Amanda Palmer, the American musician recorded a video in 2012 and she posted it on Kickstarter. Although, this wasn’t your usual plea for contributions.

While Palmer was standing by the corner of a street in Melbourne, she held up various signs. These signs narrated her history– how she’d abandoned her former label and wished to start out on her own and really reward her collaborators for their job. It was an amazing success. For the next 30 days, Palmer got $1.2 million and started her own music career.

The video Palmer recorded is a good illustration of the power of storytelling. Although history, storytelling has influenced human actions – for good and bad. And it’s not a surprise. Powerful stories enable ideas to stick and can sway people to make a move. Anything you see an effective leader, probabilities are you’ve also seen a storyteller.

However, this is the thing: making fascinating stories isn’t a talent given from above. It’s an ability anybody can learn, and you can begin it learn it at the moment. In this book, we’ll explore the neuroscience of storytelling and see historical and modern illustrations of great storytellers.

Chapter 1 – Our brain is hardwired to see stories more engaging and memorable than basic statements.

Several years ago, Jacques Prévert a French poet came across a blind beggar in the street. Jacques asked the beggar how things were. The beggar answered with bad– he hadn’t heard one coin get into his hat the entire day. Jacques who was a poor writer didn’t have any money to offer; however, he proposed to rewrite the sign that described the beggar’s condition. After two weeks, the men met each other again. Things had gotten better. The beggar said people were generous now, and his hat was usually full.

Therefore, what was written on the beggar’s sign by Jacques? “Spring is approaching; however, I won’t see it.” How come this helped make people more generous to the beggar?

The solution is also the main message in this chapter: The human brain is hardwired to see stories more engaging and memorable than simple statements.

Think of a high school health class. The teacher mentions data about drug-related deaths and deduces that drugs are harmful. Next door, his coworker takes a different method. She shows a slide of a handsome teenager and presents the class to Johnny. She says to them that he was a good kid, however, he had issues at home and began using drugs to make himself feel good. Then, she shows a picture of a man that looked sick with missing teeth – it’s Johnny ten years after. She deduces that drugs are harmful.

Which of the classes is more memorable? The second class, right? This is the reason

Neuroscientists have a popular saying that “Neurons that work together, wire together.” What this signified is that when numerous aspects of the brain are working together, we’re very more likely to recall as a result that cognitive work.

For instance, logical statements such as “drugs are dangerous,” engage only two aspects of the brain – those in charge of language processing and understanding. When we listen to stories, in contrast, our brains fire up just as switchboards. All of a sudden, we’re also processing feelings and pictures, visualizing sensations, and using the aspects of the brain that’s accountable for cognitive planning.

Now reflect back to our high school illustration. In the first class mentioned, students processed abstract statements and numbers – work the human brain can finish easily; but usually find it hard to remember. But, in the second class, students were providing their gray cells an actual workout. They were busy imagining the specifics of Johnny’s life, thinking of how his issues compared to their own and questioning themselves if they would also use drugs if they were situations.

This torrent of neurons allows the second lesson very more “sticky.” Regardless of their decisions, these students will probably reflect back to poor Johnny if they’re ever given drugs.

Chapter 2 – Great stories need to be relatable and they also need to be both novelty and tension.

Both Jack and Jill were neighbors that lived next to each other and childhood friends. Afterward, they fell in love with each other. There were no romantic opponents to separate them, and both were glad to remain in their hometown. The got married eventually– it only made sense. Their families believed it was a perfect union. They stayed happily ever after.

Is this a sweet story? Definitely. Is it a good read? Totally not–as a matter of fact, it’s absolutely boring.

The main message here is: Great stories are relatable and need both novelty and tension.

The majority of us are narcissists; we like stories about people similar to us.

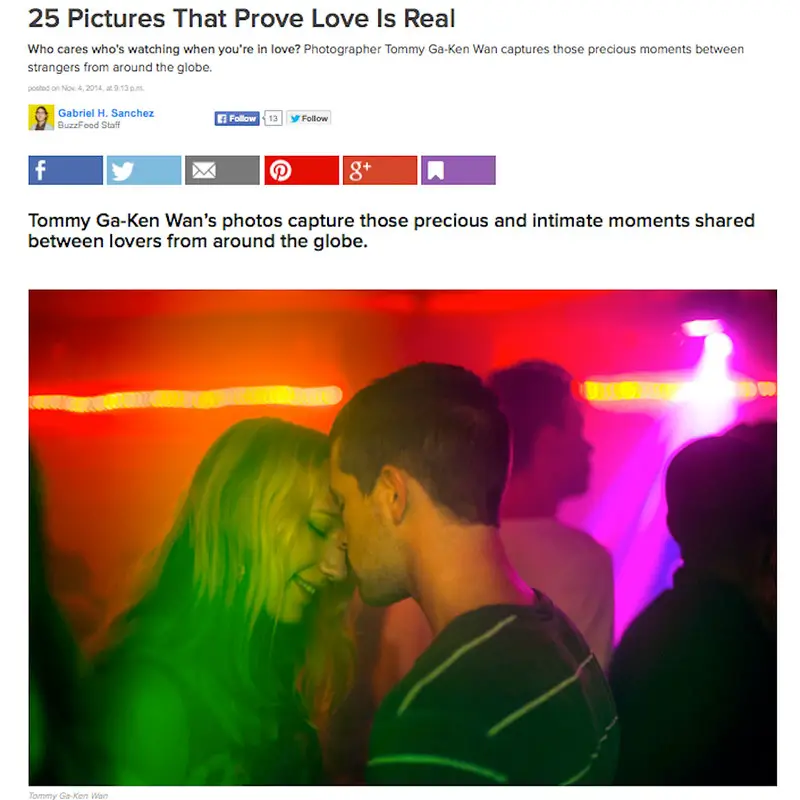

This is the reason why a lot of people read hyper-specific Buzzfeed listicles with titles such as, “21 things that could only occur at Stanford” or “25 things you’ll know if your parents are Asian.” A lot of people fell in love with Star Wars due to the same reason. From the quiet kid with great dreams to the bickering robot couple C-3PO and R2-D2, everybody can see a representation of themselves in the movies’ cast of relatable characters. On the contrary, our Jack and Jill story is really unrelatable: things typically aren’t that simple.

Although, relatability alone isn’t sufficient. Anybody who understands how it feels to be a teenager in a small town or to fill the shelves in a store can sympathize with Luke Skywalker’s life when we first see him. However, nobody is going to use hours looking at him working his boring work on an isolated planet! What this promising setting doesn’t have is a novelty.

In order to keep the audience engrossed, Skywalker has to go on an adventure. The reason we remain engaged is down to evolution. Scans reveal that our brains brighten up when we’re met with something completely new. We owe this reaction to our forefathers, who stayed in a world filled with strange threats. If you weren’t vigilant, probabilities were you’d become dead. Millenia after, that same nature describes why we see movies about exotic societies in distant universes really captivating – we can’t help than to concentrate on the screen

Also, there’s tension. The Greek philosopher Aristotle claimed that great stories, create a space between “what is” and “what could be.” Storytellers close and reopen this space regularly, and this is what forms tension. Consider Romeo and Juliet. The circumstance looks like Jack and Jill’s; however, nothing is boring about Shakespeare’s drama. The whole thing in the starstruck lovers’ world works against them understanding what could be. Every step forward shows new difficulties, driving the characters and the audience toward the story’s tragic ending.

Chapter 3 – Great storytellers need to value fluency more than complexity.

If you run Ernest Hemingway’s work with a reading-level calculator, you’ll immediately realize a strange finding– he writes the same way as fourth-graders. That’s correct, the great Nobel Prize-winning American writer’s language is no more complicated than the one of a regular ten-year-old! Do the exact exercise again severally with books from J.K. Rowling or Cormac McCarthy, and you’ll discover related findings. Therefore, what’s happening here?

The main message here is Great storytellers need to value fluency more than complexity.

The authors got obsessed with this reading-level test. After attempting it with Hemingway and other popular novelists, they began running anything they could get on with their calculator. When they were checking scientific articles or bestselling fiction, the findings was usually the same. Averagely, the most greatly respected authors on any particular topic wrote at a lower level than their colleagues.

If that seems counterintuitive, attempt reasoning about it this manner: these writers value fluency and not complexity.

Fluent storytelling is essentially about moving your audience along and leaving anything that hinders in the way of achieving that. This isn’t only what writers do, though. Think of the cinema. The editors who did Star Wars made George Lucas’s story very energetic by using a mixture of fast cuts and fast transitions. Back then, during the late 1970s, when the first-ever Star Wars movie was produced, science fiction was related to dramatic pauses, slow action, and ponderous shots. The work of the editors’ work transformed that for good and launched the fast-cutting production values we associate with the genre we have now.

This transformation worked for the exact reason Hemingway’s sparse writing style is really effective. It focuses the audience’s attention on what is actually important– the story. When you see or read a fluent storyteller, you’re not making use of your brainpower to ponder on vocabulary or to figure out the importance of lasting 40-second shots. Rather, you’re concentrated on the dramatic tension, characters, and relating to a theme. Eventually, this makes very easier to understand information.

This is the aim of storytelling. Maye, you’re describing a funny story in a bar, writing a TV script, or saying your story in a blog post, your work is usually the same: to go from one aspect of the story to the other as efficiently and easily as possible. This isn’t a thing people will praise you on if you do it effectively, either –however, that’s sort of the point!

Chapter 4 – Stories enable us to care about people that are part of our tribe.

A few past years ago, scientists told a group of people to watch a film of James Bond while putting on a medley of gadgets monitoring their heart rate, perspiration levels, and brain activity. When the hero of the movie saw himself in a jam, their hearts started racing and their hands turned sweaty. They expected that. However, they also discovered another thing. Anytime Bond was in danger, the brains of the people watching the movie started producing a neurochemical know as oxytocin – a type of “empathy drug.”

Oxytocin says to us that we should care about a person. This is an ancient evolutionary reflex. In ancient eras, this neurochemical assisted our ancestors to determine if a person in the distance was a friend or an enemy who might steal their mammoth steaks. Meaning, oxytocin enabled humans to know members of their tribe.

The key point here is: Stories enable us to care about people that are part of our tribe.

Therefore, what is the reason why our brains begin to produce oxytocin when we see James Bond trying to stop a dastardly global scheme? The answer is because we view him as one of our own. Then, this is buttressed by the story being said. The more we see the movie, the better we understand Bond, which enables us to care more about his destiny. That, ultimately, makes us continue watching. When you look at it in this setting, stories assist you for empathy.

Although, this understanding isn’t only about cinema. Think of politics. In 1963, a lot of Americans from various backgrounds gathered in Washington, D.C. They gathered in the streets after listening to stories about people such as Rosa Parks, whose experience talked about the injustice of discrimination. These stories transformed the manner people viewed their fellow citizens and enables them to care more to fight for their civil rights.

The exact belief holds in business. During the late 2000s, the Ford Motor Company was striving. Consumers considered its once-iconic, all-American automobiles as cheap also-rans compared to the newest Asian imports. The only means Ford could change things was to say a story.

Ford created a documentary that started by accepting that the company had flopped– its cars weren’t what they used to be. After, the film then presented viewers to the people making and building the next generation of better-quality automobiles in Ford factories across the United States. These people can be known by anybody– they could be your family, friends or. In a nutshell, they were members of the viewers’ tribe.

It was the first phase in Ford’s long way back into Americans’ hearts.

Chapter 5 – The way you publish is as significant as the thing you publish.

Italy of the Sixteenth-century was a stormy place. Rich families competed for power and schemed against each other. Gossip was a significant weapon in these battles, and it was during that time that the world’s first mass-media business emerged – avvisi or gossip rags. Every day, writers spread across cities such as Milan to get gossips, which they would then write on fancy new printing presses and posted across the city. Avvisi was popular; however, there was an issue: writing by hand was faster.

The main message here is: the way you publish is just as significant as what you publish.

The people of Milan liked gossips, and that allowed them to be really impatient. They liked pamphlets that are written by hand that same day instead of waiting until the following morning for a neatly-printed form of the scandalous stories. To continue in this fast-paced market, avvisi writers had to improve their product.

That is precisely what they did. In time, every gossip blogs/magazines were hand-written and posted that same evening. The message here is: forming a good audience base usually follows a guide, and it requires three phases.

Firstly, you make your content. In Renaissance Milan, this entailed running around churches, taverns, and marketplaces, gathering scandalous rumors, and printing them. Nowadays, that’s as easy as writing a blog article. The second phase is to relate to your audience. See this as sticking your product to a metaphorical door or lamppost where people can view it

The final phase is that you improve. Does changing from a difficult medium such as the printing press to a simple substitute such as the quill enhance your reach? Or, let’s use an illustration of the twenty-first-century, do your viewers like a smaller number of longer social media posts or a larger number of shorter posts?

This third phase is essentially about collecting data. Learn from Upworthy, a content-sharing site that was created in 2012 that turned to the fastest-growing media company in the world.

Upworthy’s idea was easy: take motivating content created by others that had flown under the radar, rebrand it, and post it on Facebook. Upworthy would then determine if their form of a story did better than the original only. Did more people view the entire video, or did more people repost it? By utilizing that research, Upworthy then tried lots of various kinds of packaging until it had the best product. It was a perfect plan to grow their audience, and it enabled Upworthy to develop five times more than any other type of media company in history!

Chapter 6 – When you have content everywhere, it is beneficial to go deep.

During the late nineteenth century, America was packed with stories. Large towns such as New York were home to lots of almost the same newspapers. But, people’s concentration was limited; therefore, publishers made use of the past years form of clickbait – sensational headlines basically shouted at passers-by on crowded street corners. The method sold papers; however, it didn’t get readers’ loyalty. Then, it was high time for a different tactic.

The main message here is: When you have content everywhere, it beneficial to go deep.

The owner of the New York World, named Joseph Pulitzer was a determined man. He didn’t want to work on one of New York’s numerous newspapers – he wanted to operate the newspaper read by New Yorkers. in order to do that, he required devoted customers ready to subscribe to his publication and sacrifice reading those of his rivals. That was a hard sell. This wasn’t only a market in which people said words such as “I’m a New York World type of guy” or “I just read the Journal.” Pulitzer had to make his product different. However, how?

The solution showed itself in the form of a young female reporter called Nellie Bly. Journalism was commonly seen as a man’s work as of then; however, Bly didn’t let that discourage her. One day, she walked into Pulitzer’s office and made her pitch. It was a solid pitch, and Pulitzer employed her. Bly’s writing would be a game-changer for journalism in the United States.

Different from her peers, Bly wasn’t concerned about following headlines on intense shoot-outs and desperate suicides. She wanted a thing more important. Then 1887, she acted as if she was crazy and had herself put away in one of the city’s notorious asylums. For ten days, she kept her cover and collected evidence. When they released her, she had a remarkable multi-part story of corruption, cruelty, and neglect.

It was an awareness and that made the whole country modify mental healthcare provision. Desperate to read the newest part of Bly’s story, New Yorkers also started doing something they had never done before – reading only one newspaper. By engaging with a severe subject in detail, Bly assisted introduce the age of subscription journalism and change the media landscape completely.

In the era of Facebook and the ceaseless churn of superficial content, Bly’s illustration stays as significant as ever. What is her lesson for nowadays content creators? When your market is ruled by producers concentrated on quantity, your best stake might only be to give emphasis to quality.

The Storytelling Edge: How to Transform Your Business, Stop Screaming Into the Void, and Make People Love You by Shane Snow Book Review

All of us are hardwired to see stories more memorable than real statements. The reason is that storytelling engages more aspects of our brains than abstract language does. Maybe it’s Hemingway novel or Star Wars, great stories connect this evolutionary feature by stressing on tension relatability, fluency, and novelty. However, effective storytelling isn’t only about what’s written on the page or what is shown on the screen. For you to influence your viewers, you have to take note of how you’re passing your message across. In this present information-filled world, the best method of doing that is to give emphasis to quality instead of quantity.