In the near future, Holocaust survivors will all be gone. No living person with the recollection that mortals have the capacity of such sinful doings will exist.

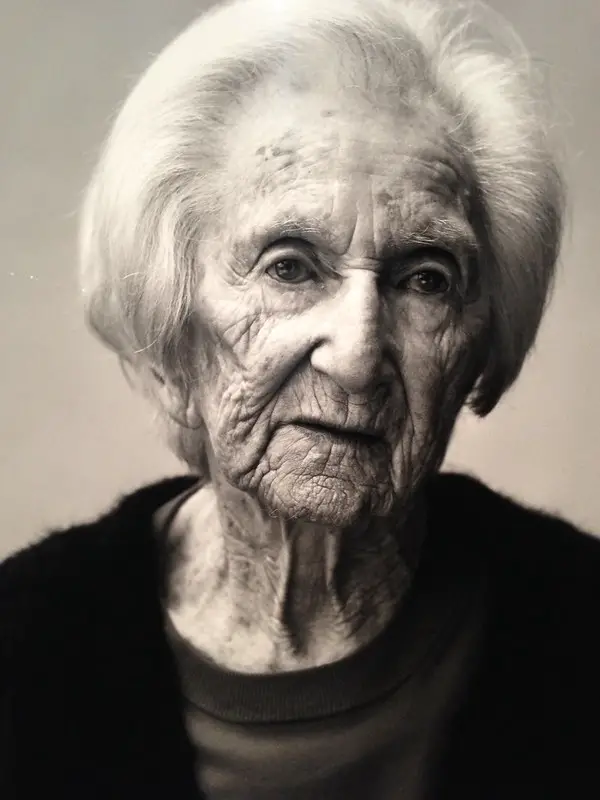

Hédi Fried is among those last survivors. She was transferred to Auschwitz in 1944 and lost many of her folks to the concentration camps, yet she herself was able to survive. Barely.

She is now at her death-bed, while the extreme right-wing nationalism and hatred are rising once more, making us recall how valuable open-mindedness and harmony are. The modern world terrifies her – she’s witnessed all of this previously. Charismatic leaders still provide easy answers to complicated issues, blaming the helpless minorities for everything. An exhausted tale with a terrible conclusion, happening once again.

The terrible conclusion can be averted if we manage to learn our lessons from history. The people who have come face-to-face with such evil would be the ultimate resource for us to take lessons from. Making us recollect the reason why we declare “Never Again”.

This summary will clarify the inquiries you have about the Holocaust: How were the living conditions of the concentration camp for women? How did those who gained their freedom truly feel? Were survivors able to stop resenting the Nazis who imprisoned them?

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks

Chapter 1 – Inequalities should be stopped at the very start.

In 1924 Hédi Fried was born, in a town called Sighet in Romania.

Hédi had a joyful childhood among a big and crowded family and a caring society that supported each other. Sighet was housing people from different backgrounds including Romanians, Hungarians, Christians, and Jews who all lived together.

She began to see that some things were changing as time went on. Her, being a Hungarian Jew, has started to come across hatred increasingly.

In the earliest symptoms of this prejudgement and hatred were intensifying gradually similar to the initial strands of a spider’s web. The number of strands started to increase during the 1930s.

While the war was forming, Hédi’s school presented a question to the pupils: what kind of help they would like to give if a war began. Hédi, welcoming this brand-new trial, wanted to work for the post office. Hédi and her friends went to meet their trainer, who asked them if all of the students were Romanian. Hédi’s hand did not raise while all the other students’ did and she was told that she could not continue the training and was forced to go home crying.

Soon after this event, during the war, the Hungarian army came into Romania along with Hitler’s Nuremberg Laws. In the beginning, the government officials of Jewish descent were fired. Later, the Jewish doctors and lawyers were prohibited from attending to and doing business for non-Jewish people. Jewish shops were no longer serving to non-Jewish people. Next, unfortunately for Hédi, Jewish children were not allowed in schools.

Hédi and her folks were forced to adapt to this unusual life, as these horrible rules were executed one by one. The circle was closing in on them, yet they were sure that this would end. Germany would shortly lose and the war would end.

Unfortunately, one terrible law led to another one that was even worse. The Fried family were made to sew on yellow stars on their attire. Later on, they were prohibited from going out to the streets, to parks, and cinemas. Nevertheless, the family acclimatized to the situation.

Later, the family was removed from their house and put into the city’s Jewish slum. Despite Hédi being forced to leave her dog Bodri, and to say goodbye to her bedroom, piano, and journals, she was still hopeful that this would soon end. She believed that she and her family would one day come to their house again.

After a long while, she understood that the horrible events that were unfolding should’ve been avoided and prevented at the beginning – from that first day she was forced to go home from her school because of her race. Which is what she teaches all of us now: do not, under any condition, get accustomed to inequality.

Chapter 2 – The anti-Semitism in Europe stemmed from three main myths.

While the perils of anti-semitism were closing in on the Fried family, Hédi questioned the reason why copious amounts of people were hating her. Her father described to her fully about the origins of the racism they were up against.

A central Christian lie is the initial and the oldest of these myths.

Christian missionaries that ventured throughout the world to persuade others into Christianity were abundant in the Middle East during the beginning of the religion. However, Jewish people were not keen on becoming Christians and refused Christianity adamantly. After their refusal, they were blamed for killing Jesus. From that point in history, Jewish people were victimized again and again by Christians in a more and more spiteful fashion.

One other myth that originated during the Middle Ages is the malicious blood tale. First heard of in an Eastern European Village. During the first months of the year, a Christian teenager got lost and a Jewish pastry maker was blamed for having killed him to cook Passover bread with his blood. Dishonest testimonies were made against him saying that they witnessed the crime. The villagers came together in mass with clubs on their hands and gathered all the Jewish people in town to oust all of them. Come spring, the ice on the surface of the creek next to the town thawed, and the corpse of the young boy was found drifting on the water. The boy had drowned, he was not killed.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of the poisonous anti-Semitism. Shortly, the myth started to circulate in Europe with other villages making the very groundless allegation that Jewish people were collecting the blood of kids. Countless Jews were killed by these ill-informed people. The latest court case based on this accusation happened as recently as 1883 in Hungary.

The newest of the three myths are a complicated group of deceits that came from Czarist Russia. They were first seen on a pamphlet in 1903 called “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion”. The pamphlet alleged that Jewish people had prominent statuses globally and that during the late 1800s, they had planned a comprehensive strategy to rule the earth. Adolf Hitler also held this lie to be true which kindled his anti-Semitism ahead in time. When the Nazis started to rule Germany in 1933, these Protocols were distributed to kids in schools.

The common point in all of these myths is that all of them are far from the truth. Unfortunately, they all provided a fertile ground for anti-Semitism and the Holocaust.

Chapter 3 – The horrors of the concentration camp were evident as early as the arrival.

It was an unusual spring morning in Sighet on May 15, 1944.

Hungarian gendarmes were gathering the residents of Sighet’s Jewish ghetto as nineteen-year-old Hédi witnessed their arrival.

Many Jewish people, including the Fried family, were put into a vehicle and transported to an unknown place. At the uncomfortable ride’s end, they were told to get off the car. It was nighttime.

Under torch beams, they stood on the ramp before Auschwitz, alongside many other bewildered Jews from across Europe. After a barrage of shrill commands and insults, Hédi was separated from her parents.

She was not able to meet them again.

Shocked at the events that were unfolding, Hédi was keeping her younger sister Livi, who was 14 years old at the time, close. With her parents separated from them, Hédi promised herself that she wouldn’t let them take her sister too. The two were told to wait in a lengthy line.

There, they met Dr.Mengele, who was known for his evil practices on Jewish victims. He was standing there on the entrance to observe the newcomers. He had the power to choose if a person would be able to live and work or die instantly in the gas chambers with a slight snap of his rod.

During that evening, Hédi and her sister were picked for tough manual work. While their parents were transferred to a bathhouse, but at this “shower cabin” what flowed in was not water, rather it was Zyklon B, a deadly gas. Hédi was not even allowed to embrace them before they left.

While the two were in the camp, Hédi and Livi were given old rags and rough shoes and disrobed of their own clothes. They were only given pieces and bits of food to eat.

They came to understand that the reason they were alive was almost purely chance. The SS guardsmen were instructed to act viciously and treat the Jewish people at the camp as subhuman. Whenever they wanted to, they would beat the prisoners and even went as far as to kill many of them. After falling sick because of the conditions, the prisoners were deemed unuseful for work and would be killed off in the gas chambers. Or sent to Dr. Mengele.

The prisoners at the camp were continuously terrorized by Mengele. Sometimes he would come by to choose a fitting “patient” for his operations. He had an obsession with twins, women carrying children, and people with physical abnormalities. After he chose someone, he would act weirdly kind to them or give them candy. He was called the “Angel of Death” by some.

The terrors of the camp left the prisoners unable to tell the course of events. A lot of them were not able to understand whether they have been in Auschwitz for merely hours or for long years.

Chapter 4 – At the concentration camps, the people underwent extreme starvation.

The horrors that overtook the prisoners were only one of the three devastating feelings that they experienced in the concentration camps.

One of those sensations was the cold. Having been undressed by the guards to wear merely old rags, the inmates were struggling to outlast the icy Polish weather.

The other one was the crippling hunger they felt.

Since the Nazis did not expect the inmates to live in the camps for a great amount of time, the meals were not abundant. It was only sufficient enough for a person to live for three months. The meal was only 5 grams of margarine, 300 grams of black bread that was mostly made up of sawdust, and rarely some bits of sausage or a little bit of marmalade. In the evenings, the inmates were given a watery soup of potato skin. They were also given a dark drink to consume the Nazis claimed was “coffee”, and it certainly was not that.

All of the women including Hédi were fighting the growing hunger they faced against more than any other sensation, even the freezing cold. Over the course of their lives in the camp, the starving sensation became a mutual one, the women came together as a sole grumbling stomach.

The inmates were driven to frenzy by their extreme hunger. Hédi has to deceive her belly into believing she was eating by mimicking eating by grinding her teeth. Before she went to sleep, she would think about the bread she would receive for breakfast tomorrow.

Tragically, this starving sensation would cause conflict among women. They would have to argue and fight over the smallest of foods they received. Girls would take food from their parents and sisters would ransack each other’s meals. This misery they felt would lead to the worst and pettiest of arguments and hatred.

Another poor attempt at trying to gain access to food was when women were sent to labor out of the camp, along with the guardsmen. The women would try to get some old vegetables from the farm plots even though they had the chance of being killed on the spot.

During the nights, the women in Hédi’s camp would gather up when the guards left and told each other about the foods they would cook in their houses. Together they would dream that they were all making meals, every one of them producing various ingredients to the counter. To get away from the terrors of the camp, they dreamed of having banquets together.

Chapter 5 – Existing in a concentration camp had particular challenges for a woman.

The Nazi guardsmen that ruled the camps were vicious towards all inmates. Just like men, women were also pushed to have copious amounts of workload and suffering. Additionally, they had to live with more challenges that have frequently been ignored.

The personal possessions including garments were all taken from the inmates that entered the camps. For menstruating women who had no essential hygiene supplies, living in the camps were particularly hard.

With no pads or tampons, they did not have the supplies to restrain the bleeding they were experiencing. For the fortunate few, sometimes the block elder, the woman who was chosen as the ruler of that part of the camp, would provide them a scrap of cloth.

Though, generally, the women were not provided with anything and had to live in blood-stained clothes. To make the matters worse, once they were seen by the Nazi guards in stained clothes, they would be brutally attacked and injured.

Strange enough, some women who came to the camps no longer got their periods while living there. Most probably because they were all distressed and starving. But another factor might have been a particular hormone that was forced onto them by the Nazis designed to stop their periods.

For women who were put into the camps, another terrible event also took place. Brothels were established to keep the spirits among Nazi guardsmen high.

Even though any kind of connection between different races was prohibited by law, the Jewish women who were living in the camps would be transferred to these brothels when they were done with that day’s work. The women would have to obey the commands because if they didn’t, they would be executed. Following a terrible night in the brothels, they would have to go back to their slavish work when the sun came up.

A decorated Nazi officer would sometimes take interest in one of the women that were working in the brothels. That woman would be able to live in his house and had the luck to avoid the harsh workload and the brothel. Nevertheless, these few lucky women also faced the same fate as many did in the camps since they would also be killed sooner or later, because of the senseless system of the Nazis.

Though, Hédi and Livi managed to avoid this physical exploitation and abuse that so many women experienced. They were always clinging on to each other like conjoined twins which let them survive the SS Guards’ terrible system that tortured so many people. They were each other’s motivation to continue living.

Chapter 6 – With loads of people trying to get to their houses that were destroyed, the direct consequences of the Holocaust were at the very least tumultuous.

Hédi and her sister were sent off to Bergen-Belsen, another work camp in the north of Germany in April of 1945.

The British 11th Armoured Division found the camp’s famished prisoners and thousands of unburied dead bodies when they freed the camp two months later.

Starving, sick, and traumatized by their experiences, most of the prisoners had difficulty understanding “liberation”. After what they had experienced, what sort of life would they live now?

Hédi encountered the first moments of her freedom in a fever dream.

During the turmoil after the liberation, she desperately looked for her father in a closeby camp. While she was there, at her weakest, she came down with typhus and a bad fever. She blacked out after a short while. She gained her consciousness two weeks later, with Livi near her bed in an asylum. Without her sister’s undying love and care, it would be impossible for her to get better.

Before she gained her freedom, Hédi thought that she would be able to go on as she did previously. She would go back to Sighet to go after her goals. Go to university, become a pediatrician, and visit Africa to help others.

In reality, Sighet was not the same as before. Soon after, she and her sister would travel to Sweden on an ambulance boat, where they would live until their last days. Things would not go back to the way they were.

Still, countless survivors sought to go back to their homes.

Unfortunately, Europe had been tarnished by the war and there were no ways to travel easily among countries. Most survivors of the camp tried to walk, hitch rides or get on trains if they saw them. Thousands of Jewish refugees were wandering across Europe.

Out of the 31 people in Hédi’s family, only ten people survived the concentration camps. And fewer of them tried to return to their homes.

Her uncle Sanyi was one of the surviving relatives she has. Through working in a bakery in Auschwitz, he supported himself on bread. Sanyi looked for his wife Helen frantically after being liberated. He believed that if his wife did survive, she would return to Sighet, thus he got on the lengthy road to his city on foot.

Once he came to Prague, a miraculous thing occurred. While he was wandering around in the streets, he saw his beloved Helen. She had also thought the same. Can you even begin to comprehend what was going in their brains when they saw each other once more?

Chapter 7 – The issue of identity had become a difficult problem for Holocaust survivors.

Hédi had first encountered questions about her identity even before the war had started.

Hédi thought that her nationality was Romanian while living in Sighet, Romania, as a Hungarian Jew. When she started to live in Sweden in the post-war era, she believed herself to be Swedish. Still, she was never certain of her identity.

Before the war, Hédi began to notice these questions for the first time.

During her childhood, her friends that she played with all came from different backgrounds and religions, and she had not really given that much thought to their differences. They all had unique clothes, were able to speak different languages, and had different foods and she considered them all to be an essential component of her youth. She saw them as just kids; her play friends. Their races/religions, Romani, Christian, Romanian, Hungarian or Jewish was not of importance.

She was not conscious of the ethnic or national diversity of the town until she started going to school. The students were prohibited from speaking any other language other than Romanian and were even penalized for doing so. Hédi, on her first day there, because of speaking Hungarian, had gotten a few beats with a cane. The school’s aim was to create one Romanian group out of all the children from different backgrounds. Hédi was now made aware that being different was not admissible.

Later in life, when she was living in Sweden after the war, she had different issues with her identity. Being treated as subhuman by the SS Men, Hédi now wanted to feel accepted by the people of her asylum country. Which did happen at the beginning, the Swedish people did accept her. In the Swedish community, people were sympathetic towards survivors like Hédi.

The old issues showed themselves again after a while. When the initial pity of the Swedish people died down, Hédi once again faced hatred. Yes, the war had ended, and she was now living in Sweden but anti-Semites still existed. Even neo-Nazis were present. She had gotten angry mails from far-right extremists, even from ones in prison.

Another problematic issue was citizenship. In Sweden, after being married, Hédi mothered three children. She had devoted her time and worked as much as she could with her husband for Sweden. But to be granted citizenship and be considered officially Swedish, she had to wait for seven years. Even after gaining her citizenship, she was not welcome among Swedish people that were looking at her meaningfully as if to say: You’re not actually Swedish.

At the end of the day, Hédi Fried is a survivor, no matter the state she is living in, no matter the identities she has gathered from numerous cultures.

Chapter 8 – Permanent resentment was deemed impossible by the Holocaust survivors even though they did feel a rational hatred towards the Nazis.

What would you feel against the murderers of your own kin?

What would you feel against the people who captured you, let you perish, overworked, and damaged you to the point of insanity?

Hédi’s passionate hate began to grow towards the German people who had kidnapped her and the Hungarian people who gave her to them.

An event that almost made her lose her mind happened while she was working outside of the camp. She and her inmates all had worn-out shoes, and they had heard that cargo might bring them new ones. The women working alongside her were all famished and freezing and their feet were all wet in old clogs. Hédi asked the camp chief whether she could receive new shoes.

Before hitting Hédi’s cheek so strong that her ears started to buzz, he menacingly grinned at her. After that, he hit her other cheek which made Hédi fall to the ground with agony. At that moment, Hédi thought that she could murder him with no hesitation, but she did manage to hold herself down. Though she did resent him, with her whole being.

Though, Hédi’s resentment towards the Hungarian gendarmes in Sighet that had given her family to the Nazis was even more. She was not able to forget their feathered hats for a long time.

But in the end, Hédi recognized that hatred was the ammunition for all of these tragic events.

She did understand that her resentment was justifiable. But she also understood that after the Holocaust, as years went by, her hatred was only consuming her. The feeling of resentment does nothing for the ones that are being resented but affects the person who resents a whole lot. But, if one does act with hatred in their mind, they then become one of the people they hated. Thus, the petty cycle churns.

Most of the inmates understood how devastating resentment was even in the first moments of their freedom even when they felt the urge to seek vengeance the most. When Bergen-Belsen was liberated, the British gathered the Nazi guardsmen in a car and drove them about, yelling: “Here are your torturers, act as you wish, seek your vengeance.” Almost all inmates just walked away, satisfied with just being free at last.

Chapter 9 – The saying “Never Again” is empty without us being very careful.

The saying “Never Again” is still popular even after the 75 years that have passed since the Holocaust. It is a warning that the wickedness of the 1930s and 40s should never occur again. Though, since the survivors are now going down in number, the meaning of the slogan has become watered down with time.

The events that took place could simply occur again?

Genocide has since occurred again. In 1994, almost a million people were murdered in a massacre in Rwanda by Hutu radicals. Again in Serbia, in the 1990s, the Serbian army has killed thousands of Kosovan Albanians and many more.

With forced migration, because of conflict, lack of resources and, global warming, from Africa to the Mediterranean, we see the people that are left to die by the European governments. The carelessness and the apathy of yesterday can easily pass down to today.

While the extreme right-wing nationalism is on the rise once again, we shall be wary of our history with more caution. The advancement of anti-immigrant politics should make us remember the events that took place in the 1930s and the 40s are not so distant from now.

Hédi Fried claims that the most efficient way to advise against what has happened in our history is through teaching in a way that is for both the mind and the heart. It is true that if information only goes through our minds, it is quickly forgotten. For us to internalize our knowledge, it should create an emotional reaction in us. It has actually become apparent that we can learn some things only with our feelings.

She thinks that to achieve this, we should teach the narratives and testimonies of the survivors. When we tell the tales of intimate grief and death, she thinks that the contemporaries can internalize the teaching. Which is, Never Again.

And lastly, we should avoid just standing by and doing nothing. The unfortunate thing is, the type of people that lived in the 1930s and 40s still exist today. In any school playground, we can see the bullies, the victims, and the bystanders. The exact thing applies to the whole society. To quote Edmund Burke, a liberal philosopher: it just takes a lot of humans to do nothing for darkness to spread.

To take down the darkness, we should understand when to intrude. In countless sections of the earth, that time has come.

Questions I Am Asked About the Holocaust by Hédi Fried Book Review

The anti-Semitism that gave the Holocaust a fertile ground has grown gradually, year by year. When it started to happen, it was too late to intervene. The victims of the Holocaust were treated as subhumans while it happened. Women and men all got the same brutal treatment but women did suffer some particular adversaries and trials. During the turmoil that followed the freedom of the victims a lot of survivors were unsettled and adrift. Most of them had issues with their identity in their asylum states. Now, we are once again face-to-face with growing hatred and nationalism that must be fought against if we want to prevent the replication of the terrors of history.

Stop your own prejudices early on.

Stop yourself if you ever realize that you are stereotyping a group of people with your friends or your colleagues, whether it is because of their sexuality, gender, ethnicity, or nationality. While these may appear inoffensive to you personally, think for a second on how hatred stems and grows. Similar to this. From people similar to you, believing that they are just messing around.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks