Like pedants, rulebook authors, and might be Canutes would want to reverse the situation of progress, how we talk changes constantly – languages keep changing.

English is one of the most dynamic languages. In its 1,400 years of evolution, it’s created wipes like characteristics of retention and an unbelievable skill for development. From articulation to accentuation, the English spoken today is very different from the English used by Shakespeare in his works.

Recognizing the history of change encourages us to put a few legends to sleep. From emojis to twenty to thirty-year-olds incessant utilization of “like,” the latest augmentations to English don’t subvert the language however proceed with its interminable custom of transformation.

Also, that is the genuine steady in English – change!

Chapter 1 – Passionate self-articulation may be fresh in workmanship, yet it’s been fundamental to the language since the Dark Ages.

Some of the time it seems like each subsequent individual needs to be a craftsman nowadays. The reason for this is that it’s one of only a handful of hardly any positions that truly support passionate self-articulation.

However, craftsmanship wasn’t generally similar to that. Feelings just became the overwhelming focus reasonably as of late.

Medieval artists, like Giotto di Bondone who was a Florentine painter in the thirteenth century, weren’t too intrigued by how people felt. The great questions of human life occupied them. Most importantly, that implied religion.

Things started to alter in 1505 when Leonardo da Vinci painted his famous Mona Lisa. The piece is acclaimed for its subject’s demure grin. The person is up front, making the canvas truly atypical, and consequently, it’s regularly viewed as denoting another, more individualistic time in human expressions.

From that point forward, there was no returning. From the Renaissance to Tolstoy’s cozy 1877 work Anna Karenina, people and their emotions have had pride in a spot in our craft.

While uniqueness and communicating feelings are moderately ongoing marvels in workmanship, they’ve been integral to how we represent hundreds of years.

Take “well.” Old English speakers were using old English in the early archaic period, however, they spelled it “well.” So I don’t get its meaning?

Think about the sentence “Well, ponies run quickly.” Imagine attempting to disclose to a little child what is the meaning of “well” here. Entirely precarious, correct? That is because, in contrast to “horse,” it’s difficult to think of it in a single concept.

It just truly bodes well with regards to a past comment or question, similar to “For what reason wolves don’t eat horses?”

The thing it recommends is a demeanor. By utilizing “well,” the speaker acts kindly in the face of another person’s ignorance about a specific subject. That implies this little word does a ton of substantial passionate lifting. It allows us to correct somebody without culpable him.

That causes it to be a special articulation of how our sentiments and feelings are inserted in the language we use!

In the accompanying parts, we’ll dive a little more profoundly into the emotional universe of emotions in language.

Chapter 2 – Emojis are only the latest expansion to the enthusiastic stockpile of our language.

There’s a particular kind of phonetic conservative who stresses that emojis will come to supplant composed English.

In any case, that is an implausible thought. Emojis are a method of infusing emotions into messages, not supplanting them!

How we talk is normally more meaningful compared to the written language, yet a massive shift has happened in composed language. Messaging makes composing considerably more like talking: it’s easygoing, snappy, and more passionate.

Contrast that with faxing: That may appear to be a prior form of something very similar, however, there’s a significant distinction. Faxes were for the most part used to pass on specialized substances, similar to guidelines or other data.

Faxes, so, were generally quite dry. Messaging is an alternate ball game through and through. Today, another age of innovation clients is making correspondence and a lot hotter and more close to home undertaking.

Also, that is the place emojis step in: emoticons fill a specific need – communicating feelings. Yet, the meaning of that isn’t their replacement of written language. If we just utilized emojis, we wouldn’t have the option to state without a doubt. Sentences would be like, “Well, better believe it, I surmise, that was absolute, you get me.”

So do we need all this fuss?

One explanation is that emojis are extraordinary. For one, emoticons are sketches. In any case, on the off chance that we set that aside, we can see that they regularly work similarly to words.

“Well,” like in the past section, is one model. Be that as it may, there are a lot of others. Simply consider late options to English, for example, “totally” and “like.” Then there’s the new utilization of “ass.” Added to a descriptor, it increases the significance. “Meanass,” for instance, signifies “amazingly mean.”

Different languages have comparable words.

The Germans sprinkle their sentences with “mal” to communicate nice easygoing quality. Japanese speakers include the “new” molecule to the furthest limit of sentences. When you ask them the meaning, you’ll hear a great deal of umming and ahhing. It’s an enthusiastic world – its exact significance is hard to nail down.

Chapter 3 – The importance of practically every word alters steps by step after some time.

If you’ve ever traveled back in time to the 18th century and offered a chocolate cake to someone, she may well decay by saying, “Pass, I’m lessening.” As you’ve likely previously speculated, that would have been her method of saying he was on a tight eating routine.

That is only one model. The importance of basically every word alters after some time.

Truth be told, the genuine anomalies are the words that hold their unique importance as the centuries progressed.

Take the thing “brother.” It’s meant something very similar for an astounding 7,000 years!

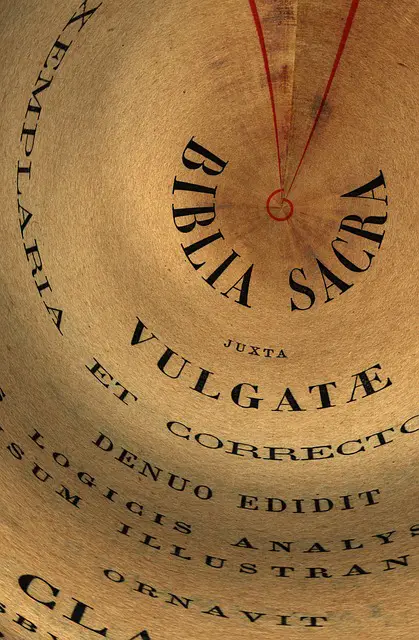

The word was first utilized by a clan living in present-day Ukraine. They talked about what etymologists allude to as Proto-Indo-European – the antiquated language from which most current European languages are dropped.

Another example is “I”. Since the beginning of its usage, it’s constantly signified “I,” even as its articulation altered. Proto-Indo-European speakers, for instance, would have likely articulated it as “eg.”

Yet, most words do change. In Shakespeare’s age, “science” implied information by and large. The screenwriter’s counterparts would have been bewildered by our utilization of the word to allude to the methodical information on the common world.

Or then again take the things “canine” and “dog.” In the middle age time frame, the previously alluded to especially enormous and threatening canines, while “dog” was the nonexclusive term for everything canine. Today, that has been turned around.

As that model proposes, etymological change is regularly a moderate consuming cycle. Words bear new implications for hundreds of years.

You can understand this by taking a gander at the historical backdrop of “innumerable.” In modern use, it fundamentally signifies “a ton,” or an enormous number. Yet, initially, it alluded to something that couldn’t be checked. That might’ve been things of which there were a lot of or something more unique which couldn’t be isolated into calculable units.

So, if you were a medieval person, you may have said something like, “My adoration is uncountable.” At the end of the day, “My affection can’t be tallied.”

After some time, notwithstanding, the primary sense won out. “Innumerable” began being utilized to allude to things that were so abundant you were unable to count them. At long last, that was the world’s just important. It no longer signified “uncountable” however “a ton.”

Chapter 4 – English is brimming with instances of action words turning out to be things and bear altogether various implications.

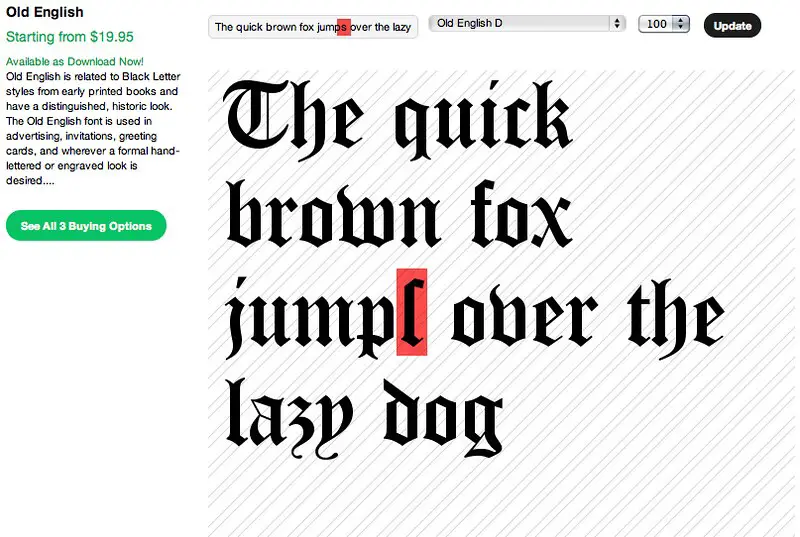

Perusing Shakespeare can be a peculiar encounter. Half of it is plainly English and promptly justifiable, however, the rest should be Greek.

This proves that phonetic advancement can likewise be a genuinely fast undertaking.

One way English has been altering as of late is by including new things gotten from action words.

In case you’re in a conference, for instance, you may hear somebody ask what “the ask” is, or if there’s “a fathom” for a specific issue.

That is quite exceptional to English. In contrast to a lot of different languages, word endings don’t give a very remarkable sign regarding whether they’re action words or things.

Take “scratch” or “walk.” We’re so used to sentences like “She had an ungainly walk” or “He has a scratch on his arm” that we don’t give any consideration to the way that the two things began as action words.

Yet, French or Spanish talkers could discover a change like that jostling.

That is because action words in French and Spanish are unmistakably stamped. You can recognize an activity word by its “er” finishing, as in “manger” in French. It’s “ar,” as in “hablar,” that is the giveaway in Spanish. Action words are simply too “verby” to twofold as things.

However, English doesn’t simply create new things out of action words. After some time, these new words bear various implications.

We should return to our prior model. A few people may contend that the sentence “What’s the problem?” could simply utilize a current thing – “solution.”

In any case, look all the more carefully. The two words aren’t generally equivalents by any stretch of the imagination. “Arrangement” is like the classroom. It’s the response to an issue in a bit of math schoolwork, not what hardcore finance managers are searching for in the meeting room.

They don’t need a solution, it’s a “tackle” – the response to a solid and commonsense issue in the relentless, merciless universe of business!

Chapter 5 – The importance of outcry marks has altered after some time and because of contact with different societies.

Design is broadly whimsical. It isn’t old that wearing dungarees checked somebody out as an individual from the in-vogue cutting edge. Today, pants – as we presently call them – are about as uninteresting as it gets.

The language additionally has its trends. Semantic styles travel every which way. Not even accentuation is absolved from evolving tastes. What’s more, there’s one accentuation mark that has altered more than most: the outcry mark.

Messages and instant messages are loaded with them. Indeed, even eatery receipts can’t avoid their charm, with models like “Tell us your thoughts of our administration!!”

They’ve become a standard charge. Typical contractions like “OMG” just couldn’t be finished without various outcry focuses.

So what’s happening? Are individuals essentially substantially more excited about existence nowadays?

A superior answer is swelling. The once infrequently located exclamation mark doesn’t have the same power since it began being utilized so often. It doesn’t convey incredible astonishment or accentuates a solid point anymore, yet has taken charge as a sign showing that we’re focusing.

As it were, it’s about consideration. Essentially messaging “see you there” conveys an insulting message. Including a shout, the point is de rigueur on the off chance that you don’t need the beneficiary to feel like she’s been treated with complete disdain.

That is an alteration in regular use that has been driven by contact with various societies.

Consider funny cartoons like Bob Montana and Vic Bloom’s Archie: They spearheaded the utilization of various outcry marks in ordinary discussions. A commonplace exchange would look something like this:

“You can watch me play!”

“However, I would prefer not to watch it! I need to play as well!”

What the shout focuses on is an essential degree of commitment, and that is their true mission when we send instant messages today.

At that point there are other etymological societies: Scandinavians were utilizing shout marks in a strikingly modern manner, even before Archie first showed up in 1941. In nations like Sweden, for instance, it’s for quite some time been regular to open a letter with “Sandra!” instead of the more stifled “Dear Sandra.”

Once more, that doesn’t flag incredible fervor to such an extent as mindfulness.

Chapter 6 – Realizing that words frequently merge and make new posterity causes us to comprehend Old English.

Words are somewhat similar to individuals. At times they’re attractively pulled in to one another. When they draw near, they wind up coupling and making new posterity.

In phonetics, these half and halves are called mixes.

Ordinary English is covered with instances of them: Take “sitcom” – a blend of “situation” and “parody.” Then there’s “motel,” the offspring of “motor hotel,” and “camcorder,” a cross among “camera” and “recorder.”

Mixes insert a language with ever-more prominent recurrence in the cutting edge world. Innovative systems like the worldwide online network permit them to sprawl forward and quicker. What starts as a web in-joke can before long enter the discourse of millions.

One genuine model is “staycation” – a stay-at-home excursion. It was begun by a columnist in the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1944 yet went untapped for the greater part of a century. When the 2008 monetary emergency began squeezing individuals’ discretionary cash flow, it returned. An ever-increasing number of individuals were doing the word’s description and it appreciated a resurgence.

Yet, because another word gets a foothold in a language, it doesn’t ensure that it’ll have a backbone. While some entries end as quickly as their beginnings, others stay in the language world for a long time.

“Chortle,” a mix of “chuckle” and “snort,” – instituted by Lewis Carroll in his 1856 story Alice in Wonderland – is one of those tough assortments. Yet, “cafetorium,” a coinage quickly utilized during the 1950s to portray huge corridors that could be utilized as both assembly rooms and cafeterias, scarcely held tight for 10 years.

Understanding how English mixes words aren’t simply of savant intrigue however – it can likewise assist us with understanding its past.

That is because Old English was a tremendous blunder.

For instance, refutation was a genuinely clear issue in Old English. You simply put “ne” before the word you were discrediting. So “I have” was “Ic haebbe” and “I don’t have” was “Ic ne haebbe.”

That prompted unending mixing. To state something as “I don’t have the cushion,” you expected to make a sentence like “I nave the pad.” For this situation, “nave” is a mix of “ne” and “have.” Likewise, if we despite everything utilized the rationale of Old English, we’d make statements like “nam” for “I’m not,” and “nis” rather than “it isn’t!”

Chapter 7 – How we stress the way to express words can likewise prompt etymological alteration.

If you see the great 1934 wrongdoing spine chiller The Thin Man, you’ll become aware of something awkward about how controller Nick Charles articulates a single word. In his grasp – or rather, mouth – the accentuation in “suspects” changes. While we state “suspects,” he says “suspects.”

So what’s happening here?

Indeed, a piece of the development of action words into things includes a move of complement. The pronunciation or the focused piece of a word changes.

If you use ‘’suspect’’ as an action word, you will understand this. It’s “to suspect,” isn’t that so? That alters when it’s become a thing – in this manner “the suspect.”

In the same way as other etymological changes, the development of this new thing took some time. At the point when The Thin Man was delivered during the 1930s, the word was part of the way through its advancement. That is the reason Charles articulated it how he did.

This is a case of the retrogressive move of complement that goes with the development of new things. It’s an overall guideline in English. Consider “rebels” a thing versus “rebel” as an action word. Or then again the way that wrongdoings are “recorded” to make a “record.”

Changes in elocution likewise become possibly the most important factor once new words are framed out of two more established words: a “black board,” for instance, is a board that has been painted dark. A “blackboard,” then again, is a record connected to schoolroom dividers.

If you state the words for all to hear, you will notice that something fascinating happens to the complement. A “slate” is the first term. In any case, with regards to the new expression, the accentuation has moved – henceforth “writing board.” The retrogressive move mirrors the way that something more explicit than the entirety of its parts is being alluded to.

The equivalent goes for “blackbird” instead of a “black bird.” The previous is the name of a particular sort of fowl, while the last can be utilized to allude to a fledgling that happens to have dark plumes, for example, a crow or a raven.

Chapter 8 – “Like” has advanced since its commencement, and contemporary utilization is only the most recent alteration.

In this book summary, we’ve seen that languages alter – a lotl! They advance and adjust after some time as opposed to staying fixed. Consider the contrast between a film and a photo.

One late alteration in the manner individuals communicate in English is genuinely famous: how they utilize “like.”

In any case, regardless of all the hubbub, “like” is a word that has never stayed the same for a long time. English speakers have been adjusting their utilization since it previously showed up in their vocabularies.

The world’s causes can be followed back to Old English when its spelling was “lic.” Derived from “gelic” – signifying “with the body of” – it was a wordy method of saying that something looked like something else. As it were, that it was “like” something different.

When it had been degraded to a solitary syllable, it began being consumed by different words. Now and then it was essentially gulped down, making it difficult to spot today.

Look at the qualifier “slowly:” What on earth does that have to do with “like?”

At first, Old English speakers said something was “slow-like” when they needed to portray the pace at which it was moving. In the long run, “like” was decreased to a considerably shorter postfix – “ly.” And once that had occurred, it began joining itself to a wide range of descriptors. That is from where we get words like “angrily,” “portly” and “saintly.”

So it’s a word that is constantly being taken on new jobs – how it’s pre-owned today is only the most recent.

In any case, what precisely does that involve?

Recall emojis and words, for example, “well” and “totally.” As we saw, they add feelings to messages and communicate in the language. “Like” is somewhat, well, that way. It assists speakers with passing on their feeling of something.

For instance, a youngster depicts a trip to a companion: “So,” she says, “there we were and there were, similar to, grandmas and granddads, and, as, grandchildren and cousins all processing about.”

“Like” isn’t the simple filler that it’s occasionally described. What it permits this speaker to do is express to her unexpectedly that there were heaps of individuals in a spot she didn’t anticipate that they should be. It causes to notice the way that she thoroughly considers it normal to locate an entire family in the area she’s discussing.

Also, that makes it a valuable expansion to English!

Words on the Move: Why English Won’t—and Can’t—Sit Still (Like, Literally) by John McWhorter Book Review

The one consistent throughout the entire existence of the English language is changed. From elocution to accentuation, English has altered significantly throughout the long term. In any case, when you look closely, you’ll notice before long notification that some modern spasms have profound roots.

Newcomers to the language like emojis and difficult-to-nail down words, for example, “like” mirror the way that language has been the essential mode of communicating feelings for longer than craftsmanship.