Nowadays, Friedrich Nietzsche is a key name throughout the entire existence of reasoning – a late nineteenth-century figure whose unpredictable works demonstrated gigantically powerful to numerous future developments, including existentialism. In any case, his expert profession was not a triumph; he just picked up prestige after his plunge into franticness.

Nietzsche’s vocation started stunningly. He was named Chair of Classical Philology at only 24 and before long made the colleague of the incomparable Richard Wagner. In any case, the books he distributed failed, his well-being decayed, and he inevitably capitulated to psychological maladjustment.

For what reason was Nietzsche’s life so troublesome? What were his books truly about? Furthermore, what kind of impact did he wind up having on the world? You’ll discover in this rundown!

Chapter 1 – Friedrich Nietzsche’s initial years set him on an extraordinary scholarly way.

A wiped out yet splendid understudy at Leipzig University – Friedrich Nietzsche – got an extraordinary greeting one day in November 1868. Yet, he nearly didn’t make it; a very late conflict with his tailor’s associate left him without formal nightwear.

Running late, Nietzsche needed to run through the heavy storm without a supper coat to meet the one who might turn into his guide and companion: the incredible writer and polemicist Richard Wagner.

The two reinforced over Wagner’s music and their shared gratefulness for crafted by the then-dark thinker Arthur Schopenhauer. Nietzsche left with a loving greeting to visit Wagner at home.

It was a little glimpse of heaven for youthful Nietzsche, whose extraordinary acumen and energy for music were apparent from youth.

Nietzsche was conceived in the Saxon town of Röcken in 1844 to his mom, Franziska, and Lutheran clergyman father, Karl Ludwig. His sister Elisabeth was brought into the world two years after the fact; Friedrich tenderly called her “Llama.”

Misfortune struck the family in 1849, when Karl Ludwig kicked the bucket following quite a while of loathsome ailment and close visual deficiency, at only 35. His primary care physicians credited the reason for death to a mental condition. Youthful Friedrich was likewise inclined to serious migraines and eye torment, which now and again surrendered him confined to bed for to seven days.

The family at that point moved to the bigger city of Naumburg, yet from the age of 14, Friedrich boarded at the Schulpforta – the nearby tip-top school. Despite his fragile well-being, Nietzsche dominated, demonstrating a specific inclination for philology, the investigation of old dialects and writings.

He at first proceeded with his examinations at the philosophical workforce in Bonn to satisfy his mom’s desire that he enter the pastorate. Yet, his mind was attracted to philology, and he before long left Bonn to contemplate it in Leipzig with teacher Albrecht Ritschl.

Not long after his gathering with Wagner, the intelligent understudy was offered the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in Switzerland. At only 24, he was the most youthful individual actually to be selected for this post.

Chapter 2 – Enchanted by the Wagners, Nietzsche composed his first book in unspoiled Lucerne.

Nietzsche was excited by this arrangement – especially as Basel was close to Lucerne, where Wagner lived. When settled, he brought the train down to the lake, advanced toward the Wagner habitation, and thumped on the entryway.

Wagner’s home in Lucerne, called Tribschen, was heaven for Nietzsche. The resplendent estate turned into a subsequent home – complete with his room – as his fellowship with both Richard and his significant other, Cosima Wagner, prospered.

The author was somewhere in the range of 30 years Nietzsche’s senior, yet they fortified over discuss reasoning and music. Nietzsche’s traditional instruction dazzled Wagner, who was partial to Greek misfortune yet couldn’t peruse the language. The youthful Nietzsche was enchanted by the virtuoso of his new companion and spellbound by the powerful character of Cosima.

The three became indistinguishable companions – so close that Nietzsche was once entrusted with purchasing new silk undies for the author. There were likewise tremendous strolls in the encompassing mountains including Mount Pilatus, the mythical site of Pontius Pilate’s self-destruction after the execution of Christ.

In any case, Wagner was not by any means the only compelling mastermind Nietzsche become a close acquaintance with during this time. The unconventional educator Jacob Burckhardt turned into a scholarly fighting accomplice. Burckhardt was a progressive, yet he disdained patriotism. In contrast to the combative Wagner, Burckhardt feared the approaching apparition of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

Nietzsche filled in as an emergency vehicle orderly during the war and was dismayed by the obliteration he saw. Yet, it was just a short time before his sensitive well-being required he leave this post. He got back to Basel solidly restricted to the contention.

Even though Nietzsche and the Wagners disagreed on this issue, the kinship suffered for now. Nietzsche’s first book, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, remains as a confirmation: Nietzsche wrote it as a sort of favorable to the Wagner proclamation. In it, he asserts the old Greek dramatists as an honorable point of reference to Wagner’s new type of “music dramatization,” typified by Tristan and Isolde and The Ring Cycle.

The book presents the contention between the arranged, rich Apollonian and the wild, happy Dionysian – a duality vital to quite a bit of Nietzsche’s idea. Music and misfortune were both Dionysian fine arts, equipped for moving the soul to a condition of rapture.

The Wagners cherished Nietzsche’s book, yet their time in Lucerne had concluded. Loaded up with affectionate recollections, they moved to Bayreuth in 1872 to regulate the creation of the show house where the Ring would be performed. Then, Nietzsche indeed fell into sickness.

Chapter 3 – Nietzsche battled with his vocation, his well-being, and his connections after The Birth of Tragedy.

After The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche’s heavenly scholarly vocation quickly plunged. Oddly conflicted about the occasions, the book gathered no consideration from Nietzsche’s companions and individual researchers. His previous instructor, Professor Ritschl, composed an obliging letter to the creator however wrote cursing decisions in his duplicate. Burckhardt was moreover courteous yet neutral.

Nietzsche likewise looked for scrutinizing on a melodic work he had formed, however, even the Wagners stayed quiet. The conductor Hans von Bülow inevitably gave him input – yet it was savage. “Is this all some terrible joke?” he inquired.

So, the rising star out of nowhere ended up solidly back on earth.

The work was a hit to Nietzsche’s scholarly notoriety, and just two understudies pursued his philology course in Basel after distribution. Not that Nietzsche truly was a philologist any longer – he was unquestionably more intrigued by theory. He kept composition and left on a progression of what he called Untimely Meditations, yet this book, as well, met with a crisp gathering.

The pressure demonstrated a lot for his wellbeing, which calamitously declined. He got incapable to endure common light. For any excursion outside, he wore thick, colored glasses and a sun visor. His sister Elisabeth, still unmarried, turned into his parental figure and in the long run moved in with him to offer consistent help.

Then, his relationship with the Wagners was fraying. His first outing to visit them in Bayreuth felt off-kilter. Wagner later offered Nietzsche some paternalistic exhortation, recommending he wed – counsel ineffectively got by the slight youthful scholar.

When a wunderkind, Nietzsche presently wound up approaching 30 with a terrible – and further declining – scholastic notoriety. He was ever-aware of his dad’s initial demise, anticipating the equivalent for himself.

From this depressing spot, a few positives rose. One of his Meditations, “Schopenhauer as Educator,” was moderately generally welcomed, and he found an anxious pupil in the youthful writer Johann Heinrich Köselitz, who turned into his secretary. The controlling Nietzsche would later make the peculiar stride of renaming him: he called him “Subside Gast.”

He likewise becomes friends with the maturing rebel Malwida von Meysenbug, who turned into an adoptive parent-like figure, and the philosopher Paul Rée, who acquainted Nietzsche with the realism of Voltaire and significantly impacted his reasoning.

Rée additionally acquainted Nietzsche with a young lady, with far more noteworthy outcomes.

Chapter 4 – After Human, All Too Human, Nietzsche went through years meandering around Europe.

Notwithstanding late mortifications, Nietzsche outlined a strong, new learned course in 1876. Human, All Too Human was his first book written in an aphoristic style, succinct and epigrammatic. He committed it to Voltaire – regardless of the dissatisfaction with regards to Wagner.

Nietzsche was cutting his way, and it turned out to be evident that his future didn’t lie in philology. In 1879, he left Basel, accusing chronic frailty. While not false, it was a long way from the full picture.

The college conceded him benefits for the following six years, managing him some monetary dependability. Be that as it may, next to no else stayed stable in the way of life he decided to receive.

Human, All Too Human contends that there is no unceasing truth – everything is dependent upon conditions. Critically, that incorporates religion, which Nietzsche unhesitatingly attacks. He similarly alerts against daze confidence in science; we should address science as heartlessly as religion.

This scholarly development satisfied Burckhardt and Rée yet irritated numerous others – including Nietzsche’s Christian sister. Richard Wagner declined to understand it, however, Cosima did. She credited its failings to the malignant impact of Paul Rée – a Jew.

Nietzsche called this period his Wanderjahre – his long stretches of meandering – in which he investigated Alpine Europe from a progression of resorts. He meandered without a perpetual home, our identity, having surrendered his citizenship when he moved to Switzerland.

He composed Daybreak, depicting himself as a “pilot of the soul,” taking off above others in the Alps. He became especially partial to the cool summers in Sils-Maria, a town close to St. Moritz. However his well-being – especially his eyes – stayed poor.

Rée wrote in 1882, entreating him to come to Rome and meet the youthful Lou Salomé, an exceptionally smart and beguiling young lady and future pioneer in analysis; Nietzsche acknowledged. In any case, this was no conventional matchmaking. Lou’s craving was to live with both Rée and Nietzsche, in an enthusiastic however non-romantic ménage à trois.

Charmed, the two men concurred. In any case, this purported “heavenly trinity” was a long way from agreeable, as the two men continually competed for Lou’s consideration.

On one event in May, Nietzsche and Lou got away from Rée to climb the fearsome Monte Sacro. High over the Italian lakes, they talked about the way of thinking with an uncommon force, and he unveiled to her his most profound contemplations. He positioned this among the best encounters of his life.

Chapter 5 – Nietzsche’s always sure way of thinking was conflicted about his turbulent private life.

The very year that Nietzsche trapped himself among Rée and Salomé, 1882, he wrote the scandalous words: “God is dead.”

The first show up in quite a while book The Gay Science. Nietzsche recounts the account of a crazy person going through a commercial center, hollering: “God is dead! God stays dead! Also, we have slaughtered him.”

However, the focal inquiry of the book is, What would it be a good idea for us to do now? Nietzsche was charmed by the ethical vacuum that may arise as the old strength of Christian creed appeared to be ready near the precarious edge of elimination. What lay ahead for humanity, without a controlling good power? The future could spell misfortune, he watched.

Nietzsche’s future, then, was dubiously bound to his inquisitive relationship with Lou Salomé and Paul Rée.

Notwithstanding Nietzsche’s break with Wagner, the 1882 debut of Parsifal in Bayreuth was such a significant social function that it constrained acknowledgment. It was Wagner’s first new work since The Ring Cycle.

In any case, Parsifal’s profound Christian impact affirmed the striking cacophony that had created among Nietzsche and Wagner’s ways of thinking. All the more actually, Nietzsche was not welcomed by the author thus wouldn’t join in. Yet, he utilized the open door for what he thought about a shrewd ploy.

He chose to send Lou to the debut alongside his sister, Elisabeth, to reinforce his familial bond with Lou – and avoid the desirous Rée.

The excursion was grievous. You delighted in the blue-blooded climate, and her coquettish disposition stunned Elisabeth. Then, Elisabeth needed to fight with pernicious tattle about her sibling. This incorporated the news that five years sooner, Wagner had written to Nietzsche’s PCP about his doubts that the thinker was stroking off – accepted at an opportunity to cause visual deficiency. Alongside a shocking image of Lou shaking a whip at Nietzsche and Rée, this turned into the discussion of the celebration.

Elisabeth left early, however, the two had organized to join Nietzsche after the celebration at a close-by resort. This, as well, ended up being an especially off-kilter occasion.

With the moping Elisabeth staying home, Nietzsche and Lou went for long backwoods strolls, during which the philosopher examined his thoughts with heartfelt power. It demonstrated a lot for Lou. She and Rée fled together not long a short time later.

Nietzsche was crushed. Yet, having proclaimed the demise of God, he was flooding with thoughts for his composition.

Chapter 6 – Nietzsche composed the elated Thus Spoke Zarathustra during a period of extraordinary torture.

Staggering from Lou’s flight, Nietzsche’s well-being endured gravely throughout the colder time of the year of 1882-83. His decision of prescription didn’t help – he started taking opium, which he affirmed in a progression of disturbing letters sent from his transitory home in Rapallo, a beachfront town close to Genoa.

On Christmas Day, notwithstanding, he started composing what might get one of his generally noteworthy and compelling works: the philosophical novel, Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Yet, for all, it’s melodic to discuss a “superman,” Nietzsche himself was more debilitated and delicate than any other time in recent memory.

Nietzsche distributed Thus Spoke Zarathustra in four books, however, the first was the most persuasive. In it, Zarathustra, an old Persian prophet, slips from a mountain following ten years of isolation. He lectures: “Person is something that must be survived.” The superman must rise in its place.

Nietzsche avoids characterizing precisely what he implies by “superman,” however he portrays a solid chief who can resolve the ethical emergency tormenting humankind since the passing of God. For the superman, the demise of God is freeing – not a reason for skepticism.

Nietzsche was in Genoa to present the composition on his distributor when he discovered that Wagner had kicked the bucket the day preceding. He thought about this as a sign.

The second book of Zarathustra uncovers Nietzsche’s profound injury at the selling out of Lou and Rée – the “tarantulas” portrayed in his, not at all subtle content. Nietzsche acknowledged how personal it was with shock. The third book closes with a satire of The Revelation, the last book of the Bible, where he proclaims he cherishes no lady aside from “Forever.” In the fourth book, Zarathustra invites an assortment of persuasive considers along with his cavern – including the Pope, Schopenhauer, Wagner, and Nietzsche himself.

Nietzsche’s mom viewed his books profane, however, there was an additionally squeezing issue causing family bedlam. To the alert of both Nietzsche and his mom, sister Elisabeth had gotten drawn into the German patriot Bernhard Förster, a vocal ally for the establishment of another German settlement in Paraguay – one liberated from “Jewish impact.” Nietzsche didn’t uphold this development.

In the interim, his well-being proceeded with its precarious decay. One associate stayed with him in 1884, to discover him insane and in a troubled state; she presumed he was utilizing opium or hashish. He inquired as to whether she suspected he was going distraught like his dad. She was alarmed.

Chapter 7 – Regardless of his accounts, wellbeing, and notoriety, Nietzsche continued composing his combustible books.

While the third some portion of Zarathustra was Nietzsche’s eleventh distributed book, none of his works had sold well – not so much as a hundred duplicates by and large. His distributer Schmeitzner pulled back help. Even though he was happy to disavow Schmeitzner, an enemy of Semite, this was as yet a blow for Nietzsche.

Another worry was his benefits from Basel. Due to terminate in 1885, the college generously chose to reestablish it for an extra year. All things considered, Nietzsche was running out of cash.

All things considered, he kept on emptying his restricted assets into his books – presently paying to independently publish.

The shaky, close visually impaired thinker proceeded with his European visit, spending the mid-year months in the Alps and the winters on the coast. He was an accommodating and affable visitor in the modest inns he frequented. He kept up exceptional weight control plans in the vain expectation he may fix his unlimited episodes of devastating sickness.

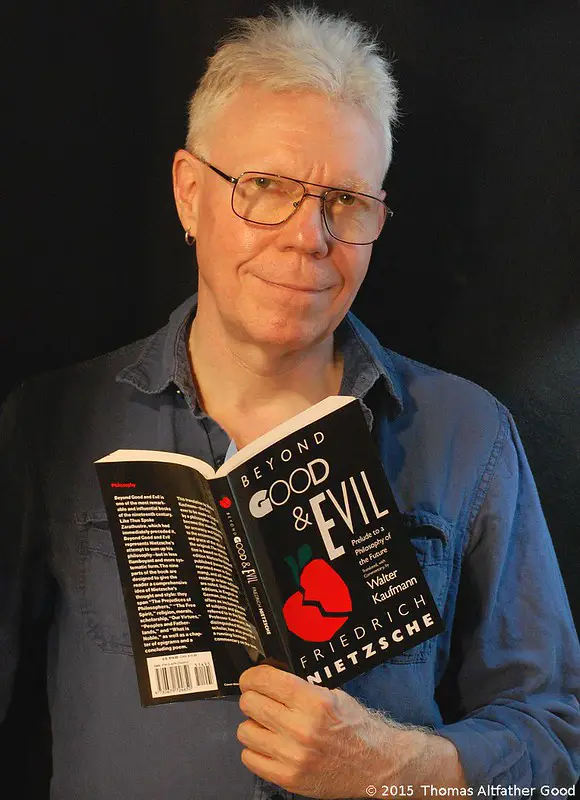

However, he figured out how to create two gratings, new works: Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morality.

As the primary book’s provocative title proposes, Nietzsche urged perusers to quit considering great and detestable as absolutes. Or maybe, they are simple shows, a result of both the ancient Christian confidence and a philosophical convention extending back to Plato.

Rather, we should receive the ethical quality of the superman, a free soul is driven by what Nietzsche called the “will to control” – that would someone say someone, will live intensely, scrutinizing each conviction with an open-finished, “Imagine a scenario where.

On the Genealogy of Morality expands this contention and quickly refers to another idea: the “fair monster.” This expression is regularly viewed as a connection among Nietzsche and the Aryan governmental issues of Hitler. Be that as it may, Nietzsche asserts this lurking, eager for power is, truth be told, basic to all races – not simply the Germans.

The intensity of Nietzsche’s writings was at last accumulating interest, and not at all like the greater part of his books, Beyond Good and Evil pulled in a survey. The pundit, be that as it may, portrayed it as “risky.”

Then, his sister and her new spouse were gaining ground of their own, in a more famous design. They set up Nueva Germania in Paraguay – planned as a magnificent new home for the Fatherland. They had just persuaded 14 families to accompany them, and the misinformed venture immediately self-destructed. Be that as it may, Elisabeth delighted in her sovereign like status and kept up a strong stream of purposeful publicity in the German press.

Chapter 8 – Nietzsche at long last began to get basic consideration – however, something wasn’t right.

Nietzsche’s profession got an uncommon lift In 1887. He sent duplicates of his books to Georg Brandes in Denmark, one of the most famous abstract pundits of the day. Brandes was intrigued by what he read and kept in touch with Nietzsche in recognition of his “refined radicalism” – an expression Nietzsche venerated.

Notwithstanding getting an abrading letter from his sister Elisabeth in Paraguay – Brandes was Jewish – Nietzsche realized he was on the way to genuine acknowledgment. Accordingly supported, he kept composition.

Be that as it may, everything was a long way from well. His old companion Erwin Rohde was among the first to presume there was something malevolently amiss with Nietzsche, past his standard wellbeing grumblings.

His conduct would out of nowhere become unusual or even uncanny, Rohde watched, and his manner of speaking was upsetting. Nietzsche declaimed his incredible predetermination as to the messenger of another philosophical age. He seemed hallucinating, and Rohde disavowed.

In 1888 Nietzsche found Turin. It was a city that fit him well as a “blue-blooded revolutionary,” and he added it to his yearly timetable, close by Nice and Sils-Maria.

In Turin, he by and by taking up his fixation on Richard Wagner, presently a disdain figure. He composed the accursing The Case of Wagner followed by Twilight of the Idols – a reference to Twilight of the Gods, the fourth aspect of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Captioned “How to philosophize with a mallet,” this book recharged the writer’s assault on both ways of thinking and religion.

His next work, The Anti-Christ, made natural progress, even though its last area struck another and upsetting note. It upheld the battle against Christianity and required the capture of clerics. He marked the book “The Anti-Christ.” It’s hard to decide whether Nietzsche was being not kidding or humorous – or, maybe, simply showing psychosis.

Always persuaded of his significance – apparently affirmed in the recognition of Brandes – he started to deal with his personal history. He entitled it Ecce Homo, the words verbally expressed by Pontius Pilate when he introduced Christ for torturous killing. Nietzsche contrasted himself with Christ now and again in its pages, whose initial two sections were named “Why I Am So Wise” and “Why I Am So Clever.”

“I know my destiny,” he composed. He anticipated that “something terrible” would one day be related to him, for “I am not a man, I am explosive.”

Chapter 9 – The fanciful Nietzsche slipped into franticness.

By Christmas of 1888, Nietzsche had composed one more concise book, Nietzsche contra Wagner, and read through his distributed work to date. It was all great, he understood. What an amazing, visionary essayist he was – Ecce Homo specifically. “There is no corresponding to it even in nature herself,” he composed.

In this blissful state, he wrote a progression of peculiar Christmas letters, incomprehensibly misrepresenting his status. He marked a bewildering letter to the writer August Strindberg as “Nietzsche Caesar” and others as “The Crucified.” A letter to Cosima Wagner read basically, “Ariadne, I love you. Dionysus.”

A letter to Burckhardt enormously stressed the benevolent educator. He took it to Nietzsche’s companion Overbeck, and the two of them concurred something must be finished.

Nietzsche’s dreams had developed bit by bit, yet there was a crucial point in time for his psychological well-being in January 1889. He separated sobbing in a Turin road at seeing a pony being beaten. His proprietor showed up at the scene and accompanied him back home. Nietzsche went through a few days in his room, singing uncontrollably and slamming around bare before Overbeck showed up.

Going along with his daydreams, Overbeck convinced Nietzsche to accompany him to a center in Basel. His conduct there was unpredictable – in some cases forceful, once in a while quiet. He seemed to accept he could control the climate. Syphilis was regularly given as the reason for his psychological decay, however, tests at the time were uncertain.

In March 1890, he left the refuge in the authority of his mom. They before long moved back to the family home in Naumburg. He stayed there for quite a long while, encountering fanciful wraths and being completely subject to his mom.

In 1893, his sister Elisabeth returned. Her significant other had ended it all in 1889 amid the disappointment of their Paraguay adventure, and after three years the test finished. She detected more prominent open doors back in Germany, where her sibling’s craziness and the public’s enthusiasm for his philosophical work were expanding inseparably.

She worked rapidly to set up what she called the “Nietzsche file” and started to develop her sibling’s developing legend. At the point when their mom kicked the bucket in 1897, Elisabeth sold the family home in Naumburg and moved to Weimar – the renowned social city of Goethe and Schiller.

She bought a huge domain with the assistance of Meta von Salis-Marschlins, a concerned companion of Nietzsche’s, with space for her now insane sibling to be kept far out higher up.

Chapter 10 – Nietzsche’s work turned out to be gigantically powerful, however, he never knew.

Nietzsche never knew genuine progress as a philosopher, however, his notoriety took off some time before his demise. Broad acknowledgment thrived during his time of franticness.

An all-around associated youthful check, Harry Kessler, found Nietzsche’s work in 1891. Propelled, he worked eagerly to advance Nietzsche in his persuasive circle. Nietzsche, to Kessler and others, was a free soul and a loss of independence. The possibility of the superman instead of God was especially thunderous. Hence Spoke Zarathustra, specifically, turned into a popular book.

Unbeknownst to the deranged Nietzsche detached in his youth home, his work propelled the Strindberg to play Miss Julie, Munch’s acclaimed painting The Scream, and an entire age of perilous, revolutionary masterminds, including Mussolini.

Elisabeth had gone through years developing the legend of Nueva Germania to a faraway German crowd, and she left on a comparative undertaking of fantasy working for her sibling’s heritage. She kept up severe command over his correspondence and index of books. Duty regarding the domain had initially tumbled to her mom, however, Elisabeth got her out.

Afterward, the manor in Weimar turned into such an exhibition hall for especially dedicated Nietzscheans, and Elisabeth facilitated salons and gatherings. Realizing that the thinker himself was meandering around higher up gave these functions an evil rush. Visitors were here and there even permitted a brief look at him.

Nietzsche kicked the bucket in 1900. Disregarding his last wishes, Elisabeth orchestrated a Christian memorial service.

Elisabeth lived on until 1935, savagely controlling the file of her sibling’s work. She achieved extensive achievement: her compositions on her sibling won her a privileged doctorate and four Nobel Prize designations.

Ever the submitted German patriot, she took incredible consideration to advance her favored translation of Nietzsche’s work. Even though Nietzsche himself had not been a patriot his ideas of the “will to control” and the “light monster” were co-picked by patriots as the First World War drew closer.

Afterward, the Nazis went further still in utilizing Nietzsche’s writings – from Elisabeth’s specifically altered releases – for their finishes. Hitler visited Elisabeth at the file in the wake of turning out to be Chancellor in 1933 and again in 1934 when he appointed a Nietzsche commemoration from his favored draftsman, Albert Speer. He went to Elisabeth’s memorial service the next year.

In 1884, Nietzsche had kept in touch with his sister trusting his dread of what perilous individuals may one day do in his name. In any case, he composed, that was inescapable for an incredible instructor – one may wind up a gift for humanity, or a fiasco.

I Am Dynamite!: A Life of Nietzsche by Sue Prideaux Book Review

Notwithstanding his prestige today, Friedrich Nietzsche was a dark figure for an incredible majority. He experienced horrible well-being and was conflicted about the scholarly atmosphere of his day. When approval, in the long run, showed up, he had dropped into a frenzy, and his heritage was controlled by his sister Elisabeth.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks