Does the politics of America look more controversial than ever before? Definitely, it does. However, Trump isn’t just the only president whereby his impeachment crisis has crushed American democracy to a stop. In this book chapter, you’ll get to know what the writers of the US Constitution –usually referred to as “the Framers” – were considering when they created the executive branch of government and their deliberately difficult system for eliminating a corrupt executive. Nowadays, this is what we refer to as impeachment.

Before Trump’s impeachment, just three US presidents ever encountered impeachment, namely: Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton. Just two of them were really impeached: Johnson and Clinton. Nixon retired before the House could finish off. The information of these three crises vary from shameful to motivating, and each brought about lasting transformation in the American system of government.

Chapter 1 – In spite of their terror of monarchs, the Framers knew that an executive branch was needed to handle the chaos.

Do you recall how good it was when you eventually left your parents’ house and were released of their authoritarian instructions? Also, how frightening it was when you knew you now needed to be an adult? That was America immediately after it won the Revolutionary War against the British. For a moment, the brand-new nation was not doing good with its independence.

Confusion reigned in the outcome of the war. The alternative political system that appeared wasn’t working for everybody. Ruled mostly by legislatures, a lot of post-revolution states fell toward mob rule. For them to maintain their seats, legislators were required to behave in a manner that would please, instead of benefit, the people.

Even worse, now, Americans were fighting with each other over the exact problems they’d recently fought the British. In 1786, during the winter, there was a fight in Massachusetts between backcountry farmers and private militias supported by Boston aristocracies over who had the right to impose and receive taxes.

Directing power in only one person, as in a monarch or other executive, was still a contentious view in post-revolution America as well. James Madison, the fourth president was concerned that “a lot of people of weight,” desperate for stability, were encouraging for a return to monarchy, a clearly damaged; however, conversant system. Other communities tried out eliminating executive power completely, like the states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Somebody needed to make some rules – and quickly. July of 1787, The Founding Fathers assembled in Philadelphia to figure out a system of government, in a meeting called the Constitutional Congress.

Obliged to thin through their radically pro-legislature positions, and scared of the softening public position toward monarchy, the Founding Fathers got to know that they would have to form an executive position nevertheless. They had to make the government more effective, to put the legislature into shape, and to signify the united will of the people, instead of only one group of constituents. This position would turn into the president.

However, there was fear at the idea as well. Going back to Europe’s long history of tyrannical, self-serving kings and rulers, they concerned about whether giving a lot of power in a single person’s hands would have a corrupting effect on the president. In order to evade what looked to them like an inevitability, the Framers devised a means for the legislature to defend against corrupt executives in the future. This turned out to be the process we understand as impeachment.

Chapter 2 – The Framers deliberately formed impeachment as vague, difficult protection against corrupt upcoming presidents.

The Framers realized that a president would be required; however, they weren’t ready to allow him to pull any king-like pranks. But, how would they know, what kinds of trouble presidents would face centuries after? They needed to write the Constitution in a manner that was really specific to allow future Congresses to get rid of a corrupt president; however, really flexible to adjust to changing periods.

The first people who proposed “high crimes and misdemeanors” as a term to validate taking out a president was Virginia planter and constitutional delegate George Mason. It’s turn out to be one of the most popular words in the entire Constitution.

The matter in front of the Constitutional Congress was the way to ensure that upcoming legislators wouldn’t have the power to impeach a president for garden-variety uselessness or stupidity. A president needed to have evil intentions. The word “high crimes and misdemeanors,” roughly defined as a crime against the entire American people, was perfect: serious-sounding; however, in the long run vague.

Up till now, Constitutional scholars still debate about what the meaning is. However, just when you believe the definition is getting clear, it becomes vague once again. It turns out a president doesn’t really need to perpetrate a crime to be impeachable. The only thing he or she needs to do is make the way for the crime to be perpetrated, or do nothing to put a stop to the crime.

The impeachment process of the Framers isn’t only unclear; it’s very difficult too. This, as well, was deliberate. The Framers were aware that impeaching a president entailed undermining the will of the people who had chosen him or her as the president. Bearing that in mind, they assumed the process has to be done with the greatest gravity and reflection.

For one thing, to successfully get rid of a president, articles of impeachment would need to pass through both chambers of Congress: drawn up by the House of Representatives, approved, and then confirmed by the Senate in a trial controlled by the Supreme Court Chief Justice.

However, that’s essentially everything the Framers give us. There is nowhere in the Constitution that mentions the rules for a Senate trial, or the control the House possesses to subpoena information or impeach a current president. It would be left to the upcoming congressional leaders to resolve these details, in the actual-time disorder of a political crisis.

And what happened after was most likely beyond the Framers’ wildest dreams.

Chapter 3 – The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson’s in 1868 confirmed that Congress can’t impeach a president only because he’s unbearable.

How frustrating is it when a person is really horrible; however, you can’t get a reason to remove them? In the year 1868, the members of the US House of Representatives were confronted with this actual problem. However, they chose to impeach President Andrew Johnson nevertheless –only because he was hated and annoying, not because he violated the law.

The obstinate Democratic president, who came into power after President Abraham Lincoln was killed, was very disliked with the Republican-controlled Congress. It was just a matter of time before things get physical.

Congress’s hatred of Johnson looks defensible: by all means, he was a jerk. Not just was he angry, hot-blooded, and completed– he was extremely racist, even for the disgraceful standards of the time. Having been brought up in a poor white family in North Carolina, white supremacy offered him a sense of identity. That made him annoyed and hostile about the Confederacy’s defeat of the Civil War. Later, he really mentioned that “just white men should control the South.”

Johnson frequently undermined congressional attempts to encourage racial equality in the South. Firstly, he rejected the 14th Amendment, which released the slaves. Afterward, he prohibited two bills that assured civil rights and suffrage to previous slaves. Eventually, he prohibited the Freedmen’s Bureau bill, formed to assist previous slaves to get back up.

The House was angry: it attempted to impeach him on three occasions on weak grounds before eventually getting a justification. The articles of impeachment were just on the basis of hatred for the man, not on an actual crime.

The House’s main charge against Johnson was that he had broken the Tenure of Office Act, which prohibited presidents from dismissing office-holders without the consent of the Senate. This exact Congress, understanding that Johnson harbored a complete hatred for the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, had approved the act in the year1867 as a trap for Johnson. Johnson walked straight into the trap: in 1867 he relocated to fire Stanton, which brought about his impeachment the next year.

The other articles of impeachment were completely trivial, as well as some congressional claims. Congressmen complained that few of Johnson’s speeches comprised nasty-spirited jokes about Congress. Also, they violently accused Johnson of being connected in Lincoln’s murder. One of the congressmen even recommended that a suitable penalty for Johnson’s act would be exiled to outer space.

Eventually, the Senate couldn’t take the House words seriously. In 1868, Johnson was found not guilty and celebrated with “much whiskey and party,” in the words of a modern.

To impeach a president without having a strong infringement of the law threatens the subtle balance of power intended by the Framers. In the following chapter, you’ll discover what occurred when there was a strong violation.

Chapter 4 – The impeachment crisis of Nixon pushed Congress to update the impeachment process as well as form new rules on executive privilege.

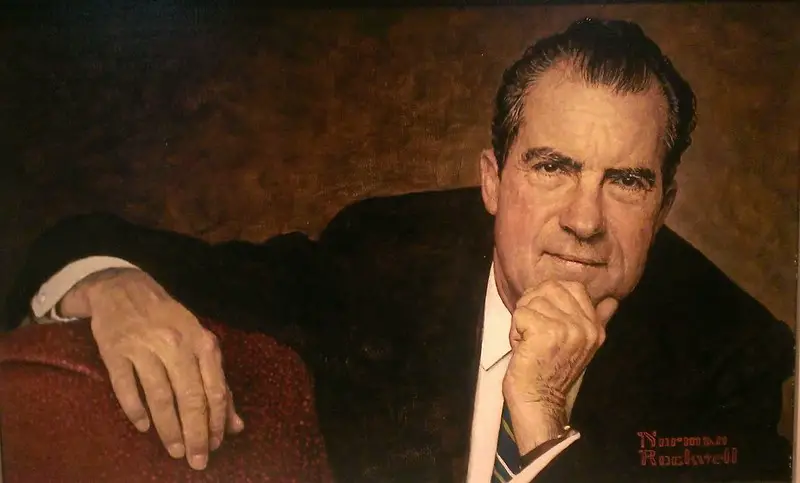

After the crisis of Johnson, the majority of the people in Washington assumed impeachment had been discredited as a tool for a clearly biased Congress. In the year 1974, Richard Nixon, the Republican president as well as his workers were caught acting really bad that Congress started talking about impeachment from obscurity, continuing from where the Framers left off.

Nixon’s deeds were shameless, and his cover-up worked for a very long time. To begin with, in the year 1972, there was the Watergate break-in, whereby thieves linked to the president were caught at the Democratic National Committee headquarters planting listening devices. Three days after, Nixon told the CIA to lie to the FBI, which was charged with the investigation. Afterward, he approved silence payments to the thieves and commanded the IRS to bother his political rivals for tax avoidance.

Eventually, he sacked the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General for not agreeing to sack the special prosecutor responsible for the investigation of the White House. This destruction, referred to as the Saturday Night Massacre, was the start of the end for Nixon.

Eventually, Nixon was simply obliged to release subpoenaed tapes of implicating discussions– that he had taped himself– by a unanimous Supreme Court ruling. The ruling, an outcome of several years and back-and-forth in all three branches of government, create restrictions on how much the president could hold back subpoenaed proof on the basis of executive privilege – the right of the president to private communications.

As soon as his public and congressional backing diminished, Nixon fell fast.

During 1974, in March almost two years after the real Watergate break-in, just a bit over a third of Americans supposed Nixon’s dismissal from office. It was over half by April. By August, he had quitted, deciding to take action before Congress could impeach him.

The impeachment crisis of Nixon’s obliged Congress to set new laws for the impeachment process. They formed the House Judiciary Committee, under the control of Peter Rodino, New Jersey congressman. Among other accomplishments, Rodino as well as the committee additionally defined “high crimes and misdemeanors” to comprise crimes not personally perpetuated by presidents; however, which they made possible or left not reported.

More significantly, the committee members discovered a means to work across party lines: a bipartisan group of unresolved congressmen in the committee became called the Fragile Coalition. The committee was admired even by its contenders as well: Carlos Moorhead, Republican senator mentioned that he believed Rodino was “bending over backward” to be fair. This signified that as soon as evidence eventually became obtainable, no one could assert that the committee had partisan hidden reasons. The reason justice was done well in the case of Nixon was the House Judiciary Committee.

Chapter 5 – The impeachment of Clinton was an additional referendum on executive privilege, and also on changing opinions of morality.

In the 1990s, the standard of morality in the US would have been unrecognizable to its Founding Fathers. Consider the example of President Bill Clinton, whose job approval ratings really increased during the time of his impeachment, in spite of the publication of tawdry information about his sexual adventures that would have allowed George Washington to spit out his dentures.

The crimes of Clinton were eventually more moral than legal. The scandal of his impeachment started when his relationship with Monica Lewinsky, the White House intern became obvious to Kenneth Starr who was the prosecutor in charge of a lawsuit associated with a different Clinton’s marital recklessness. Then, Starr concentrated on Lewinsky, who had appeared to save a specific blue dress which had been stained in a rendezvous with the president.

Caught unexpected by how much Starr was already aware of; initially, Clinton attempted to evade questioning by insisting executive privilege and afterward lied about it under oath. He did a few wonderful linguistic backflips as well: when he was questioned with a yes or no question that depended on the word “is,” he responded, “that rests on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

The main Republican tactic for impeachment was to try to humiliate Clinton by publicly disclosing the entire sordid information of his relationship with Lewinsky. This strategy was unsuccessful because it was out of touch with the loosening American mores of the late 1990s concerning sex and marital unfaithfulness.

The Starr report was released completely, as well as scandalous, unclear pornographic information of the affairs between Clinton and Lewinsky. It was humiliating for everybody and assisted the Democrats to depict the whole issue as offensive and invasive.

Also, in drafting the articles of impeachment, Republican lawmakers borrowed freely from the Nixon impeachment papers, at times in the same words. Americans weren’t just swayed that the wrongdoing of Clinton’s was as worse as Nixon’s.

These impeachment processes eventually led to court rulings that restricted executive privilege more. New laws passed that there shouldn’t be attorney-client privilege between a president as well as his government-paid lawyer, and there is no right to privacy concerning Secret Service agents, both of which Clinton attempted to invoke to protect his secret relationship with Lewinsky.

The sex scandal of Clinton and the following impeachment travails lay the basis for Trump’s impeachment, whose sexual recklessness is a situation of record and who depends strongly on a personally-paid legal team, with whom he most definitely has attorney-client privilege.

Chapter 6 – Impeachment is the outcome of a maliciously partisan political environment; bipartisanship is needed to get through it.

Ask any kid who is in kindergarten how a group can answer a problem and they’ll probably say by “working together.” A person should tell the people living in Washington.

Impeachment has usually been the outcome– and the reason –for a fractious partisan political atmosphere. In order to sell that kind of vague, difficult process to the people of American, opposing parties need to depict their own side as not only right but righteous as well, and their contenders as not only wrong but risky. This entails that every impeachment disaster has frayed the fabric of US democracy, in making it a political problem for contending teams to work with each other.

Worse, Watergate eroded public trust in the US government’s top office permanently. Before Watergate, over 50% of Americans put their trust in the president to do the correct thing. Never since have 50% of the respondents mentioned the same. Trust in the government has been completely destroyed.

Both Watergate, as well as the likewise separated political environment of the Clinton impeachment, have added to the present divisive political environment, by paying politicians who demonize their contenders.

A toxic atmosphere of partisanship in the House, as well as the nation more broadly, has caused each of America’s three impeachment crises. Luckily, a spirit of civility and rationalism in the Senate has delivered US democracy from risk every time a president has been impeached –up to this point. To guide the nation through an impeachment crisis, senators, especially, needed to prioritize what is constitutionally right over what might satisfy their constituents. They’ve needed to consider the chaotic politics of a crisis against their duty to maintain the spirit of the Constitution.

Peaceful resolutions of impeachment crises have usually been bipartisan wins. During the impeachment of Johnson, seven senators crossed party lines to make sure that the balance of powers sustained as the Framers wanted it. Their ethical position was politically disastrous: nobody was chosen to the public office ever again.

With the situation of Nixon, a bipartisan group in the House Judiciary Committee known as the Fragile Coalition worked with each other to debate, and eventually advocate for, the president’s impeachment. Also, with the impeachment of Clinton’s, opposing Senators Trent Lott and Tom Daschle worked with each other to keep Senate proceedings civil and honorable – as well as free of the disreputable information that had agitated the House.

To this point, senators encountered with an impeachment have acted soberly, beyond partisan rage, that the Framers would have wished for. All thanks to them, US democracy has endured three impeachment-related constitutional crises. It’s anything but certain that it can endure the fourth impeachment.

Impeachment: An American History by Jeffrey A. Engel, Jon Meacham, Timothy Naftali, Peter Baker Book Review

Framers enshrined Impeachment in the US Constitution as a method for Congress to inspect presidential dishonesty. However, it has been Congress’s choice to read what that signifies at any particular time in history. Every time the danger of impeachment has appeared, it has introduced a constitutional crisis by making bipartisanship a political problem.