The United States was afflicted at the beginning of 1861 by discord, hostility, and uncertainty. Northern states, such as Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, and Southern states, such as Georgia and South Carolina, were never more distinct – geographically, culturally, and politically. At the heart of the schism was the plight of more than three million enslaved people who at the time were living in the South. Their labor maintained the Southern way of life dedicated to preserving the aristocratic planter class. The civil war hurricane was growing, and it would kill more Americans than all the wars from the American Revolution to World War II together when it inevitably broke.

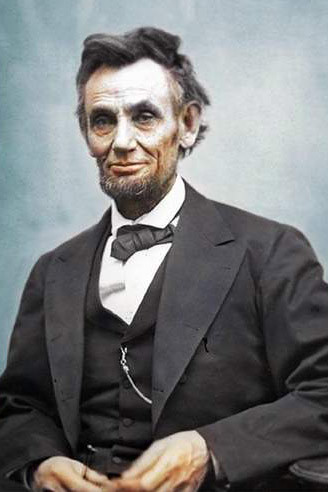

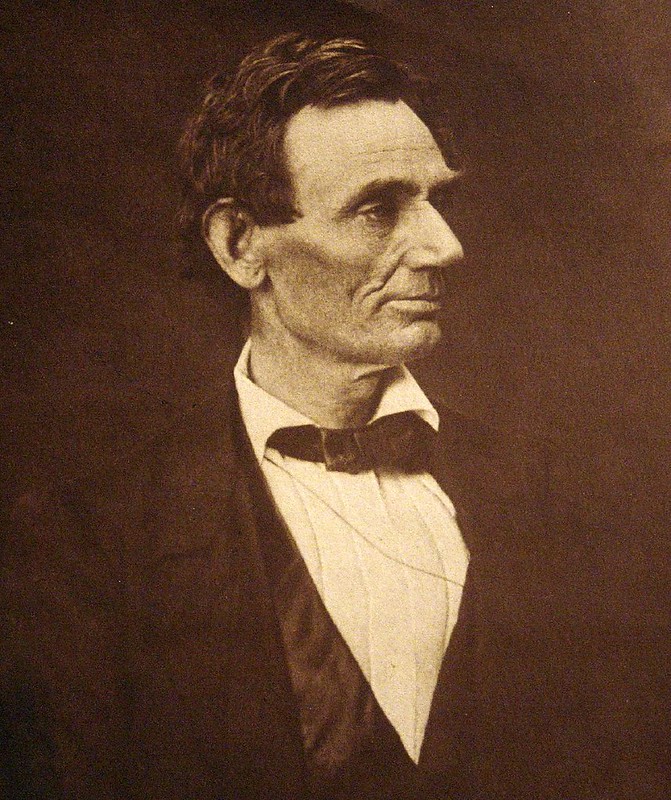

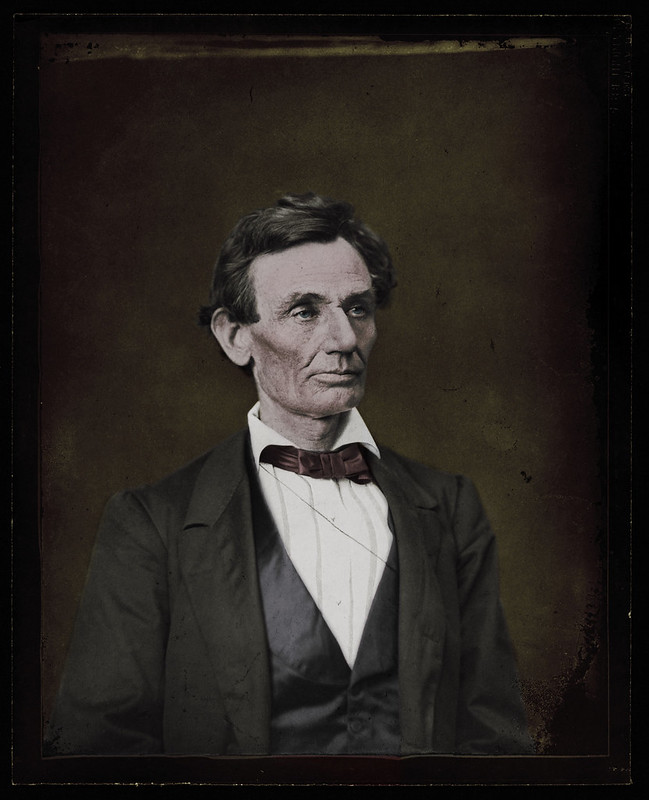

A cause for the schism of the United States was the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860. Lincoln, a blatant abolitionist, was despised widely in the South. Southern officials, company scientists, and representatives of clandestine, armed groups that finally gave rise to the Ku Klux Klan, promised to die seeking to keep Lincoln from coming to power.

On his way to his inauguration in Washington, D.C., Lincoln will have to travel through the rabidly secessionist city of Baltimore. This would be their greatest hope for those who meant Lincoln harm.

Chapter 1 – Abraham Lincoln established himself as a convincing orator in the debates with Douglas – and an abolitionist.

It was summer dog days, August 1858, and tourists were crammed into the town of Ottawa, Illinois. For days, thousands of people had poured in, from all over the state. Here, Ottawa was hosting more than double the normal population on the day everybody had been waiting for.

The atmosphere was cheerful, but it wasn’t a county fair: it was a democratic dispute between two U.S. Senate candidates from Illinois.

Stephen Douglas was highly expected to win. A rich landowner, slave owner, and insider from Washington, Douglas has previously served in the Senate for two terms. His rival was an upstart Kentucky lawyer whose name awareness was so bad that he was still named as Abram Lincoln by the media.

The two opponents were not merely different in terms of historical background. They appeared, almost to the point of comedy, like physical opposites. Douglas was stumpy and tiny, with fat cheeks. Lincoln was tall, a foot taller than Douglas, with a body dubbed gawky by the press, and a face strikingly triangular.

Their policies were also in stiff opposition, especially on the question of slavery, the day’s hot-button topic. Douglas was a strong promoter of pro-slavery and a lifelong white nationalist. “I don’t think the negro as my equivalent,” he said. “He belongs to a lesser caste, and must therefore take a lower role.”

For his part, Lincoln used folksy charm to win over the audience. And on the topic of slavery did he become animated. “I can not help dislike the passion for the propagation of slavery,” he said. “Due to the monstrous cruelty of slavery itself, I hate it.”

Illinois was a swing state and the arguments between Lincoln and Douglas were closely monitored. Lincoln lost the race, but it was commonly recognized that he had almost unseated the incumbent. As an abolitionist and articulate orator, Lincoln’s star was rising.

Two years later, in 1860, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois State Republican Convention as the Republican presidential candidate for Illinois. He had been so famous that he had to practically surf the stage crowd. In the end, he rode the tide to become the candidate of the national Republican party. Lincoln was campaigning for the presidency.

But the headlines in New York still had his name mixed up.

Chapter 2 – Constitutional instability in the South helped to bring on what was a terrifying scenario for many: President-elect Lincoln.

The reaction to Lincoln’s appointment has been strong in the South. As word circulated that the Republican presidential candidate was a Northern activist, a group of men assembled in a hair salon in Baltimore run by Cypriano Ferrandini, a Corsican refugee who had sought an intellectual refuge in the progressive Southern politics. Ferrandini’s barbershop became a gathering place for the wealthy white supremacists of Baltimore. It was the final straw for them, as it was for those in the South.

There was increasing enthusiasm in the North for the abolishment of slavery. Increasingly the Southern planter class thought their way of life, which relied on slave labor, was under threat by a government that no longer served them. The abuse was on the rise, even at the centers of authority in Washington. In 1856, a South Carolina representative pounded an abolitionist Massachusetts senator nearly to death on the floor of the US Congress.

Participation had grown in the Knights of the Golden Shield, a clandestine organization committed to defending white Southern interests, by intimidation if required, in the years leading up to the 1860 election. The knights were equipped at all moments, like Ferrandini and his allies, with loaded revolvers and Bowie knives. The company had an estimated 40,000 participants by 1860.

But the Southerners were not just militant secessionists. At the moment, between secessionists and the mainstream Democrats, the National party was divided. The National Democratic Convention of 1860 showed just how divided the party was on the secession issue. The debates were not only exceptionally aggressive but were often accompanied by fistfights. A solution was, eventually, unlikely. The convention divided and offered two opposing presidential candidates.

Lincoln was expected to win the election with no united resistance. This was dubbed a dystopian situation in the South. The president may, for the first time, significantly challenge the practice of slavery. In Southern papers, the language of rebellion has been progressively used: “we must not submit,” the Montgomery Weekly Mail of Alabama stated.

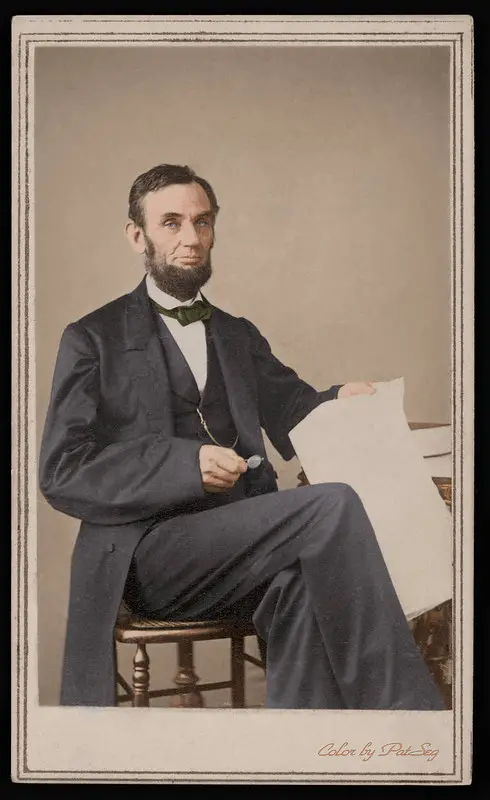

Lincoln remained up all night on Election Day, November 6, measuring percentages for each state and watching the findings coming in. rHe won comfortably, and spent the night cheering and thanking backers.

He’d actually been alone by 3:00 a.m. Haunted by a strong feeling of foreboding, he was not able to relax. In a darkened room, gazing up from his chair, he caught sight of himself in the mirror. He’s seen a ghostly dual vision of his profile there, with a start.

In the coming weeks, he and his wife were infinitely brooding over the illusion. They agreed, eventually, that the omen was not a positive one. It meant death inopportune.

Chapter 3 – The South reacted to his victory in troubling ways as Lincoln prepared to take the presidency.

Lincoln had claimed during the presidential race that he had no plan of abolishing slavery where it had existed. He would only discourage new US territories from introducing slavery. Nevertheless, his victory was perceived by Southerners as a kind of catastrophe. To them, the increasing disunity between themselves and the North calcified it. The North had voted Lincoln as President, not the South.

Southerners, both personally and in masse, didn’t wait to act.

Lincoln quickly started collecting about 70 letters a day. Not all had been well-wishers. A startling number of threats of death and rambling declarations of everlasting hate, as many as a dozen every day, have occurred. One said, “Old Abe Lincoln, God damn your god damned old Hellfire god damned soul to hell…” and so on. One threatened to “put an insect in your dumpling ”

It was not just crazy people who intensely responded to Lincoln’s election. The state assembly of South Carolina carried through in December with a threat it had made only three days after the election: it voted to separate from the United States. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, and Georgia followed South Carolina shortly after.

The South was full of jubilation. The North was fascinated. The election of Lincoln was the cause for separation, so now everyone turned to him for a response. However, the president-elect was supposed to stay silent in those days until he started his term, as a sign of support for the outgoing office. Lincoln kept quiet except for certain letters to party officials, which highlighted his intense dislike of slavery.

He and his recently recruited colleagues had plenty of daily duties to take care of anyway. Not only did he have a new career to train for, but he had to plan a cross-country transfer. What’s more, he was now the country’s most popular and pursued-after man.

He would give the citizens what they asked for: a promotional trip from Springfield, Illinois to Washington, D.C. That would be a challenging ride, tickets for numerous transport firms and geographic parts, timed visits and meetings with local officials. Not to mention bookings for overnight stays and a safe transfer of bags. There would be enough potential for anything to go wrong with too many moveable pieces.

One thing concerned Lincoln’s security staff most: the final leg of the trip will carry the President-elect far into dangerous territories.

Chapter 4 – Apparently, threats were everywhere. Fortunately, Felton invited the one guy who could tie the dots.

Rumors started circulating in Washington. Whispers of underground societies were bent on stopping Lincoln from taking office and even a Southern militia rebellion, supported by hidden spies, already in the capital. Squished between Virginia and Maryland, both slave states, the city was in a vulnerable position. If a Southern militia were to strike, Government assistance would be shut off.

There were also reports coming to the north, to railroad magnate Samuel Felton’s office in Philadelphia. Word got to him that a shadowy cabal was trying to blow up his train lines between Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington to discourage Lincoln from entering the capital.

Even more worrying, George Kane, the Baltimore Police Marshal, casually ignored him when Felton reached out to him about what he had heard. It was not forgotten for Felton that Kane was an avowed secessionist.

Felton knew just the guy for the role, someone who in the past had got him out of a problem. He sent an urgent message to Allan Pinkerton in Chicago on January 19th.

Pinkerton was the first private investigator in America, a leader in the field. He was bright, imaginative, and not easily inclined to give up. Specializing in the bank robbery and counterfeit activities, he had taken down some of Chicago’s most notorious crooks. He had already made several friends and had survived at least one attempt at assassination.

By the time Felton’s message reached him, Pinkerton was in control of a booming project on his payroll, with thousands of employees. The first female investigator in the US, Kate Warne, was one of them.

Pinkerton was a man with fierce values as well. He was a passionate abolitionist, and admirer of Lincoln, the hometown hero of Illinois. His house in Chicago was a well-visited destination for people escaping poverty, moving to Canada.

Startled by a letter from Felton, Pinkerton hastened to Philadelphia. He came to a much more disturbing conclusion after speaking with the railroad magnate. The stories of violent secessionists, white supremacists’ underground government cabals, and railroad saboteurs were frightening enough. But now, the president-elect has made his promotional tour schedule official. Those who wished him harm will, according to the scheduled timetable, have the chance to do so at home in the South.

Worst of all, Pinkerton had just a few days to formulate a plan to preserve America’s greatest chance of ever bringing an end to slavery.

Chapter 5 – Pinkerton’s investigators went undercover in Baltimore, to uncover – and to prevent – any scheme against the elected president.

A few days later Pinkerton, alongside his best officers, was making his way to Baltimore. They had just a few days to train, to practice their Southern accents, to establish false identities, and to acquire accessories for their camouflage. Their strategy was surprisingly bold: to penetrate, discover their intentions, and thwart the gangs of white nationalist secessionists in Baltimore, making sure that Lincoln made it to his inauguration.

They encountered a city seething with rage, self-righteousness, and animosity toward one goal when they entered Baltimore: Lincoln. Pinkerton felt it wouldn’t take long before there was an active rebellion.

Pinkerton adopted his new name on February 11th. Now it was John Hutcheson, an investment banker from Alabama. The Hutcheson office locale was no mistake. The offices of Thomas Luckett, a stockbroker, and a professed secessionist, were in the same building.

The other agents of Pinkerton were also making their appearances in the Baltimore community of white supremacism. Harry Davies was a beautiful young man with a gentlemanly New Orleans accent that fitted him well for the job. Otis Hillard, a not-too-bright socialite from Baltimore, was his label. Davies discovered after many hours of carousing in pubs, clubs, and brothels that after he had a few beers, Hillard talked more openly.

Hillard had speculated at a large-scale intervention expected against Lincoln, but for Hillard to be persuaded of Davies’ devotion to the cause it took a few more raucous evenings peppered with pro-secessionist slogans. Hillard finally took Davies to the barbershop of Cypriano Ferrandini, a home base for rich white supremacy in Baltimore, to meet the plot’s author. But they had just missed him.

Pinkerton had, meanwhile, been trying to ingratiate himself with Thomas Luckett, insulting Lincoln fiercely. Luckett was extremely furious on February 14, outraged by the flattering attention Lincoln was receiving in the Northern press. He disclosed his participation in a large enough organization to challenge Lincoln and their underground stockpiles of arms and ammunition. Sensing an opening, as a donation, Pinkerton handed Luckett the equivalent of $750 into today’s currency. Thrilled, that very evening Luckett proposed to introduce Pinkerton to the head of the organization.

It was Ferrandini, the barber. While drinking, Ferrandini became extremely irritated – and persuasive. He stated, “murder of any sort is reasonable and correct to save Southern people’s rights.” Pinkerton had a startling realization: right there in Baltimore, Ferrandini was trying to kill Lincoln.

Chapter 6 – As Lincoln launched his promotional tour, his fame – and the threats to safety – revealed to be higher than expected.

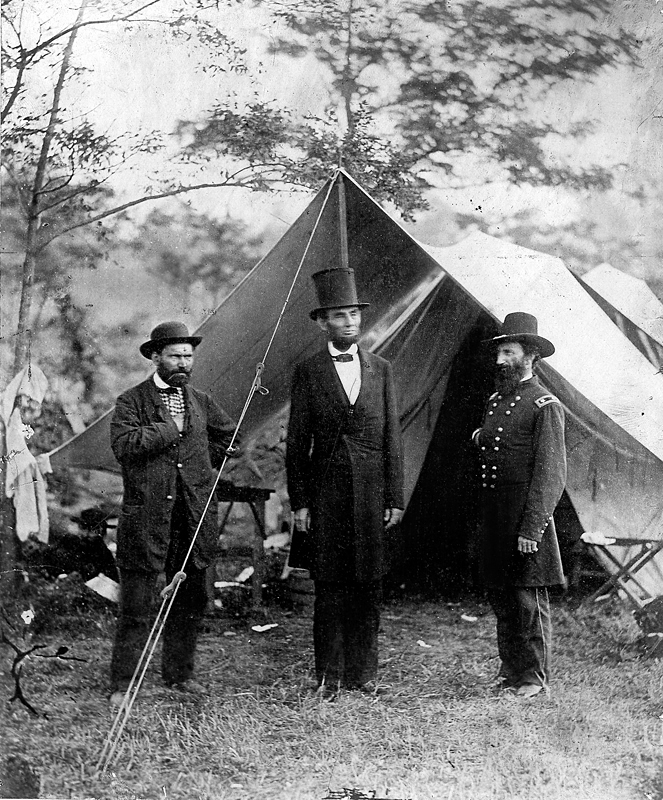

On February 11, 1861, Lincoln’s caravan left Springfield. Lincoln embarked without a military escort, against the recommendation of friends concerned about the alarming, recurring rumors. He did, however, have a few security guards, meaty pub scrappers, and professional soldiers who know how to handle themselves.

Crowds gathered at every station to root on the president-elect’s train. Lincoln was ready for a quick grin and a folksy laugh at any gate. The crowds got even bigger as the news of Lincoln’s charming way spread. The organizers for the trip had evidently understated the interest of the public in the gangly man who was about to become their president.

The biggest city yet on their tour was Cincinnati, Ohio. The crowd was enormous and the Lincolns were mobbed by well-wishers on the way from the station to their hotel. Lincoln, the truth is, was prone to attacks. Everybody could take a shot during his addresses, meet and greets, or meals.

As Lincoln was staying at his Cincinnati hotel for the night, a stranger who wouldn’t take no for an answer turned up at the front desk. He asked to see Norman Judd, a member of the elected president’s party. The courier had just arrived from Chicago to deliver Pinkerton’s letter by hand. Pinkerton recognized Judd from Chicago; he knew that Judd could be trusted with the provocative details found in the letter: that there was a scheme on Lincoln’s life.

Judd was hesitating. There had been a lot of threats already, he argued. Why is this one any distinct? He sent a letter in Baltimore to Pinkerton telling the detective to keep him constantly aware of the case. He would be alert but would not be taking any extra measures.

But the promotional tour for Lincoln was about to become even more wild and volatile.

On February 16, as the train was pulling into Buffalo, New York station, there was uproar. The crowd seemed unmanageable as former President Millard Fillmore stepped forward to welcome Lincoln. The security team for Lincoln was exhausted. One of the bodyguards in Lincoln displaced his shoulder. The strain on members of the audience led others to pass out. Lincoln himself was crushed but unharmed.

The danger seemed to be rising by the day, and they were still in a loyal anti-slavery Republican nation.

Lincoln, however, had been expected to drive into Baltimore in just seven days. Neither he nor his staff has any clue what’s in store there for him.

Chapter 7 – Pinkerton persuaded his security unit of the threat with just days to go before Lincoln went through Baltimore.

The persistent stranger at the Cincinnati hotel in Lincoln wasn’t the only special agent for Pinkerton. Warne, on a train from Baltimore to New York, was speeding into the darkness. Pinkerton had trusted her with another important news for Norman Judd.

Until the job was completed, they would have code names. Lincoln’s was slightly unfitting for a guy destined for the country’s highest office. The president-elect may from then on be called Nuts.

When Judd arrived in New York, he found himself facing a continuous sequence of surprises. Firstly, it was a lady the agent Pinkerton appointed to contact him. Moreover, she held a letter with even more proof of a conspiracy against the life of Lincoln to be executed in Baltimore City on February 23. Ultimately, the stubborn woman had the dare to deny as Judd demanded more information.

Warne invited Judd to come to Philadelphia to visit Felton the railroad scion and Pinkerton himself. They would inform each other in detail, then collectively create an action plan. Following this meeting on 21 February, Judd was eventually persuaded of the risk of informing his employer.

But how can they achieve the mission of getting Lincoln to Washington from Philadelphia without traveling through Baltimore? They wouldn’t. Pinkerton’s idea was to sneak Lincoln on an overnight train through Baltimore before the scheduled timetable, going through the city before anybody realized he’d been there.

Finally, it was time to inform Lincoln of the conspiracy against him. After a lot of wrangling with crowds and agents, they actually sat down in a hotel room with Lincoln. Lincoln did not utter a word when Judd and Pinkerton laid down the crazy chain of incidents that had taken them there, the furious atmosphere in Baltimore, and the attitude of the secessionists he had met. Pinkerton finished by announcing that there would be an attempt on his life in Baltimore if the arrangements weren’t updated.

Pinkerton said, if they hurried right now, they might catch the late train to Washington.

Lincoln declined, after a moment. The following day, he will complete his responsibilities and then go along with whatever they considered necessary.

Chapter 8 – As opponents of Lincoln formulated their plans, Pinkerton, Warne, and Lincoln embarked on a hopeless overnight flight.

In the meantime, Harry Davies had been called back in Baltimore to a gathering of the underground party plotting against Lincoln. He was sworn in by Ferrandini in a complex ceremony, dressed all in black, who set out the plan: to kill Lincoln, on Saturday, February 23, soon after 1:00 p.m., when the president-elect switched between Baltimore’s train stations. This left less than three days for taking action.

George Kane, the Police Marshal of Baltimore, was on the scheme. He’d make sure that Lincoln didn’t have an appropriate police escort.

The gathering aimed to decide who would ultimately deliver the fatal shot among them. They’d draw ballots and the work would be up to whoever got the red one. Until after a shot was fired, the name of who had drawn the red ballot will not be exposed.

Warne and Pinkerton were in Philadelphia, making plans last minute for a hidden, risky trip. It wouldn’t be easy to preserve privacy. Lincoln was extremely tall and his profile was notably iconic. The trip is on public trains, where everyone can see him. They will have to keep his secret in four big cities, three main tracks, six train stations, and a few wagons.

The project to decide the destiny of a country was initiated on 22 February at 6:00 p.m. Dressed up in a fluffy felt cap instead of his regular classic top hat, Lincoln embarked a privately chartered train from Harrisburg to Philadelphia, joined only by Judd and a hefty security guard. Warne and Pinkerton met the party in Philadelphia where Warne had reserved a public sleeper passage for him. On the passenger list, Lincoln was identified as Warne’s illegitimate brother.

Lincoln’s wagon pulled along a darkened side street up to the Philadelphia station. Pinkerton and Lincoln went to the train easily, entered through the rear entrance, and came across Warne. Each collapsed into their seat for an unpleasant night after putting their ‘illegitimate brother’ into the sleeper cabin.

They rolled into Baltimore, the City of Rivals, at about 3:30 a.m. As station workers removed the motor from the carriage and tied it to horses that would drive it to the other station in Baltimore, Lincoln and his attendants sat quietly. This was the most fragile moment. The group would travel through Ferrandini’s barbershop within four miles.

They managed to make it to the other station and waited as the staff was connecting the carriage to the Washington train. It took off at around 4:30 a.m. Ferrandini was too late, along with his plotters.

Chapter 9 – The scheme was disrupted, but Lincoln had only suffering ahead of him – and eternal posthumous fame.

As Lincoln and Pinkerton came to Washington, they had not slept for nearly 48 hours either. But the task has still not been over. Pinkerton also wanted to mask the presence of Lincoln as they found their way through the station in Washington. He failed: a middle-aged man leaped up, caught Lincoln, and yelled his name. Pinkerton made a move.

“Don’t touch him! No! That’s my mate,” shouted Lincoln. Pinkerton released the man’s lapels nervously. Lincoln has laughed and introduced him to his longtime friend, an Illinois representative.

The three of them were in a carriage bound for a hotel where Lincoln was able to get some rest. Pinkerton was beginning to relax too. Lincoln’s health was not his duty for the first time in as long as he could recall. The covert scheme was disrupted and the president-elect was secure.

It became the main topic of conversation as rumors filtered through the city that Lincoln had been smuggled into Washington to escape an assassination attempt in Baltimore. The press had a pleasant day: Lincoln was caricatured and accused of timidity, unlike a president. However, the controversy over Lincoln’s path will quickly be replaced by other incidents.

Thirty-nine days after Lincoln was sworn into office as president, the Confederate Army opened fire on South Carolina’s Fort Sumter, a Union stronghold, on April 12. These were the first bullets that were fired during the civil war.

Death will torment Lincoln during his time as president. Ultimately, under Lincoln’s administration, more Americans died than were killed in any other battle, from the American Revolution to WWII combined. And his young son Willie died while in government.

Some elements of the Baltimore Plot remain veiled in secrecy to this day. None of the conspirators have ever been identified for sure. While several of the suspected plotters had been active with the Golden Circle Knights, they presumably behaved outside of the formal organization.

The Golden Circle Knights stayed active in the 1860s. In the Confederate Army, several participants enlisted. Many prominent individuals, including a young actor named John Wilkes Booth, find their own means of promoting their white nationalist, secessionist message. Booth shot Lincoln in the head at Ford’s Theatre in Washington on April 15, 1865, killing him.

But even with his ill-timed death, what Lincoln did during his presidency profoundly changed the country. Had the Baltimore Plot worked, the Emancipation Proclamation may never have been issued by Lincoln, perhaps the most controversial and far-reaching revolutionary document since the Declaration of Independence. About three million enslaved people in the US were liberated in a pen instant on January 1, 1863.

The Lincoln Conspiracy: The Secret Plot to Kill America’s 16th President—and Why It Failed by Brad Meltzer, Josh Mensch Book Review

Southern secessionists swore to stop at nothing in the intense days leading up to Lincoln’s first inauguration to stop him from coming to power, rebellion, or not. A disparate group of participants foiled the assassination attempt only by teamwork, chance, and a professionally polished collection of convincing Southern accents. By doing so, they paved the way for the abolishment of slavery, the most major political movement in America since the Declaration of Independence.