One question that has stayed close to musical experts and scholars, is if a piece of music can occur on its own, different from the time and setting from which it originates. Maybe one of the perfect instances of this question is the work of a German composer known as Richard Wagner who died in the year 1883. Wagner left his anti-Semitic writing behind; also, his musical works were as well praised by Adolf Hitler as the pinnacle of music.

Furthermore, Wagner was as well praised as a genius by a lot of music critics of his era and demonstrated to be hugely famous with the average listener, and hence his shadow appeared imminent over music during the start of the twentieth century. You’ll find out that, the development of music from extravagant Wagner operas to the minimalist sounds of Steve Reich is as well the history of what was going on around these composers during that period. As politics became more very separated and wars raged, the sound of present-day music shows these transformations and gives the account of people reckoning with their history and trying to plan a way forward.

Chapter 1 – Contemporary classical music took a brave move forward with the effort of Johann Strauss under the great shadow of Wagner.

During the start of the twentieth century, the lovers of music all across Europe were still under the charm of Richard Wagner. By the year 1900, the composer had already been dead for more than 15 years; however, his performances had been really extravagant and magnificent that they’d turn to the height of entertainment.

In the year 1876, when Wagner debuted his four-part opera series called the Ring cycle in Bayreuth, Germany, royalty and the upper class of culture from all across Europe were present, as well as other composers like Tchaikovsky and Franz Liszt. The occasion was really an amazing one that the New York Times did stories on it for several days. During the time of Wagner’s, he was basically the blockbuster producer of then.

The following age of composers, who were attaining their maximum level of competence at the beginning of the new century, had developed under Wagner’s significant guidance. This comprised giants of Austro-German music like Gustav Mahler as well as Richard Strauss.

Strauss can be considered as the main voice in making the music that was to happen in the track of Wagner’s lavish and wealthy work. The work of Strauss in the year 1896, Consequently Spake Zarathustra, basically declares new start coming, the music growing and glowing as it makes use of the natural harmonic series.

Trumpets play C, G, and also a higher C; the breaks between the notes correspond to normal proportions on the frequency spectrum and hence sound appealing to the ears. If you’ve watched the film 2001, titled A Space Odyssey, you’ll identify these “rising” notes instantly; during the first scene of the movie, they’re remarkably made use of to herald a new start for human.

On the 16th of May 1906, the new operatic work of Strauss, Salome was done in Graz, Austria, and it heralded a new way. Just like Zarathustra, Salome gets the listener from the start; however, this time the selection of notes, as well as progressions, is utilized to a totally different end. In just the first few seconds, the listener is constrained to a range that begins in C-sharp major; however, immediately moves to G-major – a totally different key, bringing about instant dissonance. Also, this fast change comprises the interval of a tritone, also referred to as Diabolus in musica, or “the devil in music” by among music experts.

The ears of human don’t react perfectly to the tritone because it juxtaposes two really different harmonic spheres. Due to Strauss’s abundant use of those kinds of dissonances – musical instruments that don’t follow the traditional musical harmony – Salome was welcomed with a surprise that was either of as a result of enjoyment or revulsion, reliant on the person.

Chapter 2 – The Sixth Symphony of Mahler moved towards the avant-garde in a different way than Strauss’s Salome.

A lot of big figures, like Puccini and Mahler, were there when Salome did his performance at the Graz. However, the rising composer known as Arnold Schoenberg attended as well together with six of his ardent pupils and Alban Berg. Afterward, Schoenberg, as well as Berg, became famous and extremely significant forces in what was referred to as the Second Viennese School of classical music.

Mahler and Strauss were somewhat close friends during the beginning of 1906. However, although Mahler was fascinated with Salome, his own key work – his Sixth Symphony – premiered in the German town of Essen only eleven days after, on the 27th of May. In his work, Mahler tries to push his limits, too. The first movement comes in the traditional sonata style; however, it has two opposing musical themes that ultimately combine. The last fourth movement intensifies the concept of opposing themes, with gushing waves of happy fanfare battling chilling, militaristic marching beats.

All these forms various huge “hammer-blows,” which at the premier encompassed of a meter as well as a half drumhead being hit by a huge mallet. However, the last shock is kept for the ending – when the last movement seems to have hitched to a finale, a very loud A-minor chord comes in just like a metal crash.

Certainly, after the final practice, Strauss teasingly said to Mahler that the performance had made the mayor of Essen die as a result of a heart attack. However, what was more important to Mahler was that Strauss had just a thing to mention about the symphony, and that was he noticed the last movement to be “over-instrumented.” Their friendship became complicated after the performances of May 1906.

Both Mahler and Strauss were usually jealous of each other, Strauss getting jealous of Mahler’s popularity and Mahler getting jealous of Strauss’s reputation among the other composers as an interesting artist. During that period, there were concepts already that what was famous with the entire public was barely the type of cutting-edge art that would remain popular for a long time. But, in the situation of Salome, Strauss’s opera was both a bestseller with listeners and the type of work that new composers were happily talking about in cafes.

As composer Alban Berg said of Salome, “Never were the box office and avant-garde really well acquainted.” However, the dissonance in Salome would seem less important compared to what Arnold Schoenberg, the mentor of Berg had prepared.

Chapter 3 – Together with Schoenberg, a radical, dissonant and powerful voice appeared in Vienna.

In Vienna, during the early 1900s, it was the responsibility of artists to display that not all the things underneath the city’s gilded, gold, the magnificent facade were beautiful. For a lot of artists, their target was the values of the bourgeoisie; however, for composer Arnold Schoenberg, a radical, revolutionary pattern was a more personal necessity.

Schoenberg was brought up in the Jewish society of Pressburg, what is now known as Bratislava, Slovakia, and was majorly self-taught on the piano. During the year1901, he relocated to Berlin and in the next year, he moved to Vienna. During the year 1904, he’d gathered a group of followers that comprised of the composers Anton Webern and Alban Berg.

Schoenberg was made the leader of a musical movement that accepted atonality, using the dissonance of works such as Salome and pushing it moving it further away from traditional tonality and melody. Still, his first work isn’t atonal. Transfigured Night shimmers in D-major that was done in the 1999’s, and his super-sized cantata Gurre-Lieder can be safely labeled as Wagnerian. In these works, there are just tips of the dissonance in store.

That change into dissonance and atonality matched with an issue in Schoenberg’s personal life. On the 4th of November 1908, a painter known as Richard Gerstl committed suicide after having a relationship with Mathilde, Schoenberg’s wife. Schoenberg had been a profound lover of Strauss, so, as at then, he’d been including some dissonance to work that still remained in tonality, especially his Second Quartet.

It sees the composer at a crossroads, where unpleasant dissonances like tritones thrive and the actual concepts of chords look to be collapsing before us. These musical transformations, together with the crisis in his personal life, brought Schoenberg into a creative era of early atonal works, ending in a 31st of March, 1913 program at the Musikverein alongside Webern and Berg.

In all honesty, already, his protégés were going farther out into the sonic desert than their mentor. In the song of Berg’s titled “Über die Grenzen des All,” a specifically annoying dissonant chord that has twelve various pitches made the audience to flare up into an outrageous mixture of catcalls, laughter, and a clash between the concert organizer as well as a member of the audience that led to a punch being thrown – and leading to lawsuit.

A composer that was in the audience referred to “the sound of the scuffle” as the most harmonious aspect of the musical program, and the press wrote wild with full-page articles about the incidence. Although, regardless of the reaction, Schoenberg had no aim of going backward.

Chapter 4 – With The Firebird and The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky rose to stardom.

Although the press may have been making jest of atonality, a “cult of Schoenberg” was rising among new Austro-German composers. While, in Paris, a related ardent following was building around a composer of a diverse variety.

Igor Stravinsky, the Russian-born man was brought us in a noble family of Polish and Russian lineage. His childhood comprised summer trips to Ustyluh, which is on the Polish-Ukrainian border, and it’s possible that Stravinsky was influenced at an early age by regional folk music – not different the type of rhythmic, dance-oriented music that similarly influenced composers like Frenchman Maurice Ravel, Hungarian Béla Bartók, and Leoš Janáček, from what would turn into the Czech Republic.

During the beginning of the twentieth century, mobile sound recording devices, as well as listening devices such as the gramophone, brought the music of both rural and remote areas to the ears of composers found in the city. The sounds, as well as the rhythms from hugely various communities across the globe, were starting to blend.

During the year1910, Stravinsky turned into something of an overnight feeling when his work The Firebird, which fused Russian folk traditions with French influences, was done in Paris. Especially, a part of the piece called the “Infernal Dance,” with its jaunty, rhythmically difficult utilization of bassoons, horns, and tuba brought a lot of surprises and started Stravinsky’s fame as a forward-thinking composer.

From that point, Stravinsky’s utilization of difficult rhythmic patterns grew braver and his sound easily explored the use of dissonance. But, in the year 1913, he immediately got to the positions of the most powerful composers with his work for the ballet The Rite of Spring, which was choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky and staged by the Ballets Russes in Paris.

Before the song debut, there were already gossips that the music, and the choreography, was going to push the boundaries of the avant-garde, and they actually did. during the second movement, the mixture of dissonant, jarring rhythms clashing notes, and wild dancing made specific members of the listener scream with dissatisfaction. A few fierce quarrels between protestors and Stravinsky’s ardent followers even arose.

This could be considered as a related “scandal” to the Schoenberg tragedy in Vienna; however, the only dissimilarity was that kind of rambunctious listeners were not rare in Paris. As a matter of fact, this act was bound to occur for a minimum of one or two times a year. Soon enough, The Rite of Spring was getting standing ovations, while Schoenberg’s atonal works kept on to defy all except most adventurous audiences.

Chapter 5 – Europe yearned for a new post-World War I sound, which arose in Paris, together with a jazz influence.

Immediately after the premiere of The Rite of Spring, Europe was put into the catastrophic brutality of World War I. English, Russian, French, and Austro-German composers similar were engrossed in either patriotism or their awareness of the ruin being brought about by the war.

Before World War I, the general public still had a feeling that the battleground could be a noble spot where pride, as well as glory, could be accomplished. However, this transformed for life during the twentieth century, as the war turned into a far more impersonal and disastrous issue and the dead bodies increased to unprecedented levels.

The war extremely transformed the growth of classical music. As huge areas of Europe were made into bloody battlegrounds, it led to a reckoning. During the year 1918, when the war came to an end, both composers, as well as listeners, were zealous for a new sound that had no connections to the past and didn’t have any connections that may have been tarnished by the war.

A group of composers called the Les Six arose in Paris. It encompassed Germaine Tailleferre, Georges Auric, Darius Milhaud, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, and, Francis Poulenc. They were extremely influenced by the ancient avant-garde stylings of Eric Satie and the new hostile music of Stravinsky.

New kind of music was arising, one that viewed the song of Wagner the exact manner Nietzsche had, as the “lie of the great style.” The pomposity and grandiosity that had been embraced by previous generations were ignored by the new post-war classical music.

American jazz was a different kind of new music that came in Europe during the war, and its rhythms, as well as textures, immediately started to be merged into contemporary compositions. Similarly, components of Bach, as well as other classical influences, started to find their path into the work of American jazz artists such as Duke Ellington.

In the midst of the transforming musical trends in Paris, there was a move towards formalism as well. More than only wishing to show feelings, or even anything related, formalists were concerned in the pure, intellectual act of making music. During that period, people such as Stravinsky proposed that music, as well as dance, should show nothing and that pure form and structure in music should take priority over an emotional association with listeners. This type of formalism would have a long-term influence, as we’ll get to realize in the following chapters.

Chapter 6 – Where classical music has European connotations in the US, a lot of composers played jazz or composed for Broadway.

Whereas, classical music has usually been at something of a weakness in the United States. The concept that classical music is a thing of European has proliferated there for long; also, since the time the nation escaped the British rule, the regular American listener has had a fondness for homegrown music.

During the start of the twentieth century, blues music, ragtime as well jazz definitely suit this bill, both in spirit and practically. However, that doesn’t signify that no American composers were making powerful work, in spite of the weakness of working in a European-dominated career.

During the turn of the century, the son of a bandleader known as Charles Ives was leading among the American composers. In spite of early good comments for a cantata done in 1902 tagged The Celestial Country, although, Ives still had a permanent work selling insurance. His contribution would proceed to contend with Schoenberg in its dissonance.

Permitted, there were as well a lot of European-born composers doing their work in America, such as Antonín Dvořák, that was given birth to in Czechoslovakia and relocated to the US during the year 1892. He got mesmerized with African-American spiritual music, morally praising African-American spiritual music as the future of American music.

Some American composers, such as Carl Van Vechten, change to performing in a more common musical style: jazz. As a matter of fact, the jazz music of America was being composed and done by a lot of artists with classical practice, comprising of the pianist called Fletcher Henderson. Other composers, such as George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein, pursued their talents to Broadway, where they obscured the line between musical theater and opera with works such as Show Boat and West Side Story, respectively.

Both Gershwin and the jazz pianist, as well as the bandleader Duke Ellington, were part of the first to mix jazz and classical music well. Even the famous Rachmaninoff, the Russian composer showered praise on Gershwin’s composition Rhapsody in Blue that was done in the year 1924. Also, in the year1934, Gershwin took the complexity of Mozart to the Black American experience in his opera Porgy and Bess.

Ellington was uncertain whether or not Porgy and Bess were actually “a negro opera,” as the press was labeling it because it was composed by a man that was born in Brooklyn to a Jewish family. For his part, Ellington was usually questioned if classically-trained jazz musicians were lessening their skills by playing jazz, and he used a lot of his profession joining the two kinds and demonstrating that jazz could be just as complicated. During a performance at Carnegie Hall in the year1943, Ellington presented Black, Brown and Beige, a piece that could correctly be labeled as a 45-minute “swing symphony.”

Chapter 7 – During the pre-World War II in Berlin, the politics of musical styles showed the deep separations in the community.

During the years after World War I, the ever-influential German music scene saw itself in a rare situation. During the year 1918, amidst the German Revolution, Kaiser Wilhelm II resigned from the throne and ran away from the country, heralding Germany into a thing similar to democracy in a period now referred to as the Weimar Republic. However, actually, what came after 1918 resignation was the political chaos that didn’t completely succeed to stabilize in the following decades.

Beginning in the year 1924, the chancellor and Gustav Stresemann, the succeeding foreign minister appeared to be the sole official who could have the extremist voices on the right and from tipping the country one way or the other way. Sadly, he died in the yeat 1929. The music of the time looks to copy this aggressive political condition.

You can consider it as the “politics of style,” and it would just become more contemptuous as the years proceeded. On one side, there were composers who wished to make “music of use,” compositions that might talk to the humanity of the regular individual on the street –a thing they might accept and feel stimulated by. On the other side, there were composers who were more concerned with formalism and producing music that pushed limits and developed the form, even if that entailed taking the music more into atonal dissonance.

The “music of use” mass was maybe best signified by a composer called Kurt Weill who, together with writer Bertolt Brecht, produced The Threepenny Opera in the year1928. Their music won over listeners in Berlin just like Gershwin’s music did with listeners in the US. Similar to Gershwin – and jazz musicians – Weill offered performers the opportunity to improvise and have their own imprint on the music.

Weill didn’t want music to be a thing for the cherished few. He wished for music to be clearer, simpler and more apparent. This wasn’t a thing that was accepted by the Schoenberg school of German composers. Rather, they were moving towards the twelve-tone kind of composing. Maybe as a usual growth of atonal and formalist music, twelve-tone basically changed composing into a difficult procedure; in the composition, a composer makes use of all the given scale’s 12 notes, or tones, before they can repeat any of them.

If this seems like extreme formalism, it actually is. Also, it showed extraordinarily durable, turning into the main influence on classical music between the 1930s to the end of the century.

Chapter 8 – Music in Stalinist Russia was influenced by politics as well and an America concern about Communism.

A lot of composers were stifled by the limits and machinations of the Soviet Russian government, especially during the 1930s and 40s, when Stalin’s influences were at their climax. Fascinatingly enough, just like Hitler, Stalin was a lover of music.

Definitely, both Hitler, as well as Stalin, fully knew the great musical legacies of their countries, and both of them wanted to make use of music to promote their interest. To Stalin, this entailed making music that doesn’t just confirm that the USSR was a place to topnotch composers; however, it was consistent with the values of Soviet Communism as well.

As composers from Russia such as Dmitri Shostakovich, Gavriil Popov, and Sergei Prokofiev found out, the values of Communism eventually turned out in direct contradiction to formalism. The leaders in the Communist Party made it obvious that the works of formalists would be prohibited and that Soviet music has to be the music of the people’s, clear and available instead of extremely difficult or atonal. Art must not be self-serving or indulgent, which is something leaders of Party could assume it to be if a composer were to try with a thing similar to twelve-tone composition.

As a matter of fact, in a conference that was held for three days in the year 1943, Andrei Zhdanov, the right-hand man of Stalin’s declared that 42 prior musical works were being prohibited officially, as well as the three symphonies by Shostakovich, Popov’s First Symphony, and two sonatas by Prokofiev.

It was a mystery since to be regarded as part of the best in their profession, modern composers needed to write music that pushed the form forward; that’s what a lot of experts thought formalist trends were causing. Therefore, it’s maybe all the more remarkable that Shostakovich and Prokofiev could make exciting as well as challenging music within the restrictions created in Stalinist Russia.

Sometimes, Stalin’s favorite was Shostakovich. But, during the mid-1930s, the composer was under scary examination after a 1936 show of his new opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. Stalin attended the show and left without giving any remark, obviously sad with how the composer’s made use of dissonance and jarring rhythms.

But, his Fifth Symphony was very well-received. It premiered in the year 1937 and succeeded to be emotionally difficult while at the same time winning over the censors. There is a clear journey from disaster to triumph in the song.

Also, in World War II, Shostakovich wrote his Seventh Symphony. The title was Leningrad, and it premiered in the city in its disastrous two-year attack by Nazi Germany. The show was concurrently broadcast over loudspeakers, strengthening the Red Army’s spirits while discouraging the attackers. Shostakovich kept on having a troubled relationship with Stalin; however, different from other composers, he succeeded to maintain an exceptional career under severe conditions.

Chapter 9 – In FDR’s America, composers talked about the type of music that has to be made as an influx of European refugees came in.

During the time that the US became part of Allied Forces in World War II, there were politics of style debates initiated as well. What was the position of music in the community? Should a composer be only keen on promoting their work, or should they be creating music “to be of use,” like Benjamin Britten an English composer mentioned one time of his ambitions?

In the US, During the 1930s, this period was as well an intense period of attempting to bounce back from the Great Depression, while the rising fame of radio permitted for new ways of mass communication. President Franklin Roosevelt declared his huge New Deal project, which at first comprised of a benevolent budget for assisting the arts.

An aspect of the Federal Arts Project was music-based and made to assist composers as they made their following influential works. At first, the music program got $7 million and it was distributed to around 16,000 musicians as well as 125 orchestras.

However, as soon as federal taxpayer money goes to the arts, where that money ends up and who gets it is certain to be inspected by politicians trying to score points and be in headlines. That’s exactly what occurred between the years1938-39, as Republicans trying to chip away at FDR’s authority confronted the federal program as a propaganda machine, bringing about its destruction.

Aaron Copland was one composer who truly experienced the impacts of political inspection. Different from other composers, Copland held populist motives all through his profession, although he got dissonant now and then. Usually, Copland is well-known for pastoral works that invoke the big area of America. His score for the ballet Billy the Kid starts with a piece titled “The Open Prairie” and it succeeds to invoke that type of landscape well.

Copland valued open communication in music and also, he thought that it could have a social message as well. During the time of the Depression in America, there were powerful communist and socialist movements, even though Copland was interested in their messages he never became an official member. However, in the year 1949, he went for an occasion known as the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace, which gave him the chance to come across Dmitri Shostakovich and voice out against the manner Cold War fear could extremely impact art.

Afterward, the FBI opened up a file on Copland, and it was clear that his work was seen in a different way from then on –maybe also due to the reason that Copland was homosexual, and hence regarded as a possible KGB blackmail target.

Chapter 10 – Post-war Germany witnessed the establishment of the Darmstadt School, whereas the avant-garde became more hostile.

The post-World War II music scene not just stayed alienating; however, it became even more so as well. Similar to how it had occurred following the First World War, there was a reckoning after the Second –specific music took on new connotations taking into consideration the war’s atrocities. The type of grandiose music that was preferred by dictators such as Hitler, who liked the work of Wagner, was cast separately for new musical crazes that didn’t have any historical baggage.

A new avant-garde appeared during the Cold War period in Germany and France and it was more aggressive and hostile than before.

Although the officials in post-war Germany were thinking about the kind of song to play on the radio, the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music was produced in the year 1946. This turned out to be the home base for an extremely powerful group of composers called the Darmstadt School. Initially, twelve-tone appeared as the stimulating kind of decision for the young composers; however, soon enough, the forward-thinking group considered this passé.

During the 1950s and 60s, new developments in electronic devices signified that electronic music and manipulation were immediately accepted for their thrilling new possibilities. Karlheinz Stockhausen was one of the leading voices from the Darmstadt school was, who immediately moved from one style to the other. All the names that Stockhausen made use of to label his formally ambitious compositions were point music, serial music, and statistical music.

Similarly, in Paris, a new group of composers was drifting toward Pierre Boulez, who was maybe more hostile than any other person in calling formalist, atonal music “the only means forward”; every other music was “useless.” Specifically, Boulez was an advocate of a new method known as total serialism, which took a lot of parts of twelve-tone serialism and plotted all of them like coordinates on a grid, from scales of rhythm and pitch to note length and dynamic levels. This could bring about the note E Flat usually being played for 30 seconds and always at the exact same dynamic within one piece.

A lot of composers rallied around people such as Boulez and Stockhausen and create limits about which methods and forms were the appropriate way forward and which ones weren’t. Whereas, in the States, a different type of avant-garde scene was growing.

Chapter 11 – From the American West Coast, Minimalism originated and took control of the bohemian art scene in New York.

During the 1930s, a lot of European composers ran to the US and some of the composers, for instance, Schoenberg, got teaching jobs at universities. Stravinsky, Schoenberg, as well as other composers discovered the warm and sunny climate of California to be a pleasant new place to refer to as their home.

A lot of relocated composers got a steady job writing songs for Hollywood. Also, maybe motivated by the low desert landscape and the long as well as open roads, other composers were forming a brand new type of avant-garde music that would be referred to as minimalism.

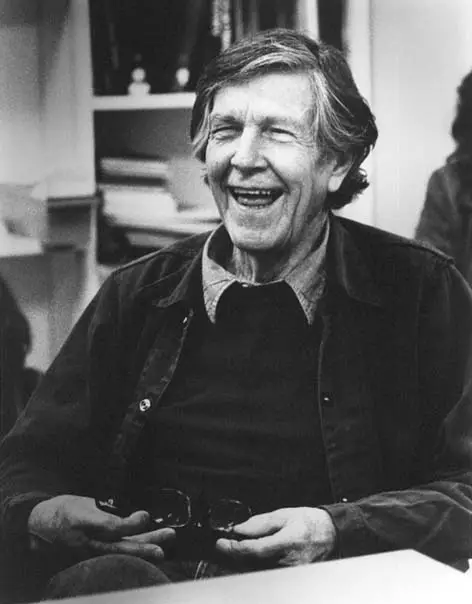

During the 1930s and 40s, Schoenberg was a teacher at the University of Southern Californi and Schoenberg was a direct influence on a lot of rising composers, as well as Lou Harrison and John Cage. Schoenberg loved telling his student that, “Use just the essentials.” Harrison may be used this advice in manners Schoenberg didn’t essentially mean to, by making scanty musical landscapes comprising of droning chords and hypnotic patterns.

Cage moved between the West and East Coasts before eventually living in New York, living among the city’s avant-garde artists and becoming friends with other musicians such as Morton Feldman, a fellow minimalist composer. Also, Cage got valuable knowledge from journeys abroad, going to Paris and Darmstadt, where electronics and tape manipulation were turning into common components for technology-savvy composers.

In New York, the bohemian art scene there was a really open and collaborative surrounding, where writers, musicians, choreographers, and painters, were floating in and out of one other home and sharing their concepts. Mark Rothko and Robert Rauschenberg were only a couple of the contemporary artists who got motivation from contemporary classical music and similarly influenced composers.

Rothko’s large arts with bold areas of softened colors are a great visual depiction of the droning, soothing sounds of the minimalist song. It is maybe appropriate that Feldman would form a key work after the artist’s passing, titled Rothko Chapel.

During the 1950s and 60s in New York, there was an uptown-downtown separation. On Broadway, the European-style classical music was still an influence; however, a very new experimental view was developing downtown, and at the core was Cage.

As we’ll realize in the following chapter, there were some vital dissimilarities that made Cage different from the European avant-garde.

Chapter 12 – The classical composition was deconstructed by John Cage as minimalism gave a way to progress.

During the1960s, methods such as twelve-tone and complete serialism had apparently taken formalism as far as it could get. Music had become as atonal, discordant and polyrhythmic as it likely could get. Hence, this way, minimalism can be regarded as a natural reaction, a resetting of classical music composition that brought a feeling of tonality, space, and a more repetitive rhythm back.

Maybe the most daring minimalist show as Cage’s 4’33”, also referred to as his “silent” piece, whereby the performers doing it basically sit at their instruments and didn’t play any note for about 4 minutes and 33 seconds. The “music” is the sound of the setting the show is happening.

In various means, Cage was similar to the Marcel Duchamp of music. Similar to how Duchamp playfully deconstructed contemporary art, Cage deconstructed musical composition to show its innermost machinations. This is what actually makes Cage different from the European avant-garde and maybe the cause that people such as Boulez showed hatred for his work.

The twelve-tone and the serialism that Boulez supported had a vital component of randomness to them. Decisions the composer took at a time would compulsorily decide what occurred after. Cage made that randomness easily clear. He got instructions from the Chinese I Ching, an old prophecy text, and he would toss dice to determine the tones, tempos, notes, and interval of sounds would come after in his compositions. The act of creating music was not a mystery anymore that just the top composer was able to do.

Cage’s shows usually took the shape of “happenings” that were more similar to performance art; also, as the counterculture movement of the 1960s happened, multimedia occasions were popping up. Minimalist composers La Monte Young planned the Theatre of Eternal Music on the West Coast, which included shows by Terry Riley, who usually made use of a mixture of tape loops and drones to hypnotic result, and John Cale, the cellist who would proceed to become part of The Velvet Underground an avant-garde rock band.

During the 1960s and 70s, composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich were as well creating monumental works. Glass added features of the work of Indian musicians such as Ravi Shankar into his compositions, whereas Reich utilized repetition to excellent heights. These two composers really discovered a means to make modern classical music not just adventurous; however, common among listeners as well.

Chapter 13 – Classical music’s influence of the Twentieth-century can still be found in the current eclectic pop music.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, musical influences all across the globe were joining together and the progressive methods of determined composers were having their way into common music.

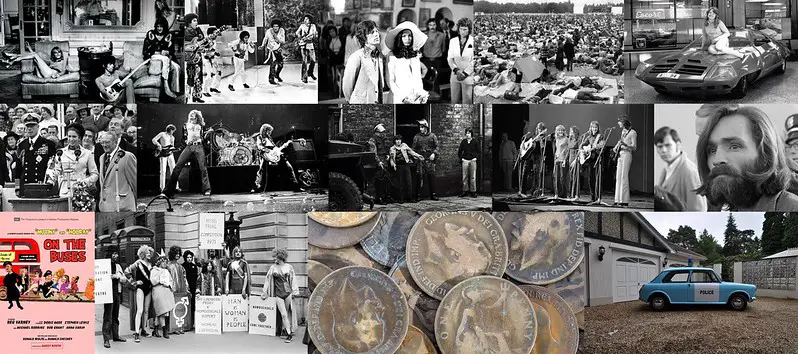

In the song “Baba O’Riley” that was sung by The Who, they offered small respect to modern classical music which gets its title from Terry Riley, the psychedelic minimalist. Also, there’s an image of the Darmstadt School’s Karlheinz Stockhausen in the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album, whose compositions as well as the utilization of tape manipulations would inform the band’s more experimental songs. Before Stockhausen died in the year, Stockhausen himself used 26 years working on a song titled Licht, which is included seven song cycles, one for every day of the week; he finished it in the year 2003.

Advances in electronic music, as well as programmable synthesizers, stayed as a concentration for a lot of composers in both the US as well as Europe. However, after a specific point, new composers were developing with rock and roll, jazz, as well as pop music instead of classical.

A key illustration of contemporary classical music with a pop sensibility is the New York collective Bang on a Can’s work. Maybe, better called Brian Eno, who began with the rock group Roxy Music before going on a journey as a producer of ambient music that owes a lot to the minimalists who came before him.

Also, additionally to the Velvet Underground, contemporary rock bands such as Sonic Youth have appeared steeped in the experimental song scene of New York that Cage was really an influential part of. Artists such as Sufjan Stevens, Joanna Newsom as well as Björk, Radiohead, have all made works that are extremely informed by the classical music of the twentieth century.

However, although your regular three-minute pop song tops at having an instant impact on the listener, it’s hardly competent of exploring what Debussy referred to as the “imaginary country” one time. In order to completely explore the difficulty of the human experience, a composer has to possess the openness of the classical format – a big, extensive format, which lets the composer go anywhere their inspiration may take them to, from total silence to total noise.

The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century by Alex Ross Book Review

The classical music of the Twentieth-century is a shadow of the eras in which it happened. Disastrous wars incited composers to escape from the historical burden that arose with prior works and progress with new, progressively dissonant and formalist compositions.

Also, just like they were intense political separations across Europe as well as the US, there were musical separations as well and politics of style, which became more aggressive during the second term of the century at the top of the avant-garde movement. However, as soon as formalism, as well as atonality, had been pushed as far as they could, minimalism and electronic compositions arose to provide composers a new means forward.