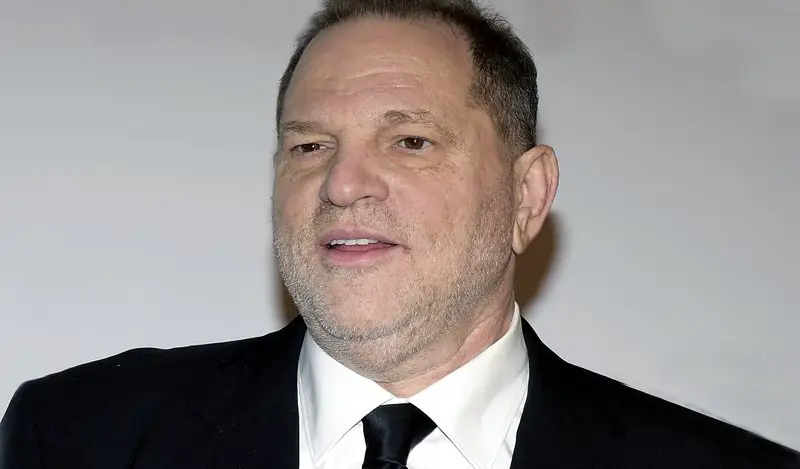

For decades, Harvey Weinstein was the highpoint of Hollywood success for long decades: a well-known producer of famous films and winner of numerous awards, his impact extended across the industry. But, behind this charm, was a dark reoccurrence of abuse, exploitation as well as sexual harassment. It needed the bold reporting of two investigative journalists to expose the actual face of this movie tycoon.

This book summary exposes the story behind the headlines, from the viewpoint of the journalists who exposed the news. You’ll find out how months of interviews and detective reporting changed rumors and accusations into a global movement that couldn’t be held back. This stirring disclosure piles together stories of courageous actresses, dubious legal transactions and a Supreme Court battle, into an enthralling account of the #MeToo period.

Chapter 1 – The investigation into Harvey Weinstein started with just an email conversation.

May of 2017, the investigation started with a hesitant email exchange between New York Times investigative reporter named Jodi Kantor and an actress Rose McGowan.

Top film and television actress McGowan was famous for her outspoken Twitter feed detailing daily sexism in the media industry. Kantor, who had worked at the Times for 14 years, had a trail record of writing gender discrimination at key firms such as Starbucks and Amazon.

McGowan had lately tweeted about her personal rape story by a Hollywood producer. She didn’t say their names; however, rumors have it that the culprit was the media tycoon, Harvey Weinstein. Weinstein, an industry powerhouse, was famous for transforming young talents, like Gwyneth Paltrow, Michelle Williams, and Jennifer Lawrence, into superstars. Also, he has political influence, raising money for well-known Democrats, as well as Hillary Clinton.

Initially with reluctance, McGowan explained her complete story to Kantor; however, it was just off-the-record. The information she gave was outrageous. According to McGowan, she came across Weinstein in 1997 during the Sundance Film Festival, where he had invited her to his hotel room saying they were going to talk about business. After a short exchange in the room, he forced himself on her without seeking her approval. Terrified and surprised, McGowan was powerless and couldn’t escape.

After a few days, McGowan got a message from the producer, insinuating that both of them could have a special agreement. Offended with the bid, the actress employed a lawyer, who got a $100,000 settlement from Weinstein provided that the issue would be kept as a secret.

Kantor had no cause to be suspicious about the story; however, such fiery accusations would have to be validated, or else, the case could easily end up being a situation of “he said, she said.” Having this in mind, she asked for the advice of Rebecca Corbett who is her editor, who advised that she investigate further before publishing anything.

Also, Corbett advised that she asked the assistance of one of the Times’s latest reporters, Megan Twohey. Twohey, who became part of the reporters in February 2016, had already caused disturbance writing on several sexual assault accusations against the then-presidential runner, Donald Trump. The reporting had started a media circus, and a lot of the women she interviewed faced harassment for speaking out.

Twohey was on maternity leave when Kantor called her, and the two reporters talked about the issue ahead. If they collaborated, perhaps they could find a manner to reveal the prevalent harassment experienced by a lot of women and the system that protected the influential men that committed it.

Chapter 2 – Kantor and Twohey discovered a lot of victims; however, no one was ready to go on-the-record.

June of 2017, Jodi Kantor started verifying Rose McGowan’s story by looking for other women who’d had faced the same experiences with Weinstein. The sensitive issue made the investigation hard even for the experienced reporter.

The first difficulty was finding and talking to the actresses who had worked with Weinstein. The usual method would be to contact their publicists or managers; however, these gatekeepers were more concerned with keeping their clients’ reputations or that of Weinstein himself. Another method was to contact previous Weinstein workers; however, this too, regularly was futile. Some people said that Weinstein’s deeds were a “non-story,” only business as normal in Hollywood.

Finally, Kantor made a few contacts, as well as actresses Marisa Tomei and Daryl Hannah. Although none of the women had direct experiences with Weinstein, they were ready to talk about the abuses they had experienced in the industry. In spite of them being greatly successful stars though, they also felt weak to talk and were concerned about possible consequences. A few weeks later after following leads, Kantor got another big break, scheduling a FaceTime interview with actress Ashley Judd.

Judd, who studied gender violence at the University of Kentucky, was open about telling her story. She described that back then in 1996, Weinstein had invited her to his hotel for what he again said would be about business. But, when she got there, the producer opened the door wearing just a robe. During the experience, he made a lot of belittling requests in an increasingly aggressive way. Judd remembered feeling stuck as if any resistance would lead to the end of her career. She succeeded to escape by cracking jokes and getting out through the door.

For Judd, the event was disturbing, however more disturbing was the habit. It looked like Weinstein had a pattern of making unwanted sexual advances on women with the indirect threat that their careers were at risk. The only approach to stop him was to look for more previous victims. Having this in mind, she decided to assist Kantor with the investigation, making contact with other actresses – first was Salma Hayek, then Jenni Konner and Lena Dunham, and finally Weinstein’s top star, Gwyneth Paltrow.

When Kantor spoke with Paltrow, the stories were similar: an invitation to a hotel, inappropriate sexual advances, then bad-tempered and dismissive treatment when he was rejected. Paltrow had first attempted to forget about the event; however, now she was prepared to assist in looking for other victims.

August of 2017, Kantor and Twohey had seen and interviewed a lot of women; however, none of them, even Paltrow or Judd, felt secured enough to go on the record. The way forward was to look for solid evidence.

Chapter 3 – Kantor and Twohey sensed that a lot of Weinstein’s victims were made to keep quiet by stern confidentiality agreements.

Kantor and Twohey were at a dead end – Weinstein had obviously abused a lot of women, however, none felt secured enough to go on-the-record. To carry on with the investigation, they had to follow other avenues.

Twohey needed solid evidence. She thought that, with Weinstein’s serial offenses, there might be public records on his deeds. With the assistance of Grace Ashford, a young researcher at the Times, she trailed down a report from California’s Department of Fair Employment and Housing. The report made a reference at occurrences at Weinstein’s company, Miramax; however, the paperwork was futile. Another dead end.

If Miramax workers were issuing complaints, why were there any records? Twohey’s colleagues at the Times provided a likely justification: confidentiality agreements. Although sexual harassment is a defilement of federal civil rights laws, it’s not a criminal offense. Hence, companies can resolve complaints out of court by paying cash– however, these regularly come with conditions. Women are forced to turn over their entire evidence and accept not to ever talk about their complaint again, not to even friends and particularly not to journalists. By doing this, abusers can purchase their victims’ silence.

The next question was clear: had Miramax made Weinstein’s victims sign those kinds of agreements? Through working their contacts, Kantor and Twohey discovered numerous previous workers of Miramax, all of which were young women, who had left the company unexpectedly and under strange situations. The journalists went to extra miles to meet each of them, even in their houses. While considerate of the reporters’ mission, all of them refused to talk. Was their silence as a result of confidentiality agreements?

Eventually, a woman named Zelda Perkins proved Kantor and Twohey’s suspicions. Perkins worked for Weinstein during the mid-90s. Initially, she and her colleague, Rowena Chiu, lived with Weinstein’s wrong advances; however, after certain aggressive experiences at the Venice Film Festival, they employed lawyers and laid complaints. The two of them fought hard, however, eventually, Miramax’s powerful legal team intimidated both of them into taking a settlement with a really stern confidentiality agreement involved.

In spite of the possible repercussions, Perkins was interested to come forward – on-the-record – and defile her agreement. But Kantor had another source to interview: an Irish woman called Laura Madden. Back then in 1992, Madden had her own disturbing encounter with Weinstein while she was working as a production assistant in his film, Into the West. Her encounter followed Weinstein’s normal habit, but for one main difference: Madden never accepted or signed any agreement. She was free to say her story.

Chapter 4 – Weinstein hired a big team to disrupt and disrepute Kantor and Twohey’s investigation.

On the 12th of July, Kantor and Twohey saw Dean Baquet, the executive editor of the Times. He was fascinated with their work; however, told the team to be careful while they continue. Weinstein would aggressively protect his reputation – both reporters should believe that they were being followed, and none should speak to Weinstein off-the-record.

Baquet’s guess was right. A few weeks later, Lanny Davis, a high-powered attorney and one of Weinstein’s close associates, made a contact to the Times. He sought to see the reporters; however only on background, signifying that the journalists could report what he told them, however they shouldn’t mention his name. Putting aside their doubt, Kantor, and Twohey, and their editor, Rebecca Corbett, decided to meet him.

On the 3rd of August, the gamble was worth it. During the meeting, Davis exposed some significant information. He accepted that Weinstein had truly settled with Rose McGowan, providing vital validation to the star’s story. Also, he admitted that Weinstein knew about the investigation; however, had no intention to interfere. But, this showed to be far from the truth.

As a matter of fact, Weinstein wanted to crush the investigation by any means possible. In order to do so, he recruited the assistance of David Boies, a lawyer extremely entangled in Weinstein’s businesses. Boies had published a journal through Miramax Books and Regency, his daughter, had been cast in Miramax films. Also, in 2002, he had succeeded to keep the New Yorker from doing a similar investigation into Weinstein’s abuses. If anyone could assist in destroying the story, it was Boies.

In July of 2017, Boies assisted Weinstein to employ Black Cube, a suspicious private firm operated by former Israeli intelligence agents. The firm had already assisted Weinstein spy on McGowan, influencing her into sharing the memoir that she had not yet published. Now their job would be to hinder Kantor and Twohey. Black Cube’s agents started monitoring the reporters, trying to know what they knew already.

Aside from his military-grade team of spies, Weinstein also had another powerful associate: lawyer Lisa Bloom, daughter of a respected and controversial attorney, Gloria Allred. Bloom was held back by Weinstein in December 2016, who has assisted with all part of the producer’s defense strategy since then. After, Kantor and Twohey would get a memo she wrote to Weinstein. It had comprehensive plans on how to slow the investigation, disrepute Weinstein’s victims, and make the producer appear like a changed man.

Chapter 5 – Weinstein’s business associates were ready to cooperate just to save their company from Weinstein’s irresponsible act.

In September of 2017, Kantor and Twohey had difficulty. They had collected a lot of evidence against Weinstein, however, not enough to publish. In order for the investigation to progress, the team required information from Weinstein’s business associates. But, these officials were more worried about protecting their company than assisting the defenseless women – at least initially.

Accidentally, one senior executive named Irwin Reiter was cooperating: a Weinstein Company accountant. Reiter had done Weinstein’s books from the 1989 and detested the producer. In a lot of meetings with Kantor, he contributed his view on the case: Why was the Times really concentrated on incidences from the 90s when there were a lot of latest problems? Also, there was the chance that Weinstein misused company money to fund his irresponsible behaviors. Reiter was sickened on how Weinstein handled women; however, he was also angry that his actions will put the company in danger.

Apparently, Bob, Weinstein’s brother, felt the exact way. The brothers were close one time; however, a decade of business disputes and violent personal conflicts had made them separated. Bob got fed up in 2015. Working closely with Reiter and board member Lance Maerov, he attempted to limit Harvey’s behaviors with a new contract that had firm consequences for unpleasant acts. Also, Bob requested that his brother get professional help for sex addiction.

During that same year, Bob wrote a harsh letter to his brother; however a genuine one. He talked about the pain Harvey’s behaviors had led to and pleaded with him to change. He wrote in the letter that “You have brought shame to the family as well as your company through your misconduct.” Still, even then, Bob was majorly worried about guarding the company, and therefore little changed.

After combining information from company insiders together, Kantor and Twohey published their first story on Weinstein during late September. The article was entirely on financial issues. In 2015, Weinstein had a fundraiser for an AIDS charity and eventually channeling $600,000 back to his own investors – a likely situation of fraud. The article was an alert to some: Weinstein was actually turning to a liability.

Reiter understood that he had to do something, and succeeded to get an important piece of evidence concealed in Weinstein’s personnel file. It was a memo written by a previous junior executive named Lauren O’Connor. The date on it was 3rd of November, 2015; the file had comprehensive information on Weinstein’s habit of abuse and cover-ups. It was what Kantor and Twohey required. That night, Reiter gave it to them.

Chapter 6 – The memo of O’Connor’s commenced a hectic few days of work at the Times.

Friday the 29th of September 2017. With O’Connor’s critical memo in hands of Kantor and Twohey, they were eventually prepared to write. Writing the story signified writing down all the last fact, conducting on-the-record interviews, and lastly, getting in touch with Weinstein for his reply. The next few after would be difficult.

The two reporters evaluated what they had: ten reliable stories of sexual misconduct dating from the years 1990 to 2015. These, plus O’Connor’s memo and an on-the-record interview with the Irish production assistant Laura Madden would be the pillar of their story. It was a persuasive story, and probably really strong to make extra sources go on the record. Having this aim in mind, Twohey and Kantor started to work.

The job was discouraging. In fast progression they got in touch with the entire main players: O’Connor, the author of the memo; Maerov, the board member who, together with Bob, had attempted to control Weinstein ; John Schmidt, a previous Miramax executive concerned to their cause; and eventually, McGowan, the actress who had started the investigation. Each refused to go on-the-record. Also, Madden, their main source, was getting scared. But, Ashley Judd, still extremely worried about future victims, seemed interested. She only wanted a few days to think things through.

Nevertheless, on the 2nd of October, a draft was complete and it was time to get Weinstein’s reply. The interview would be heated. Kantor and Twohey had to disclose what they knew already – Weinstein could verify the information or just use the information to lash out at their sources. Also, there was the question of the time the Times should give the producer to reply. If it is too short, he could claim dishonesty and if it is too long, he could attempt to destroy the story.

The next day, Kantor, Twohey, and Corbett talked to Weinstein over the phone. The producer called in with his normal legal team, with Charles Harder, a no-nonsense attorney famous for suing media outlets for defamation. The interview was tensed. Weinstein was bad-tempered and kept requesting information on sources. Also, he threatened to take his issue to other, friendlier media outlets, a move that would undermine the influence of the Times’s scoop.

After the call with the reporters, Weinstein was offered 48 hours to reply. While Kantor and Twohey were waiting, they got a call from Judd. She had made her choice and was ready to speak. The story of her disturbing hotel room experience with Weinstein would be the lead.

Chapter 7 – After resisting last-minute legal threats from Weinstein, Kantor and Twohey’s sensitive article got to the press.

On the 4th of October, 2017. With the 1 p.m. publication deadline with just hours let, Kantor and Twohey, contacted Weinstein’s lawyers to tell them that Judd’s story would be included in the article. Again, they pushed for an official reply. However, the producer’s team intended to make the process as slow as they could.

Eventually, at 1:43 p.m. an email came in. It had an 18-page diatribe written by Harder, Weinstein’s most aggressive attorney. The lawyer denied everything in those pages he sent and labeled Weinstein’s accusers as bitter, manipulative liars. Also, he criticized the Times itself, claiming that, by giving really little time for a reply, the paper was deserting its journalistic principles. It concluded with a threat to take legal action against the paper for millions in damages.

That type of bold language was intimidating. But, legal experts at the Times guaranteed Kantor and Twohey it was only that: tough talk. Harder’s threats wouldn’t get to court. Yet, the investigators decided to wait a bit on the deadline one last time. The story would get out at 1 p.m. the next day, with or without Weinstein’s reply.

Still, the Times had no official statement from Weinstein the following day. As the deadline approached, Kantor and Twohey picked up a lot of last-minute phone calls from Weinstein and his lawyers. The discussion headed nowhere. Not until the paper’s executive editor, Baquet, came in, that Weinstein sent an official report.

After all the accumulation, the reply was mostly confused and rambling. The only new detail they got was that Weinstein would go on a leave of absence from his company. The draft was modified, and within minutes it was all set to go. At 2:05 p.m., the article was published online by Baquet. The headline was straight and easy: “Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades.”

The reply was direct. The Weinstein Company was sent into confusion. They held Emergency meetings. Board members quit. Weinstein tried damage control, working with Bloom on a PR push touting the producer’s regret and apology. The boards were aware that it was finished. Bob Weinstein said to him: “You are finished, Harvey.”

However, the outcome for Kantor and Twohey was really different. The article had created the floodgates. On the 6th of October, the investigators were flooded with calls from several women wanting to share their own stories of their experiences with Weinstein. A lot of former workers came forward, together with further actresses like Rosanna Arquette, Angelina Jolie, and Gwyneth Paltrow and they all wished to go on-the-record. This first article was only the start.

Chapter 8 – The Weinstein story spread #MeToo, an international discussion on sexual assault that got to the Supreme Court.

After Kantor and Twohey’s article entered in the Times, Weinstein had to face actual penalties. The producer was known with sexual assault and was criminally charged for two cases of abuse. But, the actual effect of the investigation reached far above the Weinstein Company boardroom.

The Weinstein story initiated a national discussion on sexual harassment and assault. As women saw that a powerful man was being held liable, it looked like their own accusations would be taken extremely. The hashtag #MeToo, initially invented by a civil rights activist named Tarana Burke, became popular on social media as women talked about their experiences. Celebrities all over industries were recognized as abusers – comedian Louis C.K., Senator Al Franken, and chef Mario Batali all faced inspection.

#MeToo was a complete transformation; however, the movement had critics. Media outlets keen to break the following case published stories with less inspection, sometimes depending on unreliable sources. Also, the concentration on high-profile abusers disregarded the really vulnerable women. An additional story by Kantor and Twohey about Kim Lawson, a young McDonald’s worker, was unsuccessful to achieve much power. Although people were prepared to tackle sexual assault, there was no agreement on how, or even on what tallied as assault.

These questions were close to becoming really significant. During early August, Kantor got a message from Debra Katz, an attorney focusing on gender discrimination. Katz’s new client, Christine Blasey Ford a psychology professor, had a really extreme #MeToo story. Ford said that she was assaulted while at a party in 1982 by two prep schoolboys. One of these boys was Brett Kavanaugh, a high-ranking judge alleged to be President Trump’s next selection for the Supreme Court.

Ford didn’t want her assault – a violent incident that had initiated her decades of anxiety – to be the focus of a national news story. However, when she knew that Kavanaugh might be selected to the Supreme Court, she felt a responsibility to act. During that summer, Ford communicated with her congressional representative and the Washington Post and ultimately wrote an in-depth letter to Senator Dianne Feinstein, the senior Democrat on the Judiciary Committee.

Supreme Court nomination fights are extremely combative, and Ford’s story would only increase the heat. When Ford eventually made her way to Katz, she was unsure if she was ready to face the limelight. Although Ford had some evidence – she passed a polygraph test and had therapy notes explaining the event– it was uncertain what the result would turn out to be. With the hearings planned to start on the 4th of September, Ford communicated with Feinstein to remove her testimony.

Chapter 9 – Ford provided strong testimony to the Senate; however, that couldn’t end the Kavanaugh nomination.

During that fall, Ford attempted to forget about the occurrence; however, the Pandora’s box she’d released by writing to Senator Feinstein could not be shut. Word began to spread about likely accusations against Kavanaugh, and on the 16th of September, Ford’s identity was exposed in the Washington Post. Now Ford had to decide: would she testify against the judge or not?

The odds were extremely high. The #MeToo movement was still trending, and a lot of women and activists saw the Supreme Court nomination process as its greatest significant test. Conversely, Republican lawmakers were resolute to confirm Kavanaugh. As both sides combined support and criticized each other in the media, Katz and her partners discussed the terms of Ford’s testimony with the Judiciary Committee. But, Ford was still unsure if she would come to Washington.

With the hearings scheduled to start on the 27th of September, she had to think fast. She had motives for withdrawing: the professor was getting death threats from Kavanaugh supporters and the President had ridiculed her story in tweets and at rallies. Also, she was scared of flying which made a trip to DC discouraging. Experiencing all this, Ford decided: she would go and testify.

The hearings were done in a tiny room on Capitol Hill; however, outside the entire nation was seeing it. Ford started by reading a comprehensive, accurately-articulated statement talking about her traumatizing experience. She then sat through hours of back-and-forth questioning picking apart all part of her story. All through the trial, she kept a calm manner perfected through years of scientific presentations.

In opposition, Kavanaugh took the stand filled with self-righteous rage. Supported by similarly outraged grandstanding from Republican colleagues, the judge set himself as a victim, the target of unproven slurs invented by an unruly mob. When the hearings were finished, the nomination was ready; however, one thing was sure: everyone – from pundits and politicians to average Americans – would have a choice.

Eventually, Kavanaugh’s nomination was successful. In spite of the power and reliability of Ford’s testimony, it couldn’t prevent Republicans from placing another right-wing justice to the Court. Did this signify that the #MeToo movement had been unsuccessful?

Not completely. That Ford could even speak was evidence of how much things had transformed. The movement remained outside of Washington. Women continued voicing out and perpetrators, from high-ranking CEOs to ordinary abusers, were being held liable.

Chapter 10 – January of 2019, Kantor and Twohey assembled a lot of women at the heart of the #MeToo movement for one last interview.

Years after the publication of their revolutionary article on Weinstein’s abuse, Kantor and Twohey kept on writing stories on sexual harassment and abuse. By January of 2019, it was time to check back on the personal effect of their work. The two reporters organized an exceptional group interview with the women that had become the public face of the #MeToo movement.

For this story, 12 women assembled at Gwyneth Paltrow’s mansion in the Hamptons. Each of them had been affected by sexual abuse, and a lot had offered to say their stories. Among them were Weinstein accusers Ashley Judd, Zelda Perkins, and Laura Madden; Kim Lawson, the McDonald’s employee outlined in following articles; and Rachel Crooks, who had publicized about being kissed by President Trump forcefully.

During the course of the evening and the next day, they talked about their experiences. They talked about the pain of their abuse, their fear about speaking up and the stressful effect that accompanied the publicity.

For a lot of women, the process had cause huge changes. After speaking up, Judd had taken a teaching job at Harvard and became part of the board of Time’s Up, an organization that promotes workplace protections. Lawson now ran worker demonstrations and issued official complaints against her employer with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Crooks dedicated her energy to politics and competed for a position in the state legislature.

As the women talked about each other stories and reached out support to one other, one of the attendees listened with a specific interest. Her name Rowena Chiu, Perkins’ coworker at Miramax, who had initially decided not to be mentioned in Kantor and Twohey’s writing on Weinstein. During her discussion with the other women, she thought of her decision again – perhaps it was time to go public with her own encounter.

She considered the option, sharing her doubt with the group. Each and everyone gave her a bit of advice. Some talked of the power and relief of sharing, others advised her about the nervousness and fear that comes with being in the spotlight.

Eventually, it was Chiu’s decision to make. Madden, the easy-spoken Irish woman who was the first person to go on-the-record about Weinstein, provided the last thought and she said: “There is never going to be an end.” “The key is that people need to keep speaking up and not being scared.”

She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement by Jodi Kantor, Megan Twohey Book Review

It is not easy publishing stories on sexual abuse. Writing on Harvey Weinstein’s three decades of sexual misbehavior was a huge work of investigative journalism. Kantor and Twohey, as well as their colleagues at the Times and other allies, used months pursuing sources, combining the proof together, and doing nervous, emotional interviews. Eventually, their efforts assisted to transform how a mainstream culture deals with sexual abuse.