Humans are intrinsically malicious. Just check out the newscasts. We brawl. We swindle. We kill and lie and thieve. Our horrible instinctual drives are only kept under control by the government through laws and rules, and penalties for each felony.

Only the egoist ones – the people who are full of themselves – go upfront, in a world like this. It’s cutthroat out there, and only the best will pull through.

But hold up a minute. Is that truly what is happening? Or is this just a story we’ve been telling ourselves for ages, a deception that we have internalized fully enough to take it as a fact?

If you take a look at the most recent scientific findings from archeology to criminology, you’ll find a totally dissimilar story. We are not awful. We are not egotistical. And in case you do not accept it, this outline is here to tell you diversely.

Chapter 1 – Emergencies such as war don’t necessarily make us brutes.

Are you aware of the common thing that Josef Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill have other than having names mentioned throughout history? Each one was under the effect of the same novel: Psychology of Masses, from a writer from France, Gustave LeBon.

During emergencies like war, populations panic and eventually return to their own selves, which are severe and selfish as Le Bon tells in the book. That’s to say when people’s lives are at stake, they become brutal, they care about anything but their good.

Hitler had the thoughts of Le Bon’s in 1940, while he was sending three hundred forty-eight Luftwaffe aircraft to London. He assumed that in a bomb shower, the inhabitants in London would panic and act mercilessly and help their own defeat.

Things really occurred at the time the bombs started to drop and they came as a shock.

Within the last year of the German Luftwaffe ‘Blitz’ that murdered over 40000 individuals just in London and crushed whole streets, the people of Britain desperately built crisis asylums to get ready for the expected panic.

Yet these stayed empty. Incalculable observers have defined how British people continue their everyday lives virtually ordinarily, although airstrikes have been going on for a long time. Kids played, customers bargained, and trains kept working. Despite the windows broken by bombs exploding one after another behind them, the Londoners had their drink relaxedly.

In addition to the fact that the Londoners remained surprisingly untroubled in several aspects, they were finer than ever in terms of psychology and mental health as well. Naturally, there was terrible sorrow and profound grieving. But overconsumption of alcohol diminished and fewer individuals had killed themselves. At the time that all came to a halt, numerous Londoners even missed wartime due to the broad comradeship and unity it caused. Society supported each other much further than they would ordinarily do.

To summarize, the inhabitants in London challenged Hitler’s predictions and proved LeBon’s hypothesis wrong.

The existential risk not in any way revealed the most exceedingly bad in people. On the opposite, this enabled them to be less egotistical. As opposed to Le Bon’s thesis, the Blitz emergency has reinforced British people in numerous ways. Hitler had reached the direct contrary from his aim.

Chapter 2 – The thought of humans’ being fundamentally selfish remains.

You’ve without a doubt heard the motto “Keep Calm and Carry On.” Currently, it’s printed on lots of T-shirts and glasses, unendingly repeated on and mocked. But were you aware that it was initially formed by the British Ministry of Information to protect British morale during the Second World War? Posters supporting unfaltering endurance were published by the millions.

Nowadays, lots of people think that adaptability is a stereotypical part of the British persona – and that Britons’ placidness during wartime was the evidence of this. Yet in reality, the feature is a humanistic one. Several other instances verify that people don’t relapse to primary urges. They don’t even panic when faced with a calamity. After the September 11 strikes on the Twin Towers, for instance, believably self-centered New Yorkers endangered their own lives again and again to rescue the lives of others. The crisis strengthened unity, not brutality.

History has repeatedly shown that extreme conditions have brought out the greatest of us. For instance, the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware was able to conclude, on the grounds of 700 fieldwork, that we act much less egoistically after catastrophes. Following the catastrophe, the number of murders, burglaries, and rapes is usually reducing. But in spite of these truths, the idea that people become wild under such circumstances is still prevalent.

After Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc in New Orleans in 2005, newspapers wrote frightening titles about “gangsters” stealing and killing toddlers. The governor of Louisiana deduced in a press conference that Katrina unearthed the human nature that was swept under the carpet. He said catastrophes brought out the worst in humans and his speech spread around the world.

But as the dramatist journalists left the city and the news cycle continued, it became clear what actually went on: the public had not surrendered to anarchic, unsociable actions. Sociologists have found that most individuals in fact act pro-social. The looting happened but most of the time that was run by groups like Robin Hood, who used the loot of food to keep themselves and other individuals alive – in some cases even teaming up with the police. So Katrina affirmed the latest scientific discoveries that strongly point that people are considerate, not selfish.

However, we stubbornly stick to our negative perception of humanity. This was shown in a 2011 research by two American psychologists. Within the research, the analysts had subjects assessing a variety of cases in which people aided others. For instance, they showed someone who brought a dropped wallet back to its owner. Participators surprised the psychologists by frequently accusing those who helped of having selfish drives. Even when the researchers presented statistics to subjects that showing the wide majority of people never hid the wallet for themselves, many people kept on believing that the action should be selfishly motivated. Negativity prejudice appears to have a strong impact on our vision.

Chapter 3 – Newscast and fictitious tales make our view of the human essence worse.

Whether you’re on the left or the right side of the political scale doesn’t matter; just about everybody has a gloomy viewpoint on humanity. But why do we perceive the world so badly? Why do we assume people are essentially self-centered? The explanation can be seen where the majority of us get our information: the newscasts.

An incident is commonly thought to be worthy of being broadcast on the news on the condition that it is unusual – and in a majority of the cases, this implies extremely catastrophic. The news is a display of misfortune and pain: a violent act here, a natural disaster there. You’ll not see a title saying that war has not been started in Europe today, ever.

The effect of all this negativity is anticipated fairly. It makes people pessimistic.

The news carries bad connotations in its essence. Every day we are exposed to tales that reinforce our faith in evil. The impact of this on us is like nocebo. Nocebo is similar to placebo but negative. Once you take a placebo, you hope that it will have a great positive impact on your well-being, even if it actually only includes sugar. And this belief can truly have positive effects. Nocebos have just the opposite effects. When you take one, you await it to have a bad effect – and you may well feel worse as a consequence. The news is basically a ruthless intravenous drop of nocebo released into the carotid artery of the society.

Not just the newscast has a nocebo impact on our vision. Fabrication has the ability to strengthen our dismal self-image, as well. For instance, Lord of the Flies, a novel that paved the way for winning its writer, William Golding, the Nobel Prize.

Golding wanted to create a “real” story about how kids would act if they landed on a deserted island. In the story, chaos flares up and many kids lose their lives. He was congratulated for a nominally sensible description of what people are truly like without the power of law to stop them from striking each other.

Rutger Bregman had suspicions about the elemental fact of this story. He questioned what kids would actually do if they were left isolated on a desert island. He searched for a true Lord of the Flies story and came across a 1966 record of six children stranded on a distant island in the South Pacific for 15 months.

But these kids didn’t perform just like the children in Golding’s book. In reality, chaos didn’t win. The kids made an agreement to permit no fights. Furthermore, they succeeded to light a fire and keep it burning for over a year, and they continued their friendships long after their rescue.

Then which tale shows the reality?

Chapter 4 – People are not bad by nature.

Is the touching case of the original Lord of the Flies an extraordinary case – a life-giving exception to the discouraging rule? Or is there truly something that defines whether we act well or wrongly when isolated from society?

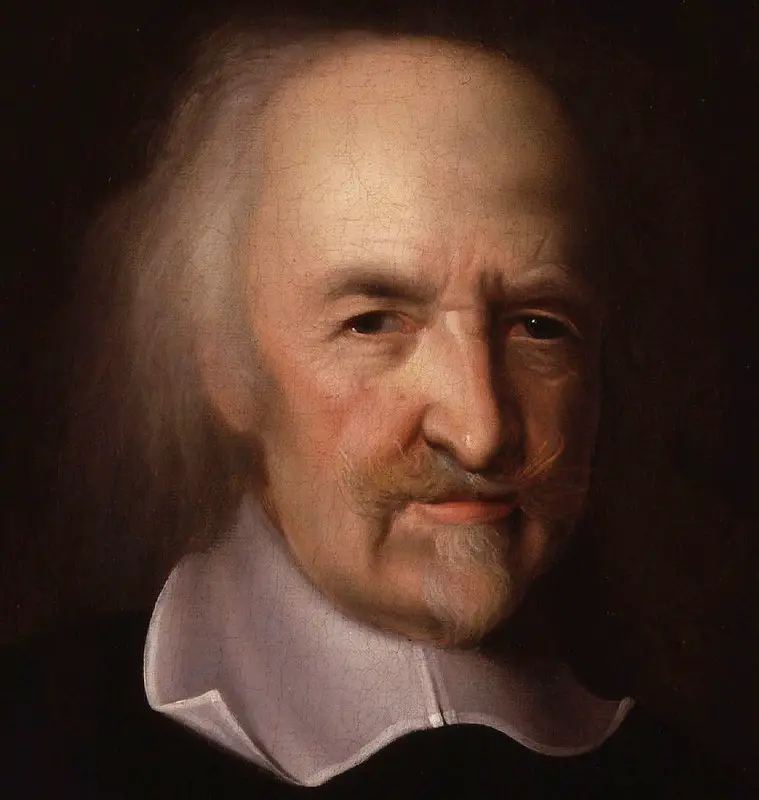

Philosophers have dealt with this issue for ages. The seventeenth-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes presumed that individuals in their genuine nature are “bad” – they perform only in their own self-concern. He thought that without governmental, orders, and laws, mankind would be in a permanent “war of all against all.” As we have seen, this worldview is still common today.

Though unlike Hobbes, we’re presently in a circumstance to go way ahead of the philosophical hypothesis. We have proof from different disciplines that suggest a more experimental illustration of human life before the rise of civilization.

Till lately, both fieldwork and archaeological diggings appeared to verify Hobbes’s vision of the world. For instance, The US anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon examined the hunter-gatherer Yanomami society inhabiting in the Amazon area. In his 1968 publication, The Fierce People – the best-selling anthropological book of all time – Chagnon proposed that the Yanomami were in war constantly.

Psychologist Steven Pinker’s 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, shows a numerical statement of the Hobbesian aspect. On the grounds of dug skeletons, Pinker pointed that in ancient times about 14 percent of people must have been sacrificed for war; in short, they’d been killed. In recent times, the global murder rate, despite the constancy of war, holds at one percent. In keeping with Hobbes’s custom, Pinker settled: “It was the only civilization that was able to tame the warlike barbarian in us.”

However, both Pinker’s result and Chagnon’s thoughts about the Yanomami were not perfect. For starters, the Yanomami does not represent how our pre-civilized forefathers lived. When Chagnon issued his book, the Yanomami had been in contact with harvesters and modern city people for a long time. It was also unveiled that Chagnon gave them axes and sickles during fieldwork. He later claimed they were pretty savage.

And Pinker’s calculations? They’re basically wrong. 20 of the 21 diggings he mentioned, which drove him to determine a 14 percent homicide rate among hunter-gatherers, arrived from a time after farming had been flourished and people had stopped moving from a place to a place. Hardly healthy proof to confirm the Hobbesian assumption that pre-civilized people were wild!

Chapter 5 – Human advancement isn’t dependent on the survival of the most adaptable but the survival of the foremost affectionate.

And so the question persists: How did we actually act and live prior to civilization- in other words, before we became permanent inhabitants and started farmland almost ten thousand years ago? To reply to this question, why not turn our heads to the Stone Age data collectors– the masters who draw fact and fiction, history and legend on that centuries-old canvas, cave wall?

Cave drawings give an idea about the livings of our wandering predecessors. However, no nomadic cave paintings were found to show destruction or battle. Hunting scenes, though, are described often- so brutal deaths demonstrated by skeletal residues not certainly prove human violence. Fights with animals may likewise simply caused that.

Anthropologists working on our history presently believe that violence between nomadic hunter-gatherer communities seldomly happened. Rather, they blended, acted collectively, and learned from each other. Those who were especially great at collaboration had the greatest odds of survival and had the most kids. Life didn’t choose the most powerful or the most self-centered but the most collaborator.

Yet it’s not adequate only looking at cave drawings and skeletal residues when making inferences. Our heads and physical structure also contain signs to confirm this hypothesis.

Surprisingly, our friendliness is proved by our facial properties. The appearances of modern people are usually more delicate, rounder, and “more adorable” than the looks of our predecessors. That is to say, humans have tamed themselves. Similarly, the evolution of dogs, we’ve been chosen for our adorable faces and friendly characters. We’ve become what Bregman refers to as Homo puppy.

Our eyes are too proof of our ultrasocial creation. In the animal realm, we’re exceptional for displaying the whites of our eyes. This enables others to understand precisely where we’re leading our attention, which allows reliance and collaboration. Other primates, with their colored eyeballs, have much more efficient poker faces.

The continuation of the friendliest is apparent not only in our presence but also in our minds and the way we understand. Personally, we’re not so intelligent. Comparisons between monkeys and babies prove that we only do better in one section of intellect, “social learning” – in which we exceed chimpanzees and orangutans by a great amount. We’re so skilled at getting information from each other that one could tell cognitive capacity and cooperative skills are two sides of the same coin.

Chapter 6 – Civilization made people wild.

So we’ve decided that the Hobbesian view can’t be right. How, at that point, did Homo puppy ended up wild within the first place? Because – and this is the elephant in the room – it can’t be rejected that we are, in spite of our puppyish properties and natures, able of performing brutal actions.

Let’s view the history of philosophy once more. Almost a hundred years after Hobbes decided that human creation is base and brutal, the French Romantic thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau decided the opposed outcome. In his way, humankind isn’t naturally bad and defective. It’s essentially good but was damaged by culture.

Latest archeological studies declare that, near the end of the first ice age, when communities became more settled, people started building the first military reinforcements. About this identical time, bowmen started seeming in cavern murals, and dug skeletons from the time really do show obvious proof of human destruction. And, if you consider it, it’s notable apparent why we converted wild: there was now land to battle over and products to protect. In sum, people abruptly owned premises.

Premises made us doubtful about other individuals. Earlier, when we were still hunter-gatherers, there were looser judgments of what belonged to whom. Where we belonged was too unclear. Wandering hunters and gatherers had no rigid tribe. They would meet different groups and effortlessly mix with them. All this is gone when people started settling down. We developed from meandering cosmopolitans to suspicious xenophobes.

The rise of violence can be connected to the improvement of hierarchies within cultures too. Before the founding of great and crowded settlements, leaders found it hard to remain in control, because wandering life didn’t let inequality to take place. Paleoanthropological prooves proposes that hunter-gatherer societies grew shame-based systems to hold people in line; whenever someone tried to dominate others, the society would use embarrassment and peer pressure to pull the person back down to size.

But with the appearance of settled societies about 10,000 years ago, important persons couldn’t be dethroned with a little chatter and teasing anymore. Rulers could quickly assemble fighters around them, which served to reinforce their authority. And now that leaders control large armies, it’s not like they can be dethroned simply by humiliating criticism or tweeting.

Chapter 7 – Our room for empathy has a bad side too.

Perhaps all of these statements seem very reasonable to you. Science is just confirming what numerous have thought all along – that people are fundamentally good and would prefer not to hurt others. So how can we frame this with the cruelty of history like the Holocaust?

Well, the response to this is covered in different problem – a question that Allied scientists questioned in 1944: How could it be that even in the appearance of direct loss, German warriors stayed in the fight? Actually, the study showed that German Wehrmacht warriors fought nearly twice as effective as Allied soldiers. Even their abandonment rate was approaching zero. This confused the Allied researchers. What was happening to the Nazis?

One of those scientists, the American sociologist Morris Janowitz, had been sent to discover why the German warriors fought so stubbornly, in spite of being extremely outnumbered and completely surrounded. Similar to other psychologists of that period, Janowitz could only explain their situation in one way: the soldiers were under the influence of an idea, programmed to love the homeland in an obsessional way.

Allied powers tried to battle this belief with the propaganda of their own. The Psychological Warfare Division dropped incalculable brochures over the German region, each with the same message: Your position is hopeless! The Allies will prevail! But it didn’t work. The Nazis disregarded them. And why? Since the researchers’ presumptions about the Germans’ inspirations were all wrong.

It wasn’t until Morris was given the opportunity to directly ask questions to the captured German soldiers that he realized that they had not been brainwashed. They fought very hard because they didn’t want to desert their neighbors and friends. Most of the German soldiers were not fanatically committed to the Nazi cause. They were just comrades and good friends. The Nazi generals understood this well and made every effort to develop camaraderie in their units.

So, can even violent criminals be motivated by unity and dedication? Judging by the motives of the Germans during World War II, the answer is clear. Yes. They were guided by compassion, a very human emotion. It may seem counterintuitive, but our ability to empathize sometimes prevents us from seeing the suffering of others.

After all, we can only relate to a few people. It is similar to the zoom function of the camera. We empathize with those around us-those we can smell, feel, and hear. However, with this, a lot is lost. It’s worth recalling that empathy eventually leaves out more people than it embodies.

Chapter 8 – People run away from aggression whenever possible, even in vital situations.

Compassion has two sides that are separated into two ways. This makes sure that we are battling for our family, friends, and neighbors. However, it also allows us to murder them. Once it is a matter of life and death in the war zone, we leave our friendly attitudes and turn to aggression – we often think so.

However, this thought is also wrong. We don’t become wild animals on the battlefield all of a sudden. Even in extraordinary conditions like a battle, it is usually very difficult for people to pull the trigger and kill others when they face the enemy.

One of the first to examine this effect was Samuel Marshall, an American colonel, and historian. In 1943, Marshall with his battalion of 300 people tried to conquer Japan’s Macin Island. In spite of their excellent training and number of people, they failed. Marshall was astonished and decided to scrutinize.

Marshall interviewed his soldiers and urged them to be frank, in a way that was unusual for the military. What he found is amazing. Only 36 out of 300 soldiers used weapons. Whether successful or not in training, all soldiers were not sure whether to shoot.

Also, the statistics of British soldiers’ deaths during World War II are saying something. Most of them – 75% – died because of either bombs or mines. That said, relatively few people were shot by those who had to look into their eyes. And stabbing them is harder than shooting them. In the Battle of Waterloo, bayonets were attached to tens of thousands of rifles, but less than 1% of the wounds were caused by them.

TV shows like Game of Thrones might suggest that it’s easy to kill someone else. However, this is not true. Most people have a deep hatred of murder.

We see this in a famous event during World War I. Surprisingly, on Christmas 1914, the Germans and British troops violated orders and stopped fighting. Rather, they drank together, gave gifts, and sang Christmas carols in the trenches.

The commander had to force the soldiers to continue the battle. Nevertheless, the soldiers reassured that they would be aiming too high at each other, continuing to secretly send messages to each other about when the next attack would occur despite the imprisonment or worse threats.

Chapter 9 – We need a new and more realistic vision of mankind.

As we have seen, there was no war until civilization. The hypothesis that the crust of civilization disappears as soon as we are in a survival state is all wrong. We often don’t use aggression even when it may make sense, for example, war. So we are not as malicious as we believe. If you can acknowledge it, you can create a new and better community.

However, as long as we keep on thinking that people will act morally only if there is a punishment, then of course there will be results. You will have to imprison more and more populations. As can be seen in the United States, prisoners are often trapped in cage-like places and may only be let out for an hour a week. We need to ask ourselves. Does such an act really cure people convicted of a crime? Does it really contribute to moral behavior?

Norway’s Halden Prison proposes a less punishing approach. Each inmate has their own spacious room with a flat-screen TV. In Halden, there is no regular food in the cafeteria. Inmates cook themselves. In their spare time, they can go to the prison’s recording studio or to climbing walls, and if the weather is fine, they can enjoy a barbecue with the guards in the evening. The guards don’t even have guns.

“Can this be real? one may ask. Do Norwegians get a reward for committing a crime and then stay in a quiet comfortable place which is called prison? The author thought this until Tom Eberhardt, the prison chief, asked him a basic question: Who would you rather have as a neighbor – someone who’d just been released from a typical American prison, or someone who’d been released from a modern Norwegian one?

Statistically, the response is obvious. People residing in vulgar prisons become like time bombs. In the United States, with one of the highest in the world, relapse into crime rate is 60%. However, among people who stay in the Norwegian prison Bastøy, which is like Halden, this rate is only 16%, making Bastøy the most successful prison in the world. Norwegian prisons spare a lot of money every year because the recurrence rate is much lower.

What the Norwegian model tries to convey is that if we treat the prisoners as if they are responsible, they will acknowledge that. And this seems to work. When we assume that the majority of people are good, everything alters. If we can do this, you can start reorganizing not only prisons but also businesses and schools. – maybe the whole government.

Humankind: A Hopeful History by Rutger Bregman Book Review

For many years, we have fed the wrong idea that people are instinctually selfish. Thus, we often don’t trust each other. But it is not civilization or sanctions that keep us away from aggression and egoistical acts. From an evolutionary point of view, we are not selfish or killers. We are kind and willing to cooperate, as the way we act in crisis shows. We now need a new and more positive outlook for mankind.