All business owners and CEO understand the significance of workplace culture, even if they might find it hard to explain it. Establishing the appropriate setting for people to work in and ensuring that the whole company does their work with the appropriate attitude can be just as essential– and just as hard– as creating the perfect product or making the perfect investment.

However, culture isn’t something exceptional to the modern world. As a matter of, there are things to be acquired from some of history’s great leaders – even the ones who look far removed from the field of business. This is the reason why this book doesn’t only take in instances from Amazon and other modern giants – they also went back to time to look at historical leaders and people who changed cultures in unforeseen places, from 12th-century Mongolia to a Michigan prison.

Finally, forming the ideal culture for your business boils down to you, since all culture needs to reflect the details of the company in question, and the people who manage it. These book chapters have some great guidance on understanding out what that perfect culture is and how to make it function.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks

Chapter 1 – Culture is vital – and it’s unique to every flourishing company.

It’s normal for business leaders to state that culture is important to a company’s success. However, ask for further detail, and the reply is regularly vague. What is culture precisely, and why is it really essential?

Let’s begin with what it’s not. Culture is different from values – values are similar to aspirations, whereas culture means something in practice. Also, culture isn’t the character of the CEO: that can just ever be one part of it.

In addition, culture differs greatly from one company to the other. Compare Apple and Amazon: Apple places such an importance on the quality that it used $5 billion dollars on a beautiful new headquarters. While Amazon, is famously cautious – a cost like that would be absurd on the Amazon site.

Culture needs to be an expression of the business itself. The co-founder of Intel in 1968 Bob Noyce, offers an ideal example. He discovered that the growing field of technology, where the engineers were actually driving things forward, required a new kind of workplace setting.

Therefore, he formed a very different business culture that extremely inspired the development of Silicon Valley. There was no vice president in his egalitarian system had; he provided the majority of his workers stock choices; and he sat everyone in one big room, instead of separate offices. Also, he made people attend sessions on what was called “the Intel Culture.” All these formed a culture where concepts could thrive – just what this innovative company required.

A good workplace culture won’t miraculously change your company into Intel. And a bad culture isn’t inevitably a means for disaster. Consider an extremely talented athlete with bad training management: it’s still likely that they’ll prosper based on talent alone. Although, a better food and training schedule, will still assist them to maximize their potential – which is exactly what culture can do to your business.

In these book chapters, a various kind of illustrations from both business and the wider world – extending all the way back to Genghis Khan – will show the various methods in which culture adds to success, and provide you some guidance on defining your business’s culture for yourself. Since culture isn’t a thing that can be generalized; it needs to be your own.

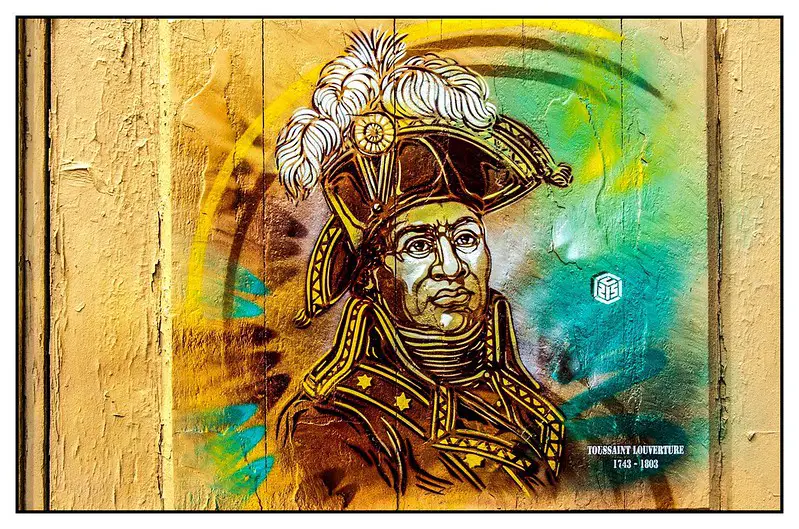

Chapter 2 – Toussaint Louverture understood how to instill cultural virtues in the minds of his army.

The story of the man who eradicated slavery in Haiti might not seem as if it has teachings on contemporary business culture. However, as a matter of fact, he established a culture where you can learn much from.

In 1743Toussaint Louverture was born into slavery in Saint Domingue known as Haiti then. When a revolt occurred in 1791, he was made a leader. He cleverly saw off invasions from the Spanish and the British, and in 1801 he was made the governor and put a stop to slavery.

Louverture had a brain for making huge choices that obviously communicated the values and culture he was attempting to instill in his army. He did that by making instructions that surprised his soldiers and that allowed them to think about the values inherent in the things they did.

For one, he prohibited his officers that were married from having concubines – very rare at the time. What was the reason? Trust. If the wives of his officers’ couldn’t trust them, why then should the army trust them? Louverture’s shocking instructions pushed main cultural virtues –trust was the virtue in this case– to the forefront of his soldiers’ minds.

Also, Louverture was aware that his choices needed to clearly show his cultural priorities. After he took over the island, his army could have easily murdered the previous plantation owners as a payback. However, he made his army know that the key thing was economic survival. Therefore, he allowed his former slave owners to live and even allowed them to continue working the plantations, using their expertise. Prosperity was really essential than payback.

Utilizing shocking guidelines to keep people thinking is only as effective in modern business as it was during Louverture’s era. For example, Amazon sums up its well-known frugality in the guideline “Accomplish more with less.” Before, this guideline was even included in the strict practice of giving workers office desks that were constructed from a cheap door with legs attached to it. This made sure that workers thought about frugality each time they sat down.

Furthermore, in 2010, Reed Hastings of Netflix made a Louverture-Esque choice, confidently showing his company’s changing priorities. Although Netflix was relishing success in DVD rental, he was aware that the streaming revolution was starting. Therefore, he put a stop to inviting his DVD executives to meetings. A hard choice; however, one that delivered a very clear message about the direction the company was heading to.

Modern businesses may experience different problems from Louverture; however, his leadership approach is still standard. The culture he wished for was imprinted in all the things he did.

Chapter 3 – Remember death every time, just like a samurai – it’s helpful for business.

The samurai which is the warriors of ancient Japan lived by a range of cultural virtues called bushido that is still there up till now. Bushido is definitely still applicable when we talk about business culture.

Essentially, bushido isn’t a range of principles; however, a range of practices: it’s basically about actions and not beliefs. In the contemporary world, you would prefer it not to a set of business “values” – the kind attached on a bulletin board, which regularly ends up proving useless–however instead to corporate virtues. Virtues are entirely about what you really do.

The most significant samurai regulation is strict; however, beneficial: remember death all the time. A consciousness of the constant likelihood of death assists you to concentrate and meaning you’ve already acknowledged the worst possible result. In a business setting, that entails admitting that you could go bankrupt all the time or get defeated by a competitor. Accept those likelihoods, and you’ll discover that you’re free to think about more significant problems–may be thinking whether or not your company is an ideal place to work or if you’re proud of your outputs.

The other samurai virtues comprised honor, politeness, and sincerity: three matching attributes that translate well to business. In 2009, when the author created the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz with fellow entrepreneur Marc Andreessen, they accepted that the company’s achievement relied on the entrepreneurs they intended to support. Therefore, they outlined one of the company’s cultural virtues as respecting the entrepreneur all the time. It was a dismissable crime to publicly criticize an entrepreneur.

However, that didn’t entail giving entrepreneurs an easy experience. A different virtue recollected the samurai’s stress on sincerity: tell the truth all the time, even if it hurts. Although, hard truths, were conveyed with good, samurai-style politeness.

When we talk of doing hard things such as conveying hard truths, bushido has some great advice: the reason you do good isn’t as significant as the basic fact that you do. Irrespective of your motivations, the only significant thing is that you behave appropriately. It’s our deeds that define us.

Remember that, and if you actually die now– or if your business permanently shuts down– you can still reminisce on it with pride, as a samurai would.

Chapter 4 – Shaka Senghor made an incredible cultural change while he was in prison, proving great leadership.

Shaka Senghor would likely have been a good samurai, and there are things anyone in modern business can learn from in his story. At the age of 19, he was imprisoned in Michigan for second-degree murder; however, currently, out of prison and a best-selling author, Senghor has many things to teach us, particularly on how to shape – and re-shape – a group’s culture.

While he was imprisoned, he was the leader of one of the gangs known as the Melanics, which he changed into an organization that operated according to harsh moral principles. After he became part of the Melanics, Senghor found out that they weren’t abiding by their own principles.

He quickly confronted the leaders of the gang on how they treated a member they were stealing money from, indicating that it was against their code to do that. Although inquiring further questions about virtuous leadership – questioning, for example, if a leader is truly a leader if he doesn’t abide by his own rose– he got to the top, as the members progressively agreed to his point of view.

Ultimately, having thought on the pain that was instigated by violence, Senghor understood that he had to amend the Melanics’ cultural code completely. He accomplished this by regular meetings: he ensured that members eat, work out, and study together. Day-to-day meetings are one of the key methods to change a culture. By doing this, the members changed from violence and towards a more ethical way to life.

One significant lesson in shaping group culture is to view things from the perspectives of a newcomer. During Senghor’s early time in state prison, he witnessed as someone got stabbed in the neck, which intensely shaped his outlook of prison culture. First impressions usually have a defining influence, irrespective of whether or not they’re as intense as that. This is the reason why it’s worth talking to new workers directly all the time about their first impressions, to tell if your company culture is shaping people in the appropriate manner.

Also, business leaders need to be as open to change just as Senghor was. The author who is the CEO of LoudCloud, was on one occasion nearly swayed to rewrite the accounts to make it seem like one fairly unsuccessful quarter had improved better than it had. The idea wasn’t illegal; however, it did form a deceptive impression. An advisor told Horowitz that, as trust was one of the company’s main aims, he shouldn’t only be abiding by the letter of the law; however, demonstrating trustworthiness. And that was what he did. As Senghor displayed, you need to walk the talk.

Chapter 5 – Genghis Khan accomplished his success by fostering inclusion and loyalty.

One of the key essential features of any successful culture is a sense of inclusion: everyone needs to feel like they belong there and are working toward achieving common goals. Inclusion isn’t a current invention – Genghis Khan who is a master of inclusion was also the greatest effective leader in military history.

He was born an outcast in 1162, Genghis turned out to be supreme, although cruel, leader of the Mongol tribes, who traditionally had battled severely against each other. Genghis understood that they lacked a common goal – and, in a persistent military campaign, he discovered one for them.

This campaign can somewhat be associated with Genghis’s meritocratic principles. He prohibited inherited titles, and anybody who outshined could rise up. Also, he valued loyalty. When he conquered his opponent Jamuka, he killed Jamuka’s men who had betrayed their leader, as a result of their disloyalty. Conversely, he actively brought in talent from defeated tribes. For example, he made great use of the Uighur peoples’ advanced civilization, sending their experienced workers, such as judges and scribes, all through his empire. Also, he fostered marriage between tribes to incorporate their cultures.

These are clever practices in any attempt, not only during the times of war, and when we talk of inclusion and loyalty, contemporary companies can learn a few things from them.

One illustration of this occurred in 2004 at Frontier Communications. When Maggie Wilderotter was made the CEO, she discovered a severely class-based system in the company: the white-collar staff hardly communicated with the poorly-treated blue-collar staff. Therefore, she sacked the least effective executives, offered every worker a raise, and constantly supported the underdogs in clashes.

Although, It had to go either, though: everybody needed to be loyal. After Frontier got some parts of Verizon, Wilderotter discovered that out close to half of the previous Verizon workers weren’t using Frontier’s product; however, subscribing to the cable companies they were in competition with. Therefore, she offered them a month to change to Frontier – or they were sacked.

The author reformed his own company’s employing process toward better inclusivity by ensuring that people from a diversity of talent pools had a contribution. This led to a company of 50% female, 27% Asian and 18.4% African American workers. Even more essentially, the new employing process has enhanced company culture, with people from various backgrounds adding to their various experiences and strengths. Just like how Genghis incorporated all those various tribes together, the company got the best from everywhere.

Chapter 6 – There’s no secret recipe for forming a great business culture; however, you need to be yourself.

Therefore, let’s talk about that. It’s good to learn from case in point, whether it’s Toussaint Louverture or Amazon, Genghis Khan or Frontier. However, how can you define the culture that’s precisely correct for your business?

Firstly, you basically have to be yourself. And that’s not only good common advice; it’s the only approach to create a successful culture. Being yourself entails understanding your personal weaknesses and your strengths. For example, the author enjoys long discussions– not a perfect trait when he was CEO of a busy software company. Therefore, he ensured he was in the midst of people who weren’t much of talkers like him. That made sure that his less-desirable personality attribute didn’t define his company.

While your beneficial personal qualities should be the basis of the culture. For example, Dick Costolo the CEO of twitter CEO is a very hard worker, which was perfect when he first began at the company. During that point, he discovered that he had to change a culture where people usually left work early. To support staying late, he would go back home for dinner every night and then go back to the office to talk to the people who were still in the office, a really obvious approach of compensating hard work and leading by example.

Also, that is an illustration of how culture has to align strategy: the cultural features you encourage has to align with your business plan. For example, “Move fast and break things” was a great slogan for the early Facebook, whose goal was to innovate quickly. However, let’s assume you’re the CEO of Airbus, it’s not really good advice.

So which virtues should you pick? It’s hard to generalize since they need to come from you and your business. However, there are a few broad points you should think of. Firstly, whatsoever these virtues are your new hires should symbolize them: make you employ people well matched to your culture all the time.

Secondly, ensure that the virtues you decide on are actionable. Just like the samurai’s bushido code, they have to be things you do, not only idealized beliefs. Thirdly, although these virtues don’t need to be completely unique, they need to at least differentiate your company from the competition. If they don’t do that, you’re just like a Silicon Valley tech company who makes an issue out of permitting casual dress – if that’s the default, it doesn’t mean.

When you ponder about successful cultures, then, don’t only consider the virtues themselves: think of their context, how they reflect a leader, and how they match with the organization’s goals.

Chapter 7 – Good leadership needs strong decision-making – and redefining a culture when essential.

Occasionally, a cultural virtue will end up having an unexpected negative effect. When that occurs, it’s essential that the company immediately reevaluates and then amends its priorities. That needs strong decision-making.

For example, Research In Motion, or RIM – the company that created BlackBerry – valued customer satisfaction more than any other thing, and therefore improved their phones with long battery life and great keyboard speed. When the first Apple’s iPhone was created, the sleekly designed newcomer failed in those aspects at first–therefore, RIM didn’t take it so seriously, and overlooked it as a competitor. That showed really costly. The company needed to have demonstrated flexibility and made an extreme choice to re-prioritize based on the new market situation.

An object lesson might have assisted RIM to make the essential improvement; meaning, a shocking caution on what a company’s priorities have to be. Let’s assume, for example, a salesperson does an illegal thing. Sacking them only may not be enough; to place proper importance on abiding by the law, you may also have to sack the people the salesperson reported to, even though they weren’t personally involved.

Strong decision-making is hard, and leaders possess different forms. However, generally, it’s good to strike a balance between empowerment and control: let everybody have a say; however, make the last call yourself. You need to also ensure to use a proper amount of time on each choice: sometimes there’s great value in fast decision-making; however, not all the time. For instance, at the author’s venture capital firm, choices on what to invest in need thorough and long conversation and debate. Fast choices would be counterproductive.

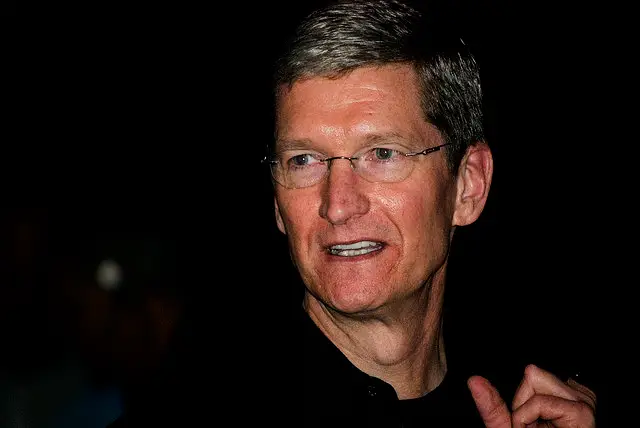

Also, your choices will be influenced by whether or not you run what the author refers to as a wartime or peacetime operation. A wartime CEO has put success ahead of the protocol on occasion and requires to act quickly and aggressively. A calmer, peacetime CEO concentrates more on good protocol and longer-term achievement. Changing between these modes can be difficult, and may need diverse management teams. Apple is an example of a company that’s accomplished such a shift: Steve Jobs was a wartime CEO, while Tim Cook his replacement works in peacetime. It’s been a great transformation.

During times of crisis or calm, it’s up to the CEO to make choices that define, implement or reimagine a company’s cultural virtues – whatsoever these virtues are. Although there are a few, that shouldn’t be far from a CEO’s mind. Let’s look at them in the following chapter.

Chapter 8 – Two near-universal virtues that companies need to keep are trust and loyalty.

Although virtues usually need to be appropriate to an organization, there are a few that nearly everybody would be able to foster, from Genghis Khan’s Mongol empire to a tech company just like Apple. Obviously, they’re particularly hard ones to execute.

Firstly you need to trust. Regardless of the place you work, ensure that your workers trust both one another and you. Also, they need to trust you a lot that they can give you the bad news when it is needed– for example, when there will be layoffs – and still keep their respect. If they don’t do that, bad circumstances will have a routine of only getting worse and worse.

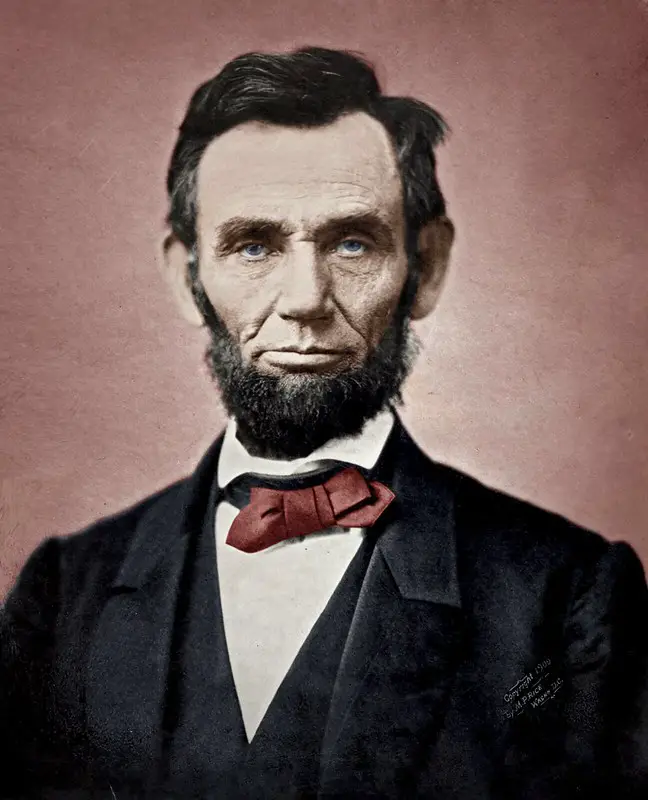

Consider Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. With that speech, Lincoln succeeded to instill the American Civil War with new understanding by revealing the cause why a lot of soldiers had died at Gettysburg. He approved the cost of the war; however, he also explained the reason he trusted in its importance – a model for any CEO.

Definitely, bad news goes either way, and you have to nurture a tradition where you constantly know the worst of what’s happening. Every single organization of important size is home to a lot of issues: your duty is to be aware of a lot of them as possible. Hence, your workers should trust you enough that they can bring problems to you, and understand that you’ll provide positive and constructive answers about them when they bring issues to you. You definitely shouldn’t put a blame on your workers for issues by default, particularly because, at the heart, most arise due to fixable concerns such as prioritization.

Although it is hard to instill, the other virtue you should certainly nurture is loyalty. How do you foster loyalty between you and your workers? Basically, target to keep a good relationship with them: take an honest interest and stay honest. Don’t assume that they will remain with you for life, as that’s uncommon nowadays–however, know that, workers, leave managers more frequently than companies.

Apart from trust and loyalty, your company’s virtues need to be really unique. However, if you remember the advice mentioned in this book– from forming a culture associated with your own personality, to create rules that display your virtues in stark relief – you’ll be on the right path to forming precisely the workplace culture that your company requires.

What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Business Culture by Ben Horowitz Book Review

Never underrate the significance of a business’s culture. Past and current examples demonstrate that culture needs to be much more than only a list of values held to the wall: it has to be a set of virtues that fortifies the whole thing your business does. The reason is that it’s our deeds– what we do, not what we talk of or our emotion– that define who we are.

Define your company’s personal culture.

Your culture shouldn’t only be your product’s best attributes or your own. It has to be the complete tactic that you and every other of your employees bring to work. In order to check if this is the case, create a list of the things that make your company exceptional; afterward, ask yourself: are those features abstract values that you aim for, or virtues that you exercise every time you make a choice? If your virtues aren’t displayed in everything you really do, it is possible that your culture isn’t what you consider it to be.