the tactic called minimal encouragers. These are subtle indications that carefully make the opponent know you’re paying heed to his words – such signals as “Yeah,” “I see,” and “OK.” Though they don’t require any energy and they’re a no-brainer, minimal encouragers can be very helpful at removing the doubts and fears of your opponent and mitigating tense moments.

One other tactic is mirroring. This is also a straightforward verbal method that informs the speaker you’re paying attention to. Maybe more significantly, it makes them feel that you “grasp” their argument. See the way it functions: if your opponent talks about something, just reiterate the final two or three words – however, rephrase them as a question.

Suppose that they utter this sentence: “I’m really so sick and exhausted of people pushing everyone around!” Your response would be, “pushing everyone around?” The main thing here is to make the speaker go on talking so that they will share more and more information. Anything they utter can be valuable when you both have a conversation.

You should also keep in mind that when you want others to alter their views, you need to provide them a polite exit. As hostage negotiators name it, it is called building a golden bridge. This method is based on the insight that people have more tendency to hold their guns firmer when there is no other option for them to avoid humiliation. So, in reality, the technique can be as easy as highlighting the issue you’re coping with would be fairly challenging for every person, including you.

Lastly, one very good way to generate the circumstances for a good conversation is to start by tackling trivial problems. Begin negotiations by tackling issues straightforward to eliminate. If you manage to find a common ground on the trivial problems from the onset, you’ll build an environment of success. This kind of environment renders it more straightforward to continue to be civil if the conversation shifts to a huge disagreement.

Here’s everything you need – tactics to enhance your communication and leave improbable conversations behind for good.

How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide by Peter Boghossian, James A. Lindsay

This era is shaped by increasing extremism. Having a conversation usually makes you feel this is fruitless. However, it is possible to communicate with people who have morally and politically different views. The reason is that the actual problem doesn’t stem from ideological disagreements – this happens because we’ve forgotten how to have a conversation. If we truly pay attention to people, not giving lectures to them, and understand to talk about the points with which we don’t agree in a civil manner, it is possible to alter one other’s opinions and reconsider our views.

Figure out where the root of the issue is by paying attention to your “moral dialect.”

We usually think that we speak in a normal manner and other people have “accents.” This sort of indicates that each of us has a different accent. The exact thing goes for how we discuss the things we hold in high regard. Each of us has “moral dialects” which seem natural to us despite being remote, or even not understandable, for strangers.

This makes paying heed to your own moral dialect a great idea. Consider the way you employ words like “racism” or “freedom.” Is there a separate meaning when people think of these words? When you start considering it in this way, you’ll be able to see the root of conflicts. Do your views really clash with those of others, or is it because of the words they use? To explain it in a different way, is it semantics or worldviews that you’re clashing for?