At a point or the other, nearly all Westerners have made use of the term Zen during a discussion. Maybe a room someone is sitting in feels really Zen, or she’s going to have a calming weekend attempting to regain her Zen.

In the West, there’s an unclear idea that Zen has a thing to do with peace, calmness, and quietness. However, how correct is this knowledge?

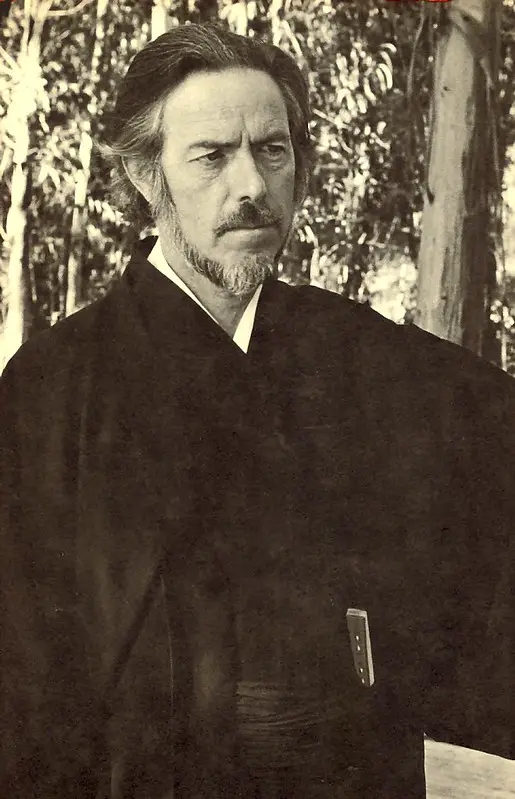

Westerners usually have problems wrapping their heads around the abstract thoughts that constitute the essence of Zen thought, some of which look paradoxical. However, luckily, writer and thinker Alan Watts is here to clarify the subject and discuss its paradoxes.

In the next chapters, you’ll learn about Watts’s idea of the history of Zen, beginning with its origins in Chinese Taoism. Also, you’ll examine some of the key principles of Zen. In the end, you might see yourself viewing the universe just a bit differently.

Chapter 1 – The original basis for Zen Buddhism was set by the Chinese Taoist philosophy.

Do you understand how to breathe? Definitely, you feel as though you understand how to breathe –nevertheless, you’re doing it frequently. However, if you needed to describe the actual physiological processes that let you breathe, you might be somewhat lost.

What Westerners consider as knowledge is concrete and fact-based. Still, few individuals in any part of the globe would mention that they don’t understand how to breathe, move their legs, or see. Therefore, as a matter of fact, what you understand forms a lot of things about whose actual workings you have no idea. Immediately you know this, you’ll know the notion of knowledge in Taoism, one of the key ancestors of Zen Buddhism.

The original origin of Taoist thought is a vital book known as the I Ching, or Book of Changes, written in China somewhere around 3000 and 1200 BC. The book mentions an approach of divination in which an oracle “sees” a hexagram pattern first somewhere in his surrounding. Afterward, he matches the hexagram’s features to those in the I Ching to foretell his subject’s future.

Now, you may not trust in making choices based on an oracle’s forecast of your future. However, is your approach to decision-making any more logical? You might want to say yes. However, how do you know the precise point at which you’ve gathered sufficient information to make a choice? Aren’t there usually more details you could collect so as to make an even more “rational” decision?

In order to make a really fact-based choice, it would need a really long time –provided that the time for action would have gone by the time you’d collected the entire information.

Our choices eventually boil down to a feeling about which decision is correct. Good choices rely on good intuition – or, as a Taoist would mention, being in the Tao. If you’re in the Tao, your mind is clear and also, your intuition is at its most effective.

Consider it in this manner: There’s no amount of work you can do to make it mandatory for the muscles in your tongue to taste more precisely. You only need to believe in them to do their work. Similarly, you must be able to trust your mind.

Clear-mindedness, as well as trust in the mind’s natural skills, would later become fundamental to Zen. However, before we move there, let’s examine the roots of Buddhism.

Chapter 2 – Buddhism was the main philosophy from which Zen developed.

Based on the Buddhist tradition, during one evening, the Buddha sat under a tree after seven years of meditation and modest living. He had been doing the whole right practices to teach his body; still, he still couldn’t discover his actual Self. Therefore, ultimately, he basically surrendered and chose to eat some nourishing food underneath a towering tree.

While he was sitting under the tree, Buddha discovered immediate clarity. He discovered that provided man continue to attempt to understand what his own life is, he will not succeed. This part of Buddhism – the unexpected awakening –ultimately became a vital part of Zen. The Buddha stayed in India sometime between the fifth and fourth centuries BC, the first Buddhist text known as the Pali canon, wasn’t written until some 400 years after. Formerly, Buddhism had lived just as an oral tradition. This makes it hard to know the outlooks of Buddha himself; however, we can still tease out the most vital ideas.

All through the entire Indian thought is the idea of God’s self-sacrifice or Atma-yajna. In creating the universe, God is shattered and broken into various pieces. Every being has a part of God, and our life’s goal is ultimately to reintegrate with the One.

Therefore, in Buddhism, understanding yourself entails understanding your original identity – God. In order to do that, you have to separate your self from every kind of identification. You’re not your thoughts, your body, or your emotion. Also, you’re not your roles, such as a mother or doctor.

Observe that Buddhism lays a huge emphasis on negative understanding–meaning, understanding what you aren’t as opposed to what you are. This can be perplexing to Westerners, who have a tendency to anticipate concrete definitions.

However, the universe isn’t usually as concrete as we’d expect it to be. For example, you can say that the First World War started on the 4th of August, 1914. However, did it actually happen then? A historian can show causes for the war from way before its official start date.

Therefore, we can see that divisions of things, situations, and facts are formed by arbitrary human accounts – not by reality itself. An Indian Buddhist would refer to these artificial divisions as Maya or illusion. Also, the purpose of our lives should be to free ourselves from these illusions.

Chapter 3 – Mahayana Buddhism provided a resolution to the psychological problems in traditional Buddhism.

When individuals that are asked the Buddha questions regarding the nature of the self and the beginning of the world, he told them those kinds of questions were not relevant. Asking questions like that wouldn’t bring about liberation.

However, some Buddhists –people who would turn into the Mahayana – were not willing to accept no for an answer. Mahayana Buddhists still pursued liberation and weren’t intending to form a totally new philosophical system. However, they were extremely concerned about their own psychology. This dissimilarity between Mahayana Buddhism and traditional Buddhism was vital to the later Zen tradition.

Mahayana Buddhism separated from traditional Buddhism somewhere around 100 and 300 BC. In some means, Mahayana was a reaction to the people searching for an easier way to enlightenment – one that they could achieve in this life instead of after numerous lives. Mahayana wished for enlightenment to be available to everybody.

Although available, the route to enlightenment in Mahayana is still anything except easy. In order to know about Mahayana beliefs, you’ll have to follow some difficult logic, so be ready.

First of all, you have to know that trying to understand reality is not possible.

If understanding reality itself is not possible, how then can you perhaps anticipate understanding enlightenment? It would be weird to see enlightenment as a thing to be acquired.

Also, in the same manner, because reality is illusory, your ego as well must be an illusion. This eventually signifies that you cannot achieve enlightenment since the idea of you is not real.

Therefore, now we’ve reached the core of the argument. If enlightenment is not something that can be gotten, and if no individual entities are real, then we ought to already be in a state of enlightenment! To search for enlightenment would be to search for a thing we’d never lost.

You might be wondering– okay, easy; therefore, I should put a stop to attempting to reach enlightenment. However, you’ve gotten yourself in a double-bind. By attempting not to make an attempt, you’re still making an attempt. You’re still driven by your urge to attain enlightenment, maybe it’s through understanding or not understanding.

In order to actually follow the Mahayana, you need to release yourself from the motivation to reach enlightenment. You can’t probably long for the actual enlightenment since it’s not possible to understand what that enlightenment is. Also, by attempting to become Buddha, you’re refuting that you’re a Buddha already. This belief is vital to Zen.

Chapter 4 – Zen started in China with the work of some knowledgeable monks.

The story goes thus; the Indian monk Bodhidharma took Zen to China during the 520 AD. When he got there, Bodhidharma went to the court of Buddhist emperor Wu of Liang. However, it’s said, Emperor Wu didn’t like the principle or the approach of Bodhidharma’s. Therefore, Bodhidharma retreated to a monastery. There, he came across a monk Hui-k’o, who would ultimately turn out to be the Second Patriarch of Zen in China.

Although this origin story is usually told in the Zen School, its historical precision is extremely suspect. Rather, we might discover the actual roots of Zen in the teachings of a young monk called Seng-Chao, who stayed in China around 400 AD.

Some of Seng-chao’s principles played a vital part in the later growth of Zen.

One of certain importance was his outlook on time and change. Westerners are accustomed to viewing life as a type of progression – for example, they feel that day turns into night, and winter turns into spring. However, for Seng-Chao, each moment stands on its own, with no connection to either anything before or after. Likewise, in Zen, there is no reality aside from that of the present moment.

Some hundred years after Seng-Chao, there was another monk called Hui-Neng. It was said that Hui-Neng was accountable for starting the idea of chih-chih. This word implies the demonstration of Zen with nonsymbolic words or actions.

To someone that is not familiar with Zen, chih-chih can look a little bit nutty at times. For example, a Zen master might be told to answer a spiritual question regarding Buddhism. In reply, the master makes a spontaneous comment about the weather. These answers cannot be further clarified– either you instantly get the point that was made, or you don’t.

For instance, consider the monk Chao-chao’s reply to a question about the spirit: “This morning it’s windy once again.”

Therefore, what precisely is the aim of this rare question-and-answer format? Well, recall that whatsoever the Zen master mentions or does is believed to be an expression of his Buddha-nature. Just like every other thing on earth, his words, as well as behavior, seem spontaneously from nothing, without consideration.

Upon his death, Hui-Neng transferred his viewpoint on to five followers. The teachings of two of these followers are still present up until now as the two principal schools of Zen in Japan.

Chapter 5 – Zen assists us to destroy the illusions our minds have formed.

For a lot of individuals, the main purpose in life is easy: to be happy. However, what really occurs after you accomplish that happiness?

In the philosophy of Zen, the quest for happiness is regarded as absurd. It’s really the outcome of a wrong premise: that it’s likely to feel just the good, with none of the bad.

You might liken the quest of happiness to moving from left to right on a hard bed. You’re not comfortable on the right side of the bed, and that makes you turn to the left. At first, that seems good; however, the left begins to feel just like the right. As a matter of fact, the sole reason you can know the feeling of comfort is that you understood discomfort first.

Therefore, discomfort is not just unavoidable but basically another part of comfort. This might direct you to the think that we do not have any free option, that we’re left to whatsoever fate that lies waiting for us. However, that idea is grounded on another wrong premise.

In Zen, it’s not possible to be a helpless victim of your situation. As a matter of fact, you as well as your situations are really not separable.

Visualize a hot day in midsummer. Your body is dripping with sweat. Zen would tell you that you aren’t sweating due to the reason that it’s hot outside. Instead, the sweating is the heat.

You can think about your mind and body through this exact framework. Your mind-body can’t be given a range of situations. Rather, the situations occur due to the fact that you have a mind and body that can notice them.

You might have a tendency to refer to this perceiving entity – this mind and body of yours – your self. Still, the self is yet another illusion that Zen can assist us to disintegrate.

When you are told to yourself, you might mention various adjectives. Or perhaps a few past occurrences that look to define who you are. However, are any of these descriptors real in the truest sense of the word? In a word, no.

We have powerful minds, and they let us form a symbolic type of ourselves that isn’t really real. However, this idea of our self is not tangibly linked to what our minds and bodies are feeling at the moment.

So, in Zen, the actual you are basically the sum of everything of which you are conscious of at this actual moment.

Chapter 6 – Naturalness, as well as spontaneity, are vital in Zen

A key concentrating of Zen is naturalness, or not endeavoring to “be” anything particularly. Somehow, Zen is essentially about letting yourself be aimless – basically, to do nothing.

Not doing anything might seem like a big waste of time to a Westerner. However, as a matter of fact, it’s the natural state of most everything in the universe. A cat doesn’t attempt to be anything but a cat, and your ears don’t attempt to do anything but hearing. Zen informs us that we should let our minds work in the same manner: as naturally and spontaneously as possible.

In Zen, any feeling you naturally show in reaction to a situation is valuable – and it is valuable due to its naturalness.

Consider the story of a Zen monk who started crying after finding out that a close relative of his had passed away. A student stated that it was inappropriate for a monk to respond like that. However, the monk responded by saying, “Don’t be stupid! I’m crying because I want to cry.”

Definitely, our deeds, can still be right or wrong in the common moral sense. However, in Zen, anything we do, and anything that occurs, is right in the sense that it’s natural.

It’s not only our deeds that should be natural and spontaneous. It’s our words, as well.

For instance, when Zen master Yün-men was told to mention the vital secret of Buddhism, his answer was, “Dumpling.”

Here, Yün-men’s mind acted totally by itself. Also, during the process, it showed an underlying fact – one that a normal person might not know; however, that can just be conveyed by the one word “dumpling.” This would never have occurred if Yün-men’s mind had been disturbed by affectation.

Also, Spontaneity also spreads naturally to the Zen notion of satori or unexpected awakening.

Satori is less like complete enlightenment and more like an outburst of insight. It can take the shape of a great realization – it may be a thing you instantly know about the deepest beliefs of Buddhism. However, you can as well go through less-monumental moments of satori, such as the instant remembrance of a long-forgotten name.

With this whole emphasis on spontaneity, you might infer that Zen supports yielding to desire. However, this is very far from the situation. Rather, Zen is essentially about taking out mental blocks, letting your mind to work in its freest, most natural state.

Chapter 7 – Meditation has to be basically about sitting and noticing the universe, precisely as it is.

If you practice meditation at the moment, what is your purpose when you sit in silence? Maybe to cleanse or clear your mind, or to accomplish some kind of knowledge that stays elusive.

For Zen, every goal linked with meditation is mistaken. For example, in Buddhism and Taoism, the purpose of sitting meditation is to clear the consciousness and clean the mind. However, in Zen, our nature is pure already– it’s already Buddha. Also, if you attempt to clean it, you’re really polluting it with your desire.

Sitting meditation, or za-zen as it is referred to in Japanese, may not have had a lot of importance for the original Zen thinkers. However, in this present Zen communities, it’s extremely significant.

In Zen, it’s vital to sit and watch the universe so as to really experience it. Nevertheless, does the universe occur just when you think and do things in it? Definitely not.

You can consider your mind as a muddy river. As you carry on with your life, your mind gets muddied. However, what occurs to muddy water when it’s left alone? Ultimately, the dirty and residue sink to the bottom, and the waters stay clear. In the exact matter, when you meditate, your mind is left alone to remain clear.

However, practicing za-zen doesn’t essentially signify sitting and intentionally attempting to think about nothing. Doing that would be counterproductive. Also, it is not about focusing on any one thing specifically, such as your breathing. Rather, it’s basically a quiet awareness of whatever occurs in the present moment. You as well as your external world are one, and you do not have any purpose in mind as you sit and watch.

For the students in Zen schools, if there’s any purpose to the practice of za-zen, it’s to be more capable of answering the koan. These are hard philosophical questions in which there are no officially published answers. As a student grows, he is asked more and more tough koan for which he has to give more and more creative answers.

For example, a student of Zen might be told, “Take the four parts of Tokyo out of your sleeve.” This koan may be solved by removing a paper handkerchief and separating it into four.

In order to the koan, a student’s mind has to be clear and sharp – a state that za-zen assists it attain.

Chapter 8 – Zen art makes use of emptiness to make a strong influence.

There is an expression of Zen that says that “one showing is worth a hundred sayings.” Also, there is maybe no better means to reveal an idea than through art.

The main point of every Zen art, maybe in painting or poetry, is the purposeless life. What Westerners might refer to as an empty or worthless existence is essential, in Zen, one of limitless freedom. Zen art arouses that sense of happiness in freedom by making use of the evocative power of empty space.

Sumi-e is a calligraphic form of painting that deeply shows the feeling of Zen. The paintings of Sumi are painted with just black ink only, and the ink’s tone is diverse by the quantity of water with which it’s diluted. Normally, just one little portion of the canvas is painted, whereas the remaining may just be treated with a slight ink wash. This method lets the empty space in the canvas come alive, looking to be covered in the gentle mist.

The emptiness in paintings of the Sumi reflects the Zen principle of spontaneity. The little, painted portion of the image seems to appear from nothing.

In a related manner, Zen poetry reveals a great deal while saying just a little.

At a point, you’ve most likely come across a haiku, a short, three-line poem normally with nature as its subject. However, you may not have understood that haiku are outcomes of Zen thought.

A bad haiku is clunky and attempts really hard to say a thing that is significant. However, a good haiku throws a stone into the calm waters of a listener’s mind. It mentions just sufficient to be evocative while allowing the listener’s mind to do the majority of the interpretive heavy lifting.

Apart from painting and poetry, Zen thought fills architecture, particularly in the garden. In a garden of Zen, you would feel the ambiance of nature without being overwhelmed by ornamentation. Even in a garden that doesn’t have any water traits, your mind has to be able to summon the soft lull of a mountain stream.

Maybe it is in architecture, poetry, or painting, the process of Zen is at work. By noticing the momentariness and spontaneity of a haiku or Sumi painting, we’re brought directly with the current moment. Through that, we learn to free ourselves from time, and to understand the extraordinary information that the only reality is in the current moment.

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts Book Review

Zen Buddhism was formed by the philosophies of Taoism and Mahayana Buddhism. Ultimately, Zen developed into a lifestyle in its own right, with the main concentration on naturalness, spontaneity, as well as aimlessness. With a knowledge of Zen, you can liberate yourself from the delusions and wrong assumptions that hinder you from going through true reality –which is, the present moment.

Breathe easily.

Zen is essentially a philosophy of mind. However, if there’s a physical part, it’s most likely in the breath. In order to breathe just like a Zen monk, visualize your body being emptied of air by a huge lead ball sinking from your chest to your abdomen. Afterward, let your following breath to flow in as a reflex action. However, be cautious– as, in other parts of Zen, you don’t have to strive really hard to “master” this approach! Rather, attempt to watch your breath come and go, and allow it to occur naturally.