The summer of 2020 will be remembered by coming generations and historians for two things: the massive Covid-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter uprising that is equally global.

George Floyd’s passing illuminated the latter’s flame, but the powder keg that detonated that summer was years in the making. The death of Floyd was not as protesters saw it an isolated act of police brutality. America has had to deal with a legacy of anti-Black bigotry to understanding his passing.

Although it was made apparent by British protesters across the Atlantic that this was not merely an American occurrence. Britain too has a history of segregation, imperialism, and bigotry all of its own. Far too often, this history is wrongly known or skewed by convenient misconceptions. The treatment of Black Britons as second-class people remains justified by these distortions.

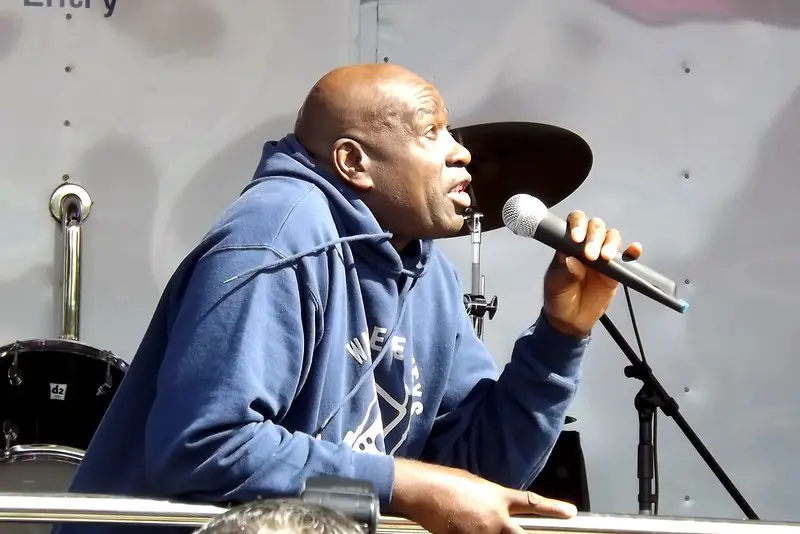

So how can this past be understood? That’s the problem that Akala, an artist, analyst, and activist, wanted to answer. By recording his history of growing up in a Britain that classified him as black, he did this.

We will observe Akala’s story in this review from the age of his ancestors, who came to Britain from their Caribbean colonies in the 1950s. Then we are going to move on to Akala’s youth in London’s multi-ethnic working-class area. We’ll be discussing the intertwined narratives of prejudice and imperialism in Britain along the journey.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks

Chapter 1 – A racial uproar was faced with Caribbeans landing in Britain.

Britain was tired, poor, and in physical rubble by the close of the Second World War. It has faced a labor shortage as well. It needed staff to get back on its feet.

Despite its defeats in the war, Britain already had a large empire. In 1948, the British Act of Nationality was adopted. This granted the right to live in Britain to those born in a British colony. Caribbean subjects holding British passports started arriving at Tilbury, a port near London, with incentives provided.

This was the “age of the Windrush,” a nod to the ship’s name that took many Caribbeans to Britain. They regarded themselves as respectable civilians who had come to help restore the “motherland” devastated by the war. But that was not how they were treated by white Britain.

About half a million Caribbean immigrants, including Akala’s grandmother, settled in Britain between the late 1940s and 1960s. They learned soon that the tales they were told about the motherland were not accurate.

Britain was loaded with lazy white people, for one instance. In the colonies, whiteness was a symbol of strength and prosperity. Before moving to England, the only white individual’s many Caribbean citizens had seen were members of the colonial class. Envision their shock when they saw a white man cleaning the street for the first time. It was preposterous. What was Britain like?

This was not the only shock, though. Caribbean arrivals were told they would be greeted as heroes. When they were greeted with animosity instead they were stunned. For instance, Akala’s grandfather recalls that within a week of stepping foot in the nation, he was frequently called racial slurs in the community. He was not helping to restore the nation as his new neighbors perceived it; he was a freeloader who would come to rob “their” jobs or even “their” women.

How was this finding drawn by white Britons? Well, nobody had managed to demonstrate to white Britain that the then-built common welfare state was primarily funded by taxes collected in colonies such as Jamaica. Nor were they informed that the citizens in those colonies who produced coffee, tobacco, and gold, and who were now moving to Britain, were not “immigrants.” Like everyone else in the nation, they were British citizens.

In the absence of all of these explanations, animosity to the Black people of Britain only tended to escalate.

Chapter 2 – At a young age, Akala knew what it meant to be black in Britain.

Akala was born to a British-Caribbean black father and a Scottish-English white mother in 1983. His father moved from Jamaica to England, and his mother remained in the Hong Kong Colony. Both were descendants of the British Empire that spanned the world.

In England, they met. It was a moment of omnipresent, unashamed bigotry. When Akala’s mother met her boyfriend, she was disinherited by her family for being with a black man. Neighbors, meantime, spit in the street at her.

These were not just expressions; this bigotry was physically abusive, too. Like other black men of his generation, the traumatized body of Akala’s father told a narrative. The beatings at the hands of the Special Patrol Group, a famously violent police team, caused some marks. Battles with far-right skinheads were remembered by some.

Akala was dubbed “mixed race” in Britain. In Jamaica, he would have been named “high colored,” the word used to refer to the lighter skin tones of richer Black Jamaicans. Black was Black in the United Kingdom, however, and being Black made you a threat.

When he was initially persecuted racially, Akala was five. A friend probably borrowing from his parents what he had witnessed, called him the N-word. His mother found he was angry when Akala came back from school. She wondered what was wrong with him.

He proceeded to tell her about his friend, whom he referred to as a “white man.” Then he paused in his tracks. He knew for the first time that his mother was white. However, she was a fast thinker. “Yeah, I am white,” she said, “but I am not English, I am German.” This was not accurate; it was only when her military family was deployed there that she lived in Germany. But it was a safety valve that let Akala report racial violence without thinking that he was damaging the emotions of his mother.

Akala started to note the animosity went deeper than little boys tossing insults around school playgrounds towards persons who appeared like him. Later that year, a notorious occurrence during a soccer game was caught on tape. It displayed Liverpool winger John Barnes, born in Jamaica, throwing aside a banana skin that fans shouting racial slurs had hurled at him.

What did it mean by this photo? Akala recalls looking at the picture. He knew that this was important, but he hadn’t found out in what way yet.

Chapter 3 – Policing considers violence as a racist problem in London.

Teenage boys engage in a coming of age rite in many families around the world. These rituals signify their initiation into maturity, whether it’s a bar mitzvah or a weekend getaway.

Black teenage boys are experiencing another form of rite of passage in London’s worst boroughs: being arrested and questioned by the police.

Akala was 13 when he was searched for the first time. No parent was there and he had not been told of his rights. This is immoral as well as normal. Being questioned became a bi-monthly routine during the ensuing years. They were still looking for black boys; their white friends were not. The rule, Akala discovered, does not extend to all persons fairly.

The desire to eradicate juvenile knife violence also excuses this everyday invasion of civil rights. But it is not the effect it generates.

Read the paper in London and you’re bound to come away with two thoughts. First, London is overrun with “teenage thugs” knife-wielding. These young people have reportedly made the British capital one of the world’s most violent cities. Second, you might infer that these teens are predominantly black. Both myths are used to defend tough police and abusing black boys.

Let’s quickly clear one thing up. In London, street crime is a real concern and it concerns black teens. simply ask Akala. The same year that he was first arrested and searched, one of his friends was assaulted with a butcher knife by a black child. But here’s the thing: ethnicity isn’t the driving factor in teens’ criminal activity.

In Britain, let alone Europe or the world, London, the town where most Black British citizens live, does not have the largest percentage of teenage knife violence. In 2015, for instance, a nationwide report revealed that in predominantly white, northeastern English cities like Durham, the highest teenage knife crime levels were to be seen. Overall, Glasgow, which is once again overwhelmingly white, is the most violent Scottish city in the world. London, meanwhile, was ranked in the UK as the eighth-most aggressive.

Then what, if not ethnicity, ties places with high rates of teenage violent crime? Well, whether it’s the London district where Akala lived or nearly all-white neighborhoods in cities like Glasgow, there’s one common factor with these violent places: they’re all working-class and poor.

Chapter 4 – Black athletic achievements are also regarded as an unusual phenomenon.

Akala watched Dreaming of Ajax in 1995, a BBC film about the Ajax Amsterdam Dutch soccer team. Ajax, the weaker club, has for years controlled European soccer. It surpassed its wealthier English equivalents on a daily basis.

What did this overwhelming performance account for? The documentary pointed to the organization of the club: Ajax was better for running and had a better method of coaching than English clubs.

Quick forward to 2012, the year that London hosted the Summer Olympics. Another athletic discrepancy came under review by a separate BBC tribunal. The 100-meter dash was done in under ten seconds by only 82 athletes. They were nearly all black. This time, no one thought about the organization or coaching, however.

The background of the committee’s debate was straightforward: it was odd that there were no more white athletes winning. A small documentary sought to clarify this mysterious phenomenon.

It begins by outlining the notion of the survival of the fittest by Darwin. It then stated that top black athletes could track their origins back to enslaved Africans, including that year’s Jamaican gold medal winner, Usain Bolt. Since the ordeals of involuntary transport and slave labor survived just the fittest enslaved people, their heirs must have a hereditary genetic edge, like Bolt.

It’s pseudoscience. Studies suggest that the so-called ‘fast-twitch’ muscle is the secret to sprinting for both white and black athletes. Other reasons still exist, such as the money spent in athletics in, for instance, Jamaica. Then why has this hypothesis of genetics ever been put forward? One response is that white success is considered natural, while black success is considered an exception that needs an interesting explanation.

Consider a further case. After 1945, European soccer was governed by two nations – Germany and Italy. Why has it been? The standard answer is that both countries are crazy about soccer and have exceptional coaches.

But what happens if this uncontroversial perspective is not accepted? For more imaginative theories, you’d have to search. You might argue that Germany and Italy each had fascist regimes and lost the battle. Perhaps it has earned them unique genes for soccer!

This notion is crazy, and it’s hard to picture anyone on a BBC panel suggesting it. But the BBC was happy to consider an equally ridiculous explanation to justify the superior success of black athletes. This underscores a crucial point: the standard is now commonly regarded as white supremacy.

Chapter 5 – The role of Britain in abolishing slavery is not as straightforward as many say.

Britain marked the bicentenary of the Act of the Slave Trade in 2007. This 1807 legislative act banned slavery in the British Empire. Prime Minister Tony Blair shared his regret that Britain had engaged in the slave trade on the occasion. But he refused an official apology.

Many analysts agreed with Blair’s choice not to apologize. Britain was the first nation, after all, to eradicate slavery, they said. This was a rare success. A BBC documentary talked of a “spectacular” choice: Britain had stopped the slave trade and thus forgotten “massive income.”

This conception, which distorts much of the historical record, is fundamental to the national self-image of Britain.

In reality, Denmark was the first country to abolish slavery and it did so in 1792. When it outlawed slavery in its Caribbean colonies, revolutionary France followed two years later.

This involved Haiti, or Saint-Domingue, as it was known at the time then. It was one of the most successful colonies worldwide. Half the world’s coffee and as much sugar as Brazil, Cuba, and Jamaica together, were created by the enslaved people living there.

The response from Britain was to send troops to Saint-Domingue. They aimed to conquer the colonies and return slavery to British control. The scheme was disrupted by freed slaves serving under the French flag. Around 50,000 British troops died.

In the final, the post-revolutionary leader of France, Napoleon, wanted to re-establish slavery himself. Domingues outraged. They beat back a murderous French campaign and founded the first free Black Republic in the world in 1804: Haiti. It is the last country to end slavery in history. Britain has now declined to acknowledge this new government, having backed France’s effort to destroy the Black Republic.

Britain kept working with slave-owning cultures long after abolishing slavery. It exchanged and invested comfortably in the southern slave states of the US as well as Cuba and Brazil. Slavery was not abolished until 1865, 1886, and 1888, respectively, in those areas.

And not exactly did British slave merchants risk their money, either. In reality, before 2008, they earned the biggest public bailout in British history with the Slave Trade Act. Just 182 years later did the British state finish paying back the debt.

Chapter 6 – Public perceptions do not match how many Black Britons recall history.

There are two facets of history: truth-stuff that happened, and interpretation – the significance we assign to certain facts. Interpretation, however, is not just what historians do. It’s a mechanism for the people.

In Akala’s youth in Britain, there were few black representatives in politics. that condition is improving. In public life, black Britons play a growing part. Often the country is demographically evolving. About 30% of the British people will have African, Asian, or Caribbean origins by 2050. How is this going to influence the discussion about the history of the country?

Well, the history of colonization in Britain is now being re-evaluated. In the latest efforts to destroy monuments honoring white supremacists and slave owners, you can recognize that. But more current occurrences will still have to be reconsidered.

Take the official story about two legendary figures of the 20th century: Nelson Mandela of South Africa and Fidel Castro of Cuba.

He was appropriately named a “hero” by the British government and media when Mandela died in 2013. By comparison, when Castro died in 2016, even the independent Guardian newspaper told people to “forget the actions of Castro.” All that counted, the newspaper claimed, was that Castro “was a tyrant.”

There is something wrong with these myths for Black Britons of Akala’s generation. They elude Britain’s global involvement in bigotry.

For instance, back in the 1980s, the British government did not name Mandela a “hero.” Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher named Mandela the head of what she called a “classic terrorist group.” When they launched a “hang Mandela” movement, she declined to censure activists from the youth organization of her party. Britain proceeded to give its financial and political assistance as other countries boycotted South Africa.

And as for Castro, a historical overlooked spot is also revealed by Britain’s inability to consider his good hand.

In 1975, to protect its transitional government from the South African invasion, Castro’s Cuba sent 36,000 soldiers to Angola. In 1988, these troops joined forces at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale with Namibian and Angolan freedom fighters to beat the South African military.

Mandela stated on a visit to Cuba that this triumph had shattered what he termed “the illusion of the white oppressors’ indestructibility.” It wasn’t just a rhetorical crushing blow against segregation. The talks that followed the war led directly to Mandela’s release from jail and his group, the ANC, being legalized.

At least Mandela didn’t think we could neglect the policies of Castro and Cuba.

Chapter 7 – In different areas, anti-Black bigotry takes different shapes.

White people also reject the reality of “white supremacy.” Regardless of their skin color, there are the systemic privileges that white people enjoy. The nature of this advantage, however, is evident from the viewpoint of a “mixed-race” person such as Akala: various cultures perceive him differently depending on how they view his blackness.

As we have noticed, an individual of his race in Britain is seen as literally a black person. He is considered as “colored” in South Africa, by contrast. This compares again with nations like Algeria that are North African. Black people are also routinely referred to there as abeed, in Arabic, meaning “slave.” Akala is not though, an Abeed. He leaves for the nearby brown-skinned Amazigh.

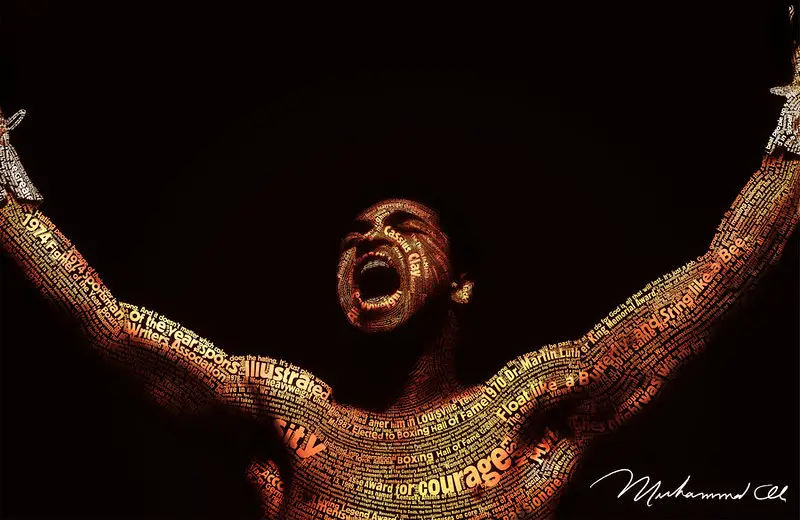

For one, many Black American progressive heroes were lighter-skinned. In the Caribbean, figures like Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, and Huey P. Newton, part of the lighter-skinned Black class, will be seen as “uptown people.”

They were classified as black in the United States, though. The designation was a result of the so-called “one-drop law,” which claimed that Black was, constitutionally and socially, anybody with a single Black ancestor.

Body-color, then, means various things in various cultures.

He encountered many people who appeared white when Akala toured Australia but referred to themselves as “blackfellas.” This word is used by many Aboriginal people to refer to themselves. This represents their memories with particularly harsh anti-Black bigotry.

We have to consider the past of how the Australian government handled Aboriginal people to understand how individuals of a “fair” complexion came to be known as black.

Approximately one in three Aboriginal kids were forcefully separated from their parents between 1910 and 1970. Then they were adopted either by white families or in the children’s homes. Any scholars think that this strategy is considered an act of genocide. That’s how it was trying to crack the bonds between these kids and their conventional culture and identity. Their “assimilation” into white Australian society was the aim.

Not “assimilation” was the consequence, but generational damage. The children were told that they had been willingly rejected by their mothers. Most of the kids were undereducated and exposed to dreadful physical and sexual assault. Combined, they are recognized as the’ stolen generation.’ One of the legacies of this colonial approach is the’ white-looking’ Aboriginal people Akala met in Australia.

Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire by Akala Book Review

As equal subjects of the British empire, the Caribbeans came to the “motherland.” A surge of racial animosity reached them. Early on a kid of this age, Akala discovered that being Black in Britain means being a resident of the second class. He was exposed to racialized policing as a youth and told convenient lies about the less than glorious history in Britain. So it’s making changes. In public life now, black Britons are more common than they were in the past. The way the country sees itself and its past, that’s going to change.

Try Audible and Get Two Free Audiobooks

Download Pdf

https://goodbooksummary.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/Natives+by+Akala+Book+Summary+-+Review.pdf

Download Epub

https://goodbooksummary.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/Natives+by+Akala+Book+Summary+-+Review.epub