For people who stay in modern industrialized societies, the mosquito is typically an irritating small insect that destroys our enjoyment of the great outdoors. However, in the whole of human history, and in huge swathes of the world till now, it’s been the human lethal enemy.

The death rate is overwhelming. From the 108 billion people who have ever lived in the previous 200,000 years, approximately 52 billion of those people died as a result of mosquito-borne diseases. Also, in 2018 only, those diseases caused the deaths of 830,000 people with the majority of those people living in Africa and Southeast Asia.

However, those statistics start to describe the story of the mosquito’s terrific effect on human lives. From ancient eras to now, and from the grand-scale geopolitics of great civilizations to the constituent of people’s DNA, the mosquito has transformed the human history at various serious points, and in a range of dramatic means.

1 – Flourishing in wet warm environments, mosquitos are vectors for different diseases in which the deadliest is malaria.

Before we go deeper into the history of humanity, let’s begin with a step back and get to know about the story of our enemy which is the mosquito itself.

Or relatively, the mosquito herself. It’s just the female mosquito that bites humans and sucks up their blood, – possibly transmitting diseases during that process. The mosquito makes use of this blood to grow her eggs. A few days after she bits us, she’ll lay up to 200 eggs on the surface of stagnant water. This stagnant water could be a pond, a swamp, a puddle or a small pool of rainwater in a thrown away beer can. She doesn’t require a lot to work with. With that being said, the wetter the surroundings, the more it’ll function as a breeding place for the mosquito.

Also, temperature serves as an important part of the thriving of mosquitos. They like temperatures more than 75 degrees Fahrenheit, while they cannot endure in temperatures lower than 50 or more 105. Due to that, in temperate climates, they only appear during spring, summer, and fall, whereas in tropical climates, they are always active.

Therefore, warm wet surrounds offer the perfect environment for mosquitoes and the diseases they cause. These diseases are produced by pathogens that make use of the mosquito as vectors and that is the organisms they transmit themselves. There is a minimum of 15 mosquito-borne diseases that disturb our species, and they come from three kinds of pathogens which are viruses, worms, and parasites. They comprise of the worms that lead to elephantiasis, which causes dangerous swelling of the limbs and the other part of the body, as well as the viruses that lead to dengue, Zika, West Nile and yellow fever.

In history, the greatest hitter is the parasite that leads to malaria. We have five kinds of malaria that affect human beings in which the most lethal are vivax and falciparum. These have the ability to lead to a 106-degree Fahrenheit fever, seizures, and comas that can cause death rates of up to 50%. Malaria started affecting our prehuman ancestors about six to eight million years ago, and since then, it’s been affecting us.

As it goes hither and thither between humans and mosquitos, the malaria parasite transforms different times during its multi-stage reproductive cycle. This is a result of its continuous shape-fluctuation which makes it difficult for scientists to isolate the parasite and create an effective vaccine. However, that has not hindered human beings from combating it, in a war that goes way back to thousands of years.

2 – Sickle cell feature developed as genetic protection against malaria and had extensive historical consequences.

Human beings have developed various genetic defenses against malaria –a lot of them with weird-sounding names, such as Duffy negativity, thalassemia, and favism. However, these defenses have been combined with blessings, which have regularly seemed more like curses to their beneficiaries. One of the greatest famous instances offers a case in point and that is the sickle cell trait – also called the sickle cell anemia.

The history of this trait starts in the last 8,000 years when the agricultural Bantu-speaking people of West Central Africa began living along the Niger River delta. The region was perfect for growing yams and plantains. Unluckily, it was also a house to swarms of malaria-infected mosquitos. The disease destroyed the inhabitants who couldn’t fight it.

However, they grew a genetic mutation that showed to be a huge change. The mutation made the hemoglobin in the blood to be formed like a sickle shape, instead of an oval or donut shape, like it usually is. The malaria parasite couldn’t join itself to this new form of hemoglobin, disturbing its reproduction cycle. The outcome was: people with the sickle-cell trait formed close to 90% immunity against malaria.

Also, unluckily, they formed an average life expectancy of just 23 years. However, that was enough time for them to reproduce and transmit the sickle cell trait to their offspring, which enabled their children to be more likely able to withstand long enough to reproduce themselves.

When the Bantu-speaking people began moving to the south and east across Africa between 5,000 and 1,000 BCE, their immunity to malaria provided them an important advantage against the groups of malaria-provoked hunter-gatherers they faced on their way. Those groups involved the Khoisan people, who took shelter in the Cape of Good Hope, on the southern coast of the continent. Few of ethnicities within the Bantu linguistic group went further to grow more dominant inland societies such as those of the Xhosa, Shona, and Zulu.

Moving to the 1652 CE, when the Dutch began to colonize some regions of southern Africa. With only a bit of Khoisan people living on the coast, it was very easy for the Dutch to take over that land. However, when they, and later the British, attempted to enlarge inland, they faced the strong Xhosa and Zulu people – together with swarms of malarial mosquitos, which affected their soldiers.

However, this was just the first time the mosquito had sent extensive ripples across human history.

3 – Mosquito-borne malaria had a huge impact on both the wars of the Greco-Persian and the Peloponnesian.

Let’s leave southern Africa and move to the beginning of Western civilization. We’ll start in the fifth century BCE when there were two competing superpowers fighting for supremacy over the Mediterranean world and that is the Persian Empire and Greece.

During that time, Greece was separated into rival city-states, which were controlled by two coalitions – one was controlled by Sparta and the other one was controlled by Athens. From 499 to 449 BCE which was the Greco-Persian Wars of, these alliances joined against the attacking Persian Empire, however, even with their united military forces, they were greatly outstripped by their powerful Persian opponents.

It seemed like the burgeoning Greek civilization might be grabbed in the bud before a lot of its history-changing inventions in science, mathematics, philosophy, and art had an opportunity to happen.

However, Athens and Sparta were saved by a third associate: the mosquito. As the Persians attacked Greece and surrounded the Greek towns, they had to go through and at times settle close to the mosquito-filled swamps. A deadly mixture of malaria and dysentery caused the death of about 40% of the Persian forces. Due to that, at the climactic Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE, the Persians got there with an extremely weakened army, which the Greeks were capable to conquer – successfully ending the Persian attack of Greece.

Then, Athens and Sparta eventually turned on each other during the Peloponnesian Wars of 460 to 404 BCE. Once again, the mosquito had an important impact on determining the consequence of vital occasions. In 430 BCE, the Athenians were on the edge of success when a dreadful disease affected their city, killing close to 100,000 peoples and that is 35% of its population. What was the cause? Possibly malaria or a mosquito-borne disease related to yellow fever.

Later, the mosquito would save the Spartans’ once again. In 415 BCE, the Athenians started a two-year blockade of Syracuse, which was a supporter of Sparta. That also was filled with mosquito swamps. By 413 BCE, close to 70% of Athens’ and 40,000 soldiers were either dead or weak to fight as a result of malaria. The people that didn’t die were eventually killed, taken or sold into slavery by their opponents.

The mosquito-led conquest at Syracuse sent the Athenians into a plunge from which they never got well again – eventually submitting to the Spartans in 404 BCE. However, it was a hollow success, as we’ll get to know in the following chapter.

4 – Malaria led to the downfall of Alexander the Great.

During the time the Spartans defeated the Peloponnesian War in 404 BCE, the majority of southern Greece were destroyed. The damage caused by the war was further intensified by malaria-endemic, which weakened the population of Greece and caused farms, mines, and ports not being attended to.

With southern Greece in ruins, a fairly unharmed and isolated kingdom was able to arise and be in power. The name of the place was Macedon, and it was ultimately controlled by a man who was called Alexander the Great.

By 326 BCE, the popular Macedonian leader appeared to be impossible to stop. First, through a combination of war and diplomacy, he united the majority of Greece, except the very weakened and disregarded Sparta. Afterward, Alexander and his forces went east and defeated the Persian Empire and the huge regions of central Asia. The subsequent region of this empire involved more of modern-day Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel/Palestine, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan.

Now Alexander’s had eyes on India and Pakistan. However, before going into the wet and warm areas of the Indus River Valley, Alexander’s army encountered its strongest rival. You predicted it – the mosquito.

Already strained thin as a result of years of fighting, overstrained supply lines and growing confidence on mercenary soldiers, Alexander’s army couldn’t survive the malaria plagues that ripped through its ranks as it went past the valley’s mosquito-filled swamps and rivers. They eventually withdrew back to their empire’s area.

During the withdrawal, Alexander gad a brief stop in Babylon, where he needed to reorganize and strategize his next invasions –however, that never happened. In 323 BCE, Alexander the Great unexpectedly died of sickness at the age of 32 –probably as a result of malaria. One of the greatest defeaters in world history seems to have been conquered, again, by an insect that has nearly equal size and weight as grape seed.

The outcomes were huge. Before his death, Alexander was planning an attack on the Far East. If that attack was successful, that would have been the first time where the East and the West would have been directly connected, 1,500 years before European traders such as Marco Polo forged a connection. In its place, immediately after his early death, Alexander’s mighty empire started to fall as his generals began fighting one other.

We will get to know that, that was definitely not the final time the mosquito would have a huge part to take in determining the fate of an empire.

5 – Malaria was a significant influence on the rise and destruction of the Roman Empire.

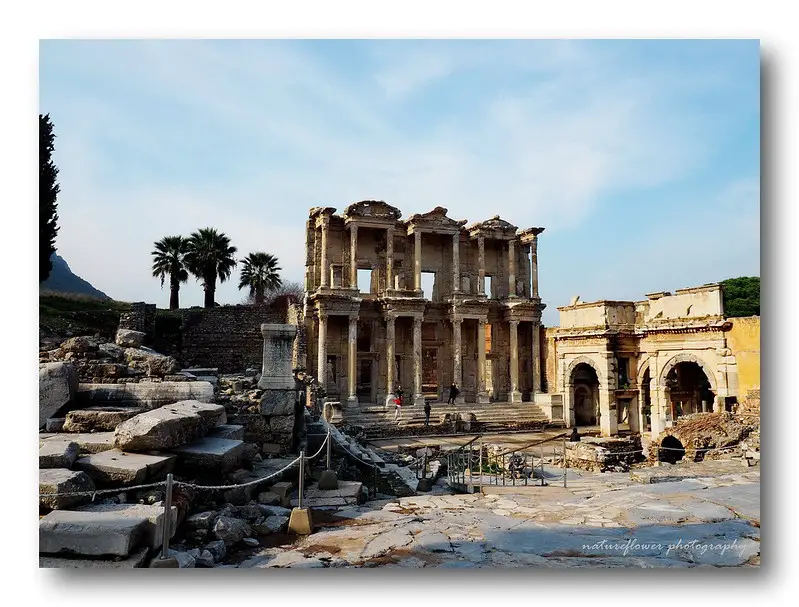

When we consider the olden Rome, our thoughts mostly think of images of grandeur, such as the Colosseum, the Pantheon, and other architectural marvels.

However, here’s a fact that our more glamorizing pictures of Rome regularly omit from the picture: from old times to the mid-twentieth century, the Eternal City was bounded by 310 square miles of marshland, called the Pontine Marshes. Now, you know the meaning: many and many mosquitoes.

As the Roman Republic increased in power and ultimately turned to be the Roman Empire, those malaria-laden mosquitos were some of the city’s ultimate helpers. Between 390 BCE and 429 CE, they protected against one attacker after another such as the Gauls, the Carthaginians, the Visigoths, the Huns, and the Vandals.

Few of those attackers, for instance, the Gauls, were able to dismiss Rome, however, consequently had to withdraw because their forces were so exhausted as a result of malaria. Others such as Carthaginians didn’t even get so far before the mosquitos affected them.

If not for those mosquitos, the Roman Empire might never have risen because the Carthaginian Empire might have damaged it while it was still a republic.

However, the mosquito showed an unpredictable ally. During the start of the very first century CE, the Roman Empire attempted to grow into central and eastern Europe by attacking the lands to the east of the Rhine River. There, the Roman legions encountered violent fight from Germanic tribes, who smartly enforced them into going into battle and basing in the area’s marshlands. You possible predict what occurred after: mosquito-borne malaria ripped through their ranks. This assisted the Germanic tribes to put them down, in spite of having weaker military forces.

A few of those same tribes would further add to the destruction of the Roman Empire a few centuries after groups such as Visigoths began attacking in 408 CE. Those attacks were the cause of one of a number of social pressures that jointly added up to a lot of stress for the empire to endure. Other causes of pressure are famines and epidemics, the latter of which was as a result of a combination of plagues and malaria.

Therefore, while it would be inaccurate to state that the mosquito led to the downfall of the Roman Empire alone, she definitely had an essential part to play in both its rise and its fall.

6 – Malaria added to the growth of Christianity and the abortion of the Crusades.

You’ve probably heard of the saying that goes thus “all roads lead to Rome.” The basic notion is that the Roman Empire connected a lot of Europe together. It linked that basically by roads, however, also economically, politically and culturally by trade and defeat. That laid the basis for the extensive spread of transmission of both diseases, such as malaria, with ideas, like those of Christianity.

The widespread of the disease assisted in the spread of the religion. Different from the Roman paganism, Christianity showed itself as a healing religion. The ancient Christians believed that they had a religious role to fulfill like caring for the sick people, and they also demonstrated what they preached by performing healing rites, offering nursing care and establishment hospitals. This enabled the religion to be very attractive to a lot of Europeans during the third century CE when the continent was afflicted with malaria and other epidemics.

Christianity started to become famous and at the end of the fourth century, it became the formal religion of the Roman Empire. During the time of the Middle Ages that followed its downfall, Christendom and Europe became basically the same.

However, after facilitating the increase of European Christendom, the mosquito also assisted to provide one of its utmost conquests. This occurred during the Crusades – a series of nine military journeys to the Middle East that a lot of Christian European armies started between the years 1096 and 1291.

The supposed aim of the Crusades was to “regain” the Holy Land of present-day Israel/Palestine and its environments– the Mediterranean area called the Levant, which the Muslims had been in charge since the upsurge of Islam during the seventh century. Setting aside their religious alleged reason, it was obvious that the Crusades was the first extensive effort of European powers to colonize lands beyond their continent.

However, it resulted in failure. Over and over again, the European armies were affected by malaria. The disease was prevalent in the wet, low-lying coastal regions of the Levant, where the Crusaders have a habit of gathering, much to the happiness of the local mosquitos. To show an illustration of the disastrous outcomes: during the Crusaders’ almost two-year attack of the coastal city of Acre from 1189 to 1191, nearly 35% of the Christian soldiers died as a result of malaria. By severely exhausting their army’s strength, the disease assisted to prevent their main goal of winning Jerusalem.

The Levant would continue to stay independent of European control until World War One.

7 – Europeans took malaria as well as other diseases to the Western hemisphere, destructing native societies.

You are possibly aware of what happened in 1492. the year that Christopher Columbus sailed west in order to find a short route to Asia, only to unintentionally come across an island off the coast of North America. However, it wasn’t only Columbus and his member who mistakenly got to the shores of the Western hemisphere on that crucial mistake journey; the mosquito-borne diseases –our most olden enemy, malaria was also there.

Before 1492, the Western hemisphere was the habitat to a lot of mosquitoes; however, they didn’t transmit any diseases. When Europeans and enslaved Africans got to the Americas, they accidentally took the disease-ridden mosquitos along with them.

Those mosquitoes either removed or infected the native mosquitos with their pathogens. Together with non-mosquito-transmitted diseases such as influenza and smallpox, mosquito-borne diseases immediately spread to the native people of the hemisphere. Truly, less than a year after Columbus’s member settled on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, the native people of Taino people were experiencing an awful epidemic of both malaria and influenza.

During the early fifteenth century, as Europeans began having a base on the coasts of the mainland of the Americas, the diseases they took along with them spread quickly to the inland, all thanks to the native trading networks that spread through the whole Western hemisphere. As soon as the 1520s, malaria, smallpox, as well as other diseases, may have gotten to the north as the Great Lakes and to the south as Cape Horn.

Therefore, the diseases behaved as a potent front for the attacking Europeans. Both in the southeast and the southwest of what is known now as the United States, whole native communities had been damaged or destroyed as a result of malaria long before Europeans even got to their lands. Also, a mixture of both malaria and smallpox destroyed the great Aztec and Incan civilizations during the 1520s and ‘30s.

Therefore, the Spanish conquistadores Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro were now capable of “defeating” these advanced multimillion-people-strong societies with only 600 and 168 soldiers, respectively.

The death and damage created by European-introduced diseases were destructive in scale. Between 1492 to 1700, the total indigenous population of the Western hemisphere fell by approximately 95 percent that is; from a population of 100 million to 5 million. The majority of the death rates were as a result of illness, instead of a military defeat.

Therefore, the mosquitoes including her diseases have a huge role for one of the greatest history’s disasters. Also, they assisted in making the way for European colonization of the Americas.

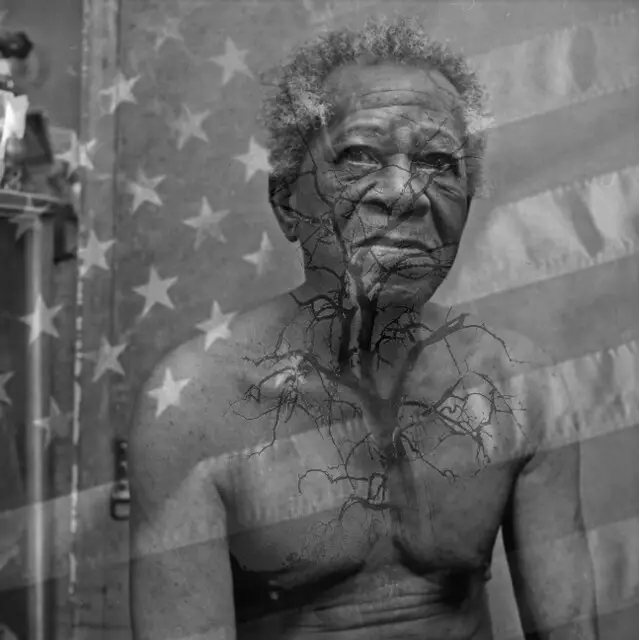

8 – During the time of the European colonization of the Americas, the mosquito had a part to play in creating both slavery and revolution.

During the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, similar to how Spain, Portugal, France, and Great Britain created and extended their colonies in the Americas, the European colonists experienced a key problem.

In regions like the Caribbean and the American South, they wanted to produce huge amounts of cash crops such as sugar, cocoa, coffee, tobacco, and cotton. However, in order to do that, they required the same huge amount of labor power. Initially, a lot of them turned to enslaved native people and European enslaved servants. However, those people that were enslaved and servants continued dying as a result of malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases, which flourished in the exact environments as the crops.

Due to that, enslaved Africans were seen as a much more steady and valued way of labor. The Africans were people from West-Central Africa and the majority of them were the offspring of people who had created genetic immunities to malaria thousands of years ago. This enabled them to be very much likely to withstand the mosquito’s deadly bite. Therefore, the mosquito had a huge impact to play in the rise and increase of Africans as slave labor during the European colonization of the Americas.

Also, it had a huge impact on the revolutionary wars that led to the end of colonization. Between the years 1776 to 1821, one colony to the other began revolting against their British, French and Spanish rulers. At first, it was the Thirteen Colonies that turn into the US, then Haiti and then the entire slew of South and Central American colonies, with Venezuela, Colombia, and Panama. The European powers tried to keep their colonies, however, they were prevented at almost every try by the rebels as well as their greatest ally: the mosquito.

With a blend of malaria, yellow fever, and dengue, the mosquito murdered or weakened a lot of the armies of the European empires during the revolutionary wars that cleared the Americas. Those diseases made 40% of the key contingent of British soldiers weak for service at one point in the Thirteen Colonies in the year 1780.

Also, between 1791 to 1804 during the Haitian Revolution, the French soldiers that went to the island, 55,000 out of 65,000 of them died as a result of mosquito-borne diseases. In 1793, after the British and THE Spanish joined the war, they took the mosquito’s death rate up to 180,000.

Certainly, the revolutions in the Americas only led to liberty for some people. Also, in the US, the enslavement of African peoples went on–however, during the American Civil War which was less than a century after, the mosquito would play a huge part in putting a stop to the terrible institution that it aided to start.

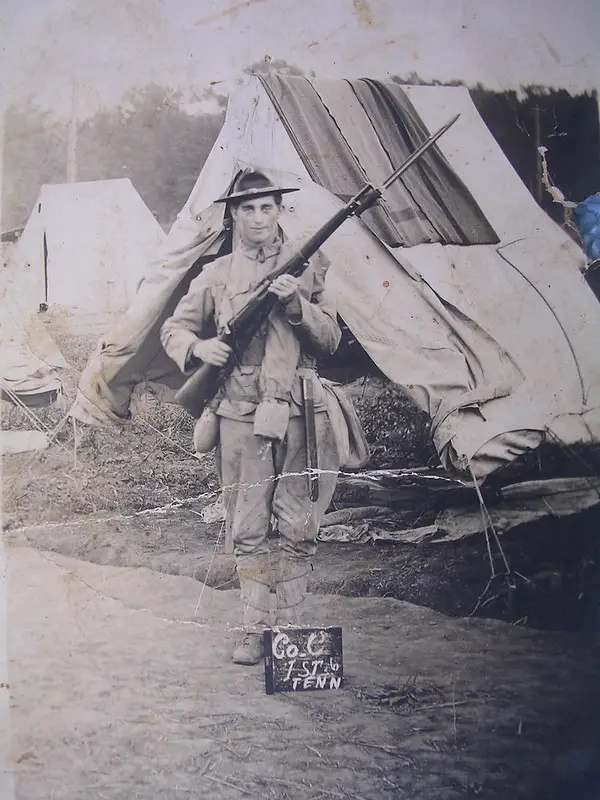

9 – By extending the Civil War, the mosquito assisted in bringing a stop to American slavery.

In 1861, when the American Civil War started, the rebelling southern Confederacy was weaker than its northern Union enemy on almost every front: weapons technology, military size, industrial development, infrastructure, natural resources – you mention it.

Under this uneven condition, President Abraham Lincoln wished for a fast resolution to the war. Thus, his primary aim was limited. He basically wanted to persuade the Confederacy to submit as soon as possible, in order to protect the United States. To him, that involved taking the South back into the fold and making sure things went back to the way it used to BE before the war started. He had no aim of destroying the South’s military, defeating it to Northern rule or putting stop slavery.

But, the mosquito changed that.

A group of 120,000 Union soldiers started to march near the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia in March 1862. On their way, they got caught up in a landscape that was filled with creeks and swamps. You probably know the meaning of that which is mosquitos and malaria. 40% of the Union soldiers were weakened as a result of illness by June 1862. The Confederacy used that change to create an attack against their enfeebled enemy, and the Union was coerced to withdraw.

About the exact time, a close story happened when the Union tried to capture the Confederate fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. In July 1862 at the end of that unsuccessful campaign, a surprising 75% of the Union soldiers had either been killed or weakened by mosquito-borne diseases.

After these main, mosquito-assisted defeats of the North, it was obvious to President Lincoln that the war wouldn’t be the instant and limited war he was expecting. Therefore, he had a change of plans and decided to greatly increase the Union’s aim to cover the total destruction of the Confederate military, the total defeat of the South and the elimination of slavery.

While there was a moral element to Lincoln’s aim of putting stop slavery, also, there was rational military reasoning behind it. He thought that by releasing the slave of the Southern states, the North would sabotage the South’s economy and the war power, both of which greatly depended on slave labor. He as well as his medical advisors also anticipated that the enslaved people that would be released would join the Union army and take their immunity to malaria with them.

As a matter of fact, a lot of the enslaved people’s immunity was lost as a result of genetic mixing since, for generations, slave masters had been raping them.

Eventually, 40,000 African American soldiers died while fighting for their liberty in the Union army – and also 75% of them died as a result of illness.

10 – The mosquito assisted the US to start its growth to global power during the Spanish-American War.

Immediately after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the US started planting the seeds from which it ultimately developed to be a global power. Obviously, it didn’t develop those seeds alone; it got huge help from our old enemy, the mosquito.

This is the story. As early as the 1820s, the US had eyes on Cuba, which was controlled by the Spanish then. Five presidents wanted to buy the island from Spain; five presidents’ offers were declined. In the 1870s, American corporations began putting capital into Cuba, and by 1877, the US was buying 83% of its exports. About that exact time, present and formerly enslaved people of African origin started to strike against Spanish rule in Cuba.

In 1895, the revolution exploded into a complete rebellion. Spain sent about 200,000 soldiers to the island in reaction to the rebellion. You won’t be surprised to know the next thing that occurred: the Spanish soldiers were destroyed by malaria and yellow fever.

Moving to April 1898, when the US announced war on Spain in the anticipation of putting an end to the Cuban war and defending its corporations’ investments on the island. At that time, 75% of the 200,000 Spanish soldiers that were sent to the Island were either killed or weakened – the most of them by mosquito-borne diseases. This made it easy for the US to conquer the Spanish with just 23,000 troops.

In August 1898 which was only four months after the Spanish-American War started, Spain admitted defeat, and Cuba was a US dependency until 1902 when the island was officially independent under the government of a US puppet.

First America’s huge progress onto the world stage was successful all thanks in no little part to the mosquito. Furthermore, to partly acquiring Cuba and completely gaining Puerto Rico, the US also attained the Pacific islands of Guam and the Philippines from the Spanish. During the same period, it captured Hawaii, reinforcing its rank as a burgeoning Pacific power. That made it on a clash with another rising Pacific power: Japan. If you know about World War II, you are aware of where the story is going.

However, that is not where we’re going. Rather, we’re going to go back a bit and explore another mosquito-driven twist of history that stemmed from the Spanish-American War. This one would change another war forever: that is among humans and the mosquito itself.

11 – Key developments were achieved in the battle against mosquito-borne diseases after the Spanish-American War.

Here’s a question from the last chapter: After wanting Cuba for a long time, why wasn’t it taken by the US at the end of the Spanish-American War?

That would have needed a US military job. And that, successively, would have involved exposing US troops to the exact mosquito-ruined fate as their Spanish enemies. Certainly, at the end of the four-month war, 4,700 US servicemen died as a result of mosquito-borne diseases – with yellow fever common among them. The US didn’t want to have more deaths; hence, it retreated its troops.

However, its corporations’ capital, military governorship and, after, its puppet government stayed in position; therefore, the US had a strong interest in maintaining the island – and that involved fighting back against the affliction of mosquito-borne diseases.

To that end, in June 1900, the US government created the US Army Yellow Fever Commission, which was controlled by Dr. Walter Reed. Under his direction, a group of scientists started to perform research on the hypotheses that the disease was caused by mosquitoes.

As of then, a lot of people were really uncertain of this notion. For more than 3,000 years, the main reasoning for mosquito-borne diseases had been thought to be a result of the miasma theory. According to this theory, the diseases were a result of some kind of mysterious fumes that stemmed from stagnant bodies of water.

Then, by 1897, a number of diverse European scientists working in numerous European colonies in Africa and Asia had already found that the mosquito and its parasites were the cause of malaria, therefore, the idea of the miasma theory was declining. In October 1900, Dr. Reed and his team assisted to condemn it when they declared they’d found perfect evidence that mosquitoes were also the ones behind yellow fever.

The declaration also urged another doctor whose name was Dr. William Gorgas into action against the mosquito. He was the chief military sanitary officer of the Cuban capital of Havana. Under his direction, a group of “sanitation teams” created a full war against the mosquito. They created various methods such as draining swamps, reducing stagnant water found on the streets, the introduction of mosquito nets and using a series of chemical agents like sulfur, chrysanthemum-pyrethrum powder, and pyrethrum-laced kerosene.

Yellow fever had disappeared from Havana by 1902, and by 1908, the whole island of Cuba was free from its.

12 – In and between World War One and Two, mosquito-borne diseases struck back more.

After Dr. Gorgas’s huge success in Cuba, the US government posted him to Panama, where he applied the same methods he’d created in the Caribbean to keep away mosquitos during the construction of the Panama Canal.

After the completion of the canal in 1914, the importance of the accomplishment wasn’t a situation of just engineering; it also signified a historic triumph against humanity’s worst adversary. Spain, Scotland, England and France had all formerly attempted to colonize Panama –in which all of them had been bloodily discouraged by mosquito-borne diseases. All thanks to Dr. Gorgas’s mosquito-fighting actions, the US was now capable to eradicate yellow fever completely and also able to lessen malarial infections of the canal’s workers by 90%.

After making way between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans for the first time in humankind history, the US now has an important benefit that really enhanced its increase into a global superpower.

Now, we’re in the twentieth century, therefore, you know what is occurring next that is World War I and II. However, here’s the shock: for the first time, the mosquito didn’t have a great impact on the following wars. During the First World War, below one percent of the entire deaths were, as a result of mosquito-borne diseases. Compare that to the large rates of about 90% that had afflicted both sides of the Spanish-American War, only two decades before.

All thanks to the effort of Dr. Gorgas, Dr. Reed and a lot of other scientists and doctors, like the Italian zoologist Giovanni Grassi and the British doctor Ronald Ross, Western militaries were now very effective at solving the issue of mosquito-borne diseases.

With a combination of funding from government and charitable organizations, scientific research on fighting mosquitos as well as their diseases went on to both World Wars and the inter-war period. This research caused the creation of synthetic antimalarial drugs like chloroquine and atabrine, which replaced quinine. They are naturally gotten from cinchona bark, quinine which had used for the past centuries; however, there was an inadequate supply as a result of the problem of cultivating cinchona trees.

Also, the research caused the finding – or rather, finding again – of an insecticide that appeared like a miracle key to the issue of mosquitos. It was known as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. Luckily, that chemical has a shorter name, which you probably know: DDT.

In the following chapter, we will talk about that story.

13 – Due to the effectiveness of DDT and antimalarial drugs, the potency of mosquito’s reduced and then reemerged during the twentieth century.

In 1874 for the first time, a duo of German and Austrian chemists produced DDT–however, they didn’t know its extreme superpower which is the killing insects.

The detection of DDT’s insecticidal power wouldn’t be known until 1939 when it was discovered by a German-Swiss scientist named Paul Hermann Müller. All thanks to his Nobel Prize-winning research, Western governments, militaries and farmers alike got to know that DDT was fatal to a lot of deadly insects, like Colorado potato beetles, fleas, lice, ticks, sandflies and, of course, mosquitos.

Between the years 1939 and 1955, DDT’s use gradually increased extensively. US soldiers sprayed it all around the Pacific and Italian battleground of World War Two. Also, American farmers sprayed it on their entire grounds. Even the US Centers for Disease Control sprayed it across 6.5 million American houses. And the World Health Organization sprayed it over big swathes of Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

The outcomes were surprising. In developing countries, cases of malaria reduced at rates from 35 to 90 percent, depending on the region. In Europe, malaria was completely eradicated by 1975. Also, worldwide, between the years 1930 to 1970, the entire cases of mosquito-borne diseases fell by an unbelievable 90%.

With the mixture of DDT, man-made antimalarial drugs and the range of anti-mosquito methods created since the turn of the twentieth century, mosquito’s looked to be vanishing.

However, the mosquito fought back. Actually, its reappearance had been developing for some time. In the 1960s, a lot of the insect population started to form resistance to DDT across the globe. Also, the chemical was on fire from environmentalists –the biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson, who explained in her extensively read and extremely influential book Silent Spring that was published in 1962 the negative environmental impacts like damaging the populations of the bird.

A decade after, in 1972, the US prohibited the domestic usage of DDT, and a lot of governments around the world did the same thing.

The blend of DDT’s loss of efficiency and the end of its usage caused a worldwide re-emergence of mosquito-borne diseases. The rates of the diseases went back to their pre-DDT levels during the early 1970s in countries like Latin America, the Middle East, and Central Asia. On the other hand, the malaria parasite was evolving and forming resistance to antimalarial drugs. During the mid-1980s, chloroquine had become impotent around the globe and mefloquine was also becoming less potent.

As we’ll find out in the following and last chapter, the outcomes have been devastating and the epidemic still remains in our society up till now.

14 – The history of the mosquito’s effect on mankind is yet to be written.

Ever since the reappearance of mosquito-borne diseases during the 1970s, the most popular cases of malaria have happened and keep happening in extreme disadvantaged regions of the world like sub-Saharan Africa. 85% of all cases of malaria occur in sub-Saharan Africa, while 55% of the county’s population survives on less than $1 daily.

Missing a profit drive, pharmaceutical companies have used very small money on researching and creating new antimalarial drugs to substitute the ones that have become ineffective. In the twenty-first century, non-profit organizations like the Gates Foundation have gotten involved in order to fund antimalarial research, however, there’s no effective cure yet.

All thanks to 28 years of improvement and $565 million funds from the Gates Foundation and other organizations, the first-ever malaria vaccine, Mosquirix, got to its last phase of clinical pilot trials in 2018. However, its effectiveness seems to be short-term: only 39% after four years and just 4.4% after seven years. The malaria parasite changes so fast that it’s extremely hard to destroy it for long.

Therefore, its death rate continues to increase. From the twenty-first century, an average of two million African people dies every year as a result of malaria.

However, presently, there’s a new viewpoint on the horizon which is the genetic-engineering technology called the CRISPR. With this knowledge, scientists can now interfere with the DNA of male mosquitos in the laboratory and then free a group of them into the wild to copulate and transmit their human-changed genes. That would create the opportunity for two likely objectives that scientists, governments and non-profit organizations could follow.

Firstly, the mosquito could become less potent of transmitting malaria, maybe by letting its salivary gland end the parasites before they get the opportunity to be transmitted. In terms of interfering with nature, that would be the greatest harmless opportunity.

Secondly, the mosquito could be re-engineered to have stillborn, infertile or totally male offspring, which would lead to its extinction in a few generations to come. A world free of mosquito might seem like a dream come true, however, we are not aware of what the outcome might be on the Earth’s ecosystems and the natural balances that keep them.

The decision is up to us– and with it, the history of humanity’s connection to the mosquito could end to an intense apex in the following years.

The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator by Timothy C. Winegard Book Review

Surviving in wet, warm environments and spreading a range of deadly diseases, like yellow fever and malaria, the mosquito has been affecting humans for thousands of years now. By causing the deaths and weakening huge percentages of the soldiers who occupied the ranks of various attacking armies, it has determined the faith of a lot of wars, empires and military fights.

Also, the mosquito has offered an extensive historical improvement such as the emergence of European colonization in the Western hemisphere, the destruction of native populations in the Americas, the entrenchment of enslaved African labor and the rise of the United States as a world power. Great developments were created in fighting the mosquito and its diseases during the early and mid-twentieth century, however, since that time; they’ve been reoccurring. The future of human association to the mosquito has to be written – perhaps by genetic engineering of the insect’s DNA.