Warren Buffett is possibly the twentieth and twenty-first century’s most known investor – maybe even of all time. Identified as the “Oracle of Omaha” or the “Sage of Omaha,” his view on business and politics can also be seen in the newspapers for many years. But few know what he really does and much less on how Buffett came to hold the place in which he is today.

In this review, we dig into Warren Buffett’s life and track him from his early childhood to his first entrepreneurial ventures to his new status as a modern American entrepreneurial sage. His story gives an interesting and informative insight into life’s business.

Chapter 1 – Warren Buffett, as a youngster, found warmth and pleasure in numbers and statistics.

Warren Buffett was born on August 20, 1930, in Omaha, Nebraska – just ten months after Black Tuesday, the stock market crash that brought the nation down into the Great Depression.

His father, Howard, was a well-loved stockbroker who during this grim time managed to sell respectable shares and bonds. As a result, the Buffetts were able to come back from the depression and survive happily throughout the 1930s dissimilar to many other households.

That didn’t mean that things were convenient for the young Warren though.

His mother, Leila, was an autocratic parent, quick to launch into a fury, an unhealthy habit that led her to ridicule and accuse her children in vain.

Stuck with this abrasive and unstable parent at home, Warren was ready to find a way out. Most often, the object of their mother’s anger was his older sister Doris, but Warren often tried means to escape the fury of his mother, and discovered it in numbers, odds and percentages.

He liked school mostly because it took him away from home and taught him more about math.

After getting out his first-grade lessons, Warren and his friend Russ would hang in front of Russ’s porch and write down the passing cars’ license plates. Their families thought this was because they could quantify the frequencies of each letter and number appearing on the plates, but in fact, the two of them covertly assumed that their notes could be helpful for the law enforcement to find bank thieves because the street was the only potential getaway route from the local bank.

Occasionally, spending time at his dad’s office on the weekends, where he gladly wrote the number of stock rates on the large chalkboard of the office, he managed to get away from home.

Other family members acknowledged and supported the young Warren’s interest in numbers, odds, and statistics. At eight years old Warren received a book on baseball statistics from his grandfather, a present that fascinated Warren. He spent hours on end memorizing each sheet.

His favorite aunt Alice sent him another gift: a book about the intricate card game bridge that started a lifelong fascination.

Warren could sit comfortably in his room with these fantastic books, away from his unpredictable mother, and spend time in the company of more soothing and trustworthy companions: numbers.

Chapter 2 – At an exceptionally young age, Buffett started making money and investing.

Only one thing attracted Warren more than numbers and that thing was money.

At nine years old, Warren was earning money already by selling bags of gum and bottles of Coke in his neighborhood. After a year, he sold peanuts at the University of Omaha’s football games.

Warren’s curiosity in finance picked up in 1940 when he spotted a book named One Thousand Ways to Make $1,000 at the library. Instantly influenced by it, the ten-year-old Buffet confessed to a mate that he intended to be a millionaire by age 35.

He definitely proved to be a dedicated kid: he had already saved up $120 by the age of eleven, which in 1941 was a huge amount of money.

He used the funds to make his initial investment. He acquired six of the company Cities Service Preferred shares – three for himself and three for his sister Doris.

The odd jobs persisted in high school; he sold golf balls and purchased pinball machines which he rented out at hairdressers.

But when he began distributing newspapers, his earnings really skyrocketed.

His family had moved to Washington, DC in 1942 after his dad was elected as the Republican delegate for the second district of Nebraska to serve in congress.

It was here that Warren began distributing papers and selling subscriptions to three separate paths, one of which included three famous apartment buildings home to several senators in the United States.

Since Warren received a percentage of the subscription fees generated, he was a highly driven delivery boy and a disciplinary to make sure that his customers paid up.

Incredibly, at this point, he was making about $175 a month – better than any of his school’s instructors. His savings had risen to $1,000 not long after.

Warren filed his first tax return in 1944, at the young age of 14. He listed his watch and bicycle as deductions, paying a sum of $7.00.

Chapter 3 – Having studied business at college, Buffett discovered from his professors the secrets of success in the stock market.

Given Buffett’s all-consuming curiosity in money and numbers, it comes as no surprise that his friends chose him in the high school yearbook as a “Future Stockbroker.”

The fact that Buffett wanted to study accounting and business at the University of Nebraska was also expected by his family and friends.

It became evident when he moved out of his family home to a college campus that he was a pretty disorganized person. In reality, Buffett’s messiness irritated his first roommate so much that he wanted to move out after the first year of them staying together in the dorms.

But maybe his roommate was more annoyed by Buffett’s ability to memorize whole parts of textbooks easily, which he could then read back to his professors verbatim.

This allowed him to listen to music for longer periods of time and not tidy up after himself, much to the frustration of others who worked for hours in order to pass their classes.

Since Buffett considered college quite effortless, he was rather shocked when he got a letter of refusal after applying for a degree program at Harvard Business School.

But it has been a blessed setback. Buffett was admitted into Columbia University, where he studied under the author of the book Intelligent Investor, Benjamin Graham, and a man whose mentoring made a huge impact on Buffett.

Buffett cherished the book of Graham dearly therefore he forgot all about Harvard when he found out he was teaching at Columbia. He was also enthusiastic about another class that David Dodd, the author of Security Analysis, taught, yet another book that Buffett knew by heart.

These two teachers taught Buffett useful lessons and basic investing techniques.

For example, Buffett learned about the significance of researching a business from top to bottom to assess the intrinsic value – the amount of money it truly is worth. This value is then compared to its perceived value, which is how much the stock sells for on the market at the moment.

When the intrinsic value of a firm is much greater than its market valuation, it could be what Graham terms a “cigar butt” – an under-estimated enterprise worth investing in. The popularity of Graham was primarily focused on the assumption that there is a strong probability that the expected value will inevitably rise above the intrinsic value.

Chapter 4 – Buffett became his own boss by forming a unique partnership, after starting a family.

Buffett had been awkward with girls in college. His social anxiety was so serious that he even registered in a public speaking class, hoping that it would improve his confidence and help him feel less insecure.

There was especially one young and beautiful woman who Buffett had in mind while taking this class.

Her name was Susie Thompson, and even though her father liked Buffett in an instant, it took more patience before Susie warmed up to him and his awkward nature.

An anxious mess, Buffett first came across as vain and entitled, and too willing to please. But when Susie gave Buffett a shot, she knew his grandstanding was just a sign of his insecure shyness and finally fell in love with his charming weakness.

In 1952, the two of them got married, and Buffett stayed busy teaching lessons and working at the old brokerage firm of his dad.

Susie Alice Buffet, their first daughter together, was born in 1953. It was the same year Buffett got his dream job, working in Ben Graham’s investment company, Graham-Newman.

Buffett quickly became Graham-Newman ‘s superstar although he soon discovered he disliked becoming a stockbroker.

He couldn’t bear the possibility of taking up the wrong investment and wasting hard-earned money from others. So he immediately started to plan his own partnership.

After his second child, Howie Graham Buffett was born, Warren’s aspirations to become his own boss were made a reality. He founded Buffett Associates, Ltd in 1956.

The premise behind this partnership was that it would consist of friends and family only, and behind any commitment, there would be clear guidelines so that no one would be disappointed or have unreasonable expectations.

At the same time, his mentor and former employer, Ben Graham, gave Buffett’s credibility a lift. Graham chose to resign and shut his business down shortly after Buffet had quit his business. But as he resigned, he suggested Buffett as a trustworthy man for his customers to invest their money with.

Chapter 5 – The rigid principle in the initial partnership he stuck by turned out to be very rewarding.

Buffett started a series of eight partnerships in his first year as his own boss based on various groups of friends that offered him anywhere from $50,000 to $120,000 to invest.

Any time Buffett began a new partnership he made sure his principle was known by everyone.

He would tell his future investors how he just traded in undervalued securities and then reinvested any profits into the same securities. In a way, it was like rolling a snowball down a hill: slowly, what starts off as a small handful grows larger and larger.

He was not the type of investor who would cash out when a stock passed a certain amount – he was patient with the stocks – and he made sure his clients knew that.

Eventually, this patient consistency turned out to be worthy of. His partnerships surpassed the market rate by 4 percent at the end of 1956; it was 10 percent at the end of 1957, and 29 percent at the end of 1960. The snowball was now rolling.

Buffett was controlling over a million dollars by the early 1960s. The stock market was on an upward trend at this time; but, unlike many other investors, this move in the economy did not affect his way of doing business.

He was always looking for undervalued businesses and he purchased up as much stock as possible once he found something he desired.

Sometimes this included winning a seat on the board to make sure the management did nothing stupid with the funds of the investors.

Amazingly Buffett was also doing all of his own papers while handling millions of dollars. But he wanted to make matters less difficult in 1962 and merged all of his existing relationships into one entity: Buffett Partnership, Ltd.

Buffett’s reputation started spreading beyond Omaha to Wall Street during this time, where he was attracting attention as one of the few big stars who didn’t work in New York City.

Some famous financiers, though, remained cynical and expected that any day now, he would go bankrupt.

Chapter 6 – The partnership became large enough in the mid-1960s for Buffett to start purchasing entire companies.

One man who noticed Warren Buffett’s skills early on was Charlie Munger, a Californian lawyer, and part-time businessman. After a long lunch in 1959, the two like-minded people became friends quickly -a relationship that eventually led to beneficial business collaboration.

Munger’s insight opened Buffett’s eyes to greater possibilities and made him understand that when going past those “cigar butt” stocks, you can still play it safe.

Indeed, the Buffett partnership would take a big step forward shortly, mainly thanks to some stock that Buffett purchased at the right time.

When John F. Kennedy was murdered in 1963 few people paid attention to any other news. Yet Buffett was a very habitual person by then, and he kept looking into the paper’s back pages, where he stumbled across a report about a soybean controversy involving American Express.

A subsidiary of American Express had reported that some storage tanks held soybean oil but later it was discovered that they were loaded with seawater. American Express supplies have had a serious impact as a result. But Buffett wasn’t concerned about this; he knew the firm would make a comeback.

Then, when prices reached rock bottom in January 1964, he started steadily pouring capital into American Express: at first $3 million, and then $13 million, by 1966.

American Express did come back, of course, and it added unparalleled benefits to the partnership, enough for Buffett to consider buying whole firms.

Among the first buyouts was a company that would come to describe Buffett – Berkshire Hathaway, a small textile maker in Massachusetts.

Analysis by Buffett found that its intrinsic value was $22 million which meant it was expected to trade at $19.46 per share. Yet it only sold at $7.50 per share.

Buffett got a controlling stake in Berkshire Hathaway in 1965, thanks to some bargaining, by buying 49 percent of the firm at a little over $11 a share.

The same year, Warren and Susie made an extra $2.5 million, mainly due to the American Express acquisition, which meant Buffett’s target of becoming a millionaire by age 35 was more than achieved.

Chapter 7 – Bigger challenges emerged with bigger purchases, with some new rules to adopt.

Although Buffett is now closely identified with Berkshire Hathaway, it was so troublesome for the company that Buffett would end up regretting being associated with it.

But Buffett isn’t the sort of investor who wants to cut down on his expenses, a concept that goes long back even before Berkshire Hathaway got involved.

Buffett made a similar acquisition in 1958 of a Nebraskan-based firm named Dempster Mill Manufacturing, which produced windmill and water irrigation systems.

But things have gone wrong rapidly: he selected the wrong people to be in charge, the business went bankrupt and he wanted to liquidate the assets of the company. As a result, people were laid off and their hatred of Buffett was publicly voiced by the local neighborhood.

He was determined never to see this occur again, Buffett decided to make sure that Berkshire Hathaway had the right manager in charge and that the company was intact.

This posed many problems as cloth prices increased during the 1960s and 1970s and the infrastructure of the company was in urgent need of modernization. But Buffett never wasted funds, therefore he was highly reluctant to pump new cash into a business that didn’t carry any real potential to make a profit.

All of this implied Berkshire Hathaway as a clothing producer would continue to be a liability. Nevertheless, Buffett kept it going by trying to buy winning stocks under its name at any opportunity he had, finally providing Berkshire Hathaway one of the best stock holdings in the world.

Despite Berkshire Hathaway’s issues, Buffett’s been doing exceptionally well. His business partnership was so successful that he decided to shut his doors to new investors and tighten his regulations on investments.

In the late 1960s, even more, technology companies appeared which caused Buffett to come up with a new principle: he would never purchase stock in a business that sold a product or service that he did not completely comprehend.

Buffett preferred things “simple, secure, productive and enjoyable”, which led to another principle: no association with companies that had possible or confirmed “human issues” such as imminent layoffs, plant closures, or a history of managers arguing with labor unions.

Chapter 8 – As the partnership came to end, the Buffets continued to participate in more intimate, and independent, activities.

He remained a famously shabby dresser long after Buffett became a millionaire, a man completely unconcerned with his outer image. For Buffett, the specifics and personalities of the individuals who were responsible for his company were much more significant.

Stable companies have stable executives, therefore as Buffett made the investments, he made sure the right people were running them.

The people behind the scenes were one of the key reasons that Buffett wanted to buy the Baltimore department store Hochschild-Kohn as well as Associated Cotton Shops which run a series of retail stores.

Buffett used to sit down with the business management to get to know them well. He needed to make sure the people he could confide were excited.

Buffett had his sights on an insurance firm called Omaha National Indemnity for a while. But he wanted to buy right away when he met Jack Ringwalt, whom he quickly identified as a fantastic boss.

These were good decisions, and the company did better than ever before by the end of 1966, outperforming the industry by 36 percent.

Buffet saw the managers of these companies and his investment partners as family. Around the time the 1960s were coming to an end, Buffet started proposing to buy out his associates.

It was a way to slow down the partnership so he and Susie could be more focused on personal activities.

Susie kept hoping that her husband would retire, or at least devote more time to his children, who were growing up quickly without much attention from their father.

Susie was busy too: she sought a musical career and became involved in America’s urgent social problems of the 1960s, supporting civil rights and demonstrations against the war.

Even Warren, who had always been moving away from politics, could not help but get engaged. He became the treasurer for Democratic presidential nominee Eugene McCarthy for the Nebraskan office in 1967.

Warren’s step into politics had a great deal to do with his father’s death, he was a committed Republican. Buffett was eventually free to share his own political opinions after his father died, without thinking about offending him.

Chapter 9 – Buffett got into the newspaper industry in the 1970s.

Back when Buffett was in Washington, DC, distributing newspapers, he dreamed of having his own newspaper someday. And when he made an income of $16 million in 1969, he was actually in a position to fulfill the dream.

Buffett had acquired a majority stake in the Omaha Sun last year. This not only fulfilled one of Buffett’s dreams; it would finally lead to a coveted honor.

The Omaha Sun published an investigative report on Boys Town, formerly an abandoned boys shelter dating back to 1913, in 1972. By the time the article was published, this shelter had been a vast 1,300-acre property run by a priest called Father Edward Flanagan, with his own farm and stadium.

Curiously, however, it only held 665 boys – and 600 staff.

It looked as though something shady was happening, so Buffett supported an investigation by the Sun’s editorial board. And the hunch of Buffett’s lead to a major leak. In reality, Boys Town had stockpiled contributions, grants, and loans, raising about $18 million a year.

The story – “Boys Town: America’s Wealthiest City?” – ran on March 30, 1972, winning his paper the Pulitzer Prize for outstanding regional journalism. The story quickly went national and contributed to reform of how non-profit organizations managed.

Buffett set his eyes on a national newspaper after this success: The famous Washington Post.

Buffett bought over 5 percent of the Washington Post by the summer of 1973 and had formed an incredibly intimate friendship with its editor, Kay Graham.

He joined the board of the newspaper the next year and began attending the extravagant dinner parties of Graham. He spent several nights unsuccessfully trying to mingle with celebrity guests like the actor Paul Newman and hoping not to embarrass himself before esteemed senators, ambassadors, and dignitaries from all over the world.

Chapter 10 – Buffett encountered a reasonable amount of early obstacles including a difficult inquiry by the SEC.

When you’re an activist as involved as Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, you’re bound to pick up a few challenging businesses.

When Munger discovered Blue Chip Stamps, it was 1968, and while they were at grocery stores and gas stations, it was popular for housewives to buy trading stamps-which acted just like vouchers.

But in the 1970s, with the emergence of the women’s liberation movement, exchanging stamps became past – nostalgic symbols of a less tolerant age.

Like Berkshire Hathaway, Blue Chip was on borrowed time now; it was alive only because Buffett and Munger bought high-performance stocks under the company’s name.

So, to support Blue Chip, Munger purchased 8 percent of Wesco, an undervalued savings and loan firm.

Buffett liked Wesco too, but Santa Barbara Financial Company did like it too. SBFC did indeed intend to merge with Wesco.

But Buffett saw SBFC as an overvalued firm, which for Wesco would just be bad news. But he went to California to speak with the remaining member of Wesco’s founding family, Betty Caper Peters, and persuaded her to call off the merger. She did, but the move triggered a decline in Wesco’s stock from $18 to $11 per share.

Buffett and Munger felt terrible about that so they bid $17 per share to purchase their majority stake.

But it did not stop there: Santa Barbara Financial lodged a claim with the Security Exchange Committee (SEC) alleging that Wesco was deliberately overpaid by Buffett and Munger to spoil the intended merger.

1974 has been a stressful year. The SEC opened an investigation into the complex web of more than 30 companies run by Buffett and Munger. This included five parent companies, like Berkshire Hathaway and Blue Chip, each owning five or more other firms, which in turn owned other firms and so on.

They had nothing to hide, but the complex structure made the SEC extremely suspicious.

Buffett was profoundly worried. He knew that even being named in a finding of wrongdoing might destroy credibility forever.

Luckily, in the end, only one warning was given by the SEC for a disclosure breach in the history of Blue Chip-and no people were named.

Chapter 11 – Buffett also went through troubling times with his marriage and a legal fight involving two newspapers.

Susie was originally disturbed by the extremely close relationship between Warren Buffett and the Washington Post editor, Kay Graham. But, she finally started an affair with her tennis coach and wrote a private letter to Kay, informing her she was free to have her own affair with Buffett.

But in 1977, with the kids out of the home, Susie felt it was time for a dramatic change, and plans were made to relocate to San Francisco.

Buffett never grew up, in several aspects. Although he was close to fifty he was always a dirty guy who loved ice cream and cheeseburgers. He also stayed much more committed to his business than to his family.

Susie really loved him through all this and needed to make sure he was taken care of.

Therefore she hired Astrid, a young woman who Susie met from a bar, to cook for and care for Buffett when she departed.

Susie’s leaving saddened Buffett, but after several weepy phone calls, he eventually realized she wanted a life of her own.

Astrid finally moved in with Buffett, which shocked both Susie and Kay also Howie and Susie, Jr.

Then a messy legal dispute started in the midst of all this and would take years for Buffett to settle.

Buffett and Munger had added a new newspaper to their portfolio in the late 1970s: the Buffalo Evening News. Part of their strategy was to attach to the paper a weekend edition which they would launch by selling the first five issues free of charge, followed by a discount.

But their rival in the field, Courier-Express of Buffalo, filed a lawsuit, alleging this deal was an unfair practice.

Through ruling in favor of Courier-Express, the judge shocked Buffett. In his verdict, the judge said distributing free newspapers was unconstitutional and if the people decided to subscribe to the weekend edition they would have to renew their subscription every week.

Normally, Buffett appealed this unfair ruling, and eventually prevailed in 1981, but by that time the paper had lost millions of dollars.

Chapter 12 – Being a true companion brought Buffet to Salomon Brothers, where he was presented with one of his most challenging tests.

Another business with which Buffett is closely connected now is GEICO, an automobile insurance firm that Buffett first encountered back in college. It was also one of the first stocks he introduced to clients at his father’s old firm during his brief tenure, but it wasn’t until the 1970s, when the business was in turmoil, that he got closely engaged.

In 1976, Buffett joined GEICO’s board by modernizing its management to get it out of going bankrupt.

A managing director named John Gutfreund, who worked at the Salomon Brothers trading house in Wall Street, helped Buffett collect funds to get GEICO back on the right track.

Buffett was thankful for Gutfreund’s support and wanted to return the kindness, while Salomon Brothers faced some of their own problems.

Hostile takeovers became a common way of doing things on Wall Street in the early 1980s; bad loans were used to make traders wealthy, and everyone racked up the debt by doing loan-based transactions.

Buffett, who always paid in dollars, despised these activities and neither did he like the traders or analysts who engage in them. But when Gutfreund applied for his assistance in 1986, Buffett decided to join the Salomon Brothers board.

Buffett has such a reputation for being synonymous with reputable and successful businesses that it was a strong indication to many that the business was in safe hands and not prone to takeover.

Yet Buffett never expected the danger ahead.

A worker named Paul Mozer was swept up in a major controversy in 1991. He had violated several federal rules by secretly participating in government contracts.

To make it worse, before the word broke, management was made aware of that but had not taken appropriate action.

Buffett was made temporary CEO during the aftermath, and he put together new management and changes. He used his connections to argue his case and effectively stopped the Treasury from banning Salomon Brothers from future auctions.

Chapter 13 – Buffett’s growth, through an eye-opening relationship with Bill Gates, has persisted without technological improvements.

In the 1990s, the prestige of Warren Buffett took a negative turn. Buffett remained completely uninterested in NASDAQ, as technological stocks became all the rage. People have begun to say he was behind the times, an obsolete old guy.

Strikingly, Buffett never bothered himself with these views, even without the stocks of electronics he seems to be doing just great.

Probably he was more than great: his net worth soared from $89 million to $3.8 billion and increased between 1978 and 1991.

And after becoming Berkshire Hathaway’s CEO in 1986, the shares of that business began to skyrocket, trading at $8,000 a share in 1991 and then exceeding $10,000.

His experience is proof that while steering clear of the NASDAQ you will remain important and successful. Buffett was one of the few people who understood that the only thing tech companies did consistently were long-term unhappiness for investors.

He did make a tiny investment in a single business, however.

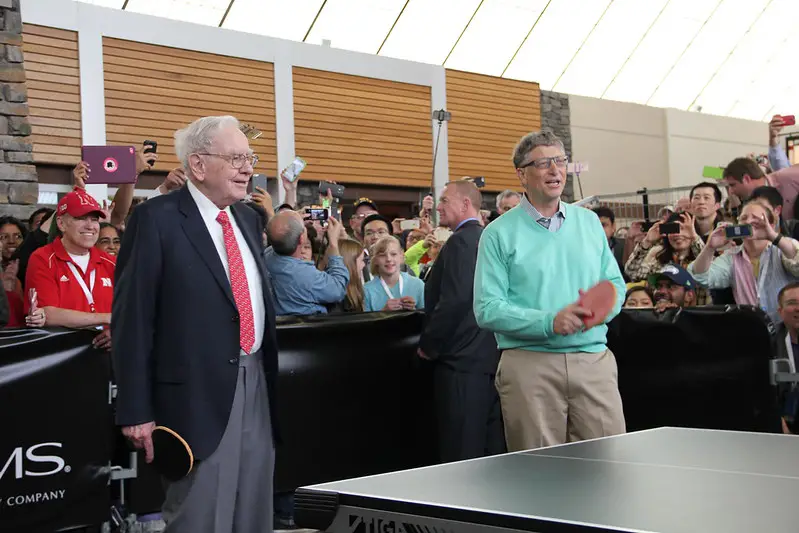

Warren Buffett and Bill Gates decided to meet at a July Fourth party in 1991, even though they all went on to believe they might not have much to talk about.

But the encounter led to a discussion that lasted over the weekend, and they continued to stay close friends.

Afterward, Gates started attending the annual shareholder meetings of Buffett, which soon became so popular that resellers could sell a $250 fare, and ultimately Buffett purchased 100 Microsoft shares.

Buffett and Gates, along with Charlie Munger and Kay Graham, also started meeting frequently for bridge games.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, these two have been competitors for the title of the world’s richest male. But it was their relationship that opened the eyes of Buffett to his rightful place in the wider universe.

Buffett learned how fortunate he was to be born in Omaha, after going on a trip to China with Gates.

He unquestionably realized that he had opportunities that many others in the world did not have, a recognition that only increased his positive and respectful approach to life.

Chapter 14 – Buffett suffered personal setbacks in the 2000s, which had him reconsider what was important.

Buffett’s warnings of online firms being a failure for consumers had already proven true in the early 2000s, and he was already rebranded as a visionary by newspapers that rendered him obsolete in 1994.

Still, in 2001, when his best friend and partner Kay Graham passed away, this reversal was not much consolation.

Their partnership of thirty years had been incredibly close and he was shattered for weeks after her passing.

Then things just got tougher two months later, on September 11, 2001.

Buffett took what he knew from all of these incidents – that we are living in challenging times – and started investing in businesses that gave a certain level of confidence. This is what attracted Buffett to businesses like Fruit of the Loom and to firms that produced farm machinery and clothing for kids.

But another re-evaluation time was very close.

Susie had been diagnosed with stage 3 oral cancer in 2003.

And though they did not live together anymore, Susie and Buffett stayed together. Even though he was sometimes moved to tears, he understood the value of taking this time to care for Susie.

Susie died in 2004. Buffett felt grief-stricken, and was in bed for many days, refusing to speak to anybody. But he had been in great contact with his own emotions when he eventually appeared he had an urge to get closer to his children.

He claimed that he had now found the secret of life: “… to be loved by as many people as possible among those you want to love you.”

He had understood what he needed to do with all his resources too. He gave the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation 85 percent of Berkshire Hathaway, which at the time was worth $36 billion, and he split another $6 million between Susie’s benevolent foundation and the other foundations established for his kids.

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life by Alice Schroeder Book Review

Warren Buffett had a one-track mind for the majority of his life – rolling the snowball. This has meant saving and reinvesting profits continuously. His reasonably easy and comprehensive investing strategy for choosing stocks has little to do with industry patterns or technologies.

Use Buffett’s “20 Punches” approach to investing.

Think about getting a wallet that just offers you 20 ways to spend in your lifetime. Any time you make an investment, someone is puncturing a hole in your card and you are losing a chance at a potential investment. If you follow this theory, the decisions you make would be much more cautious.